For the flock

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T his book and the experiences that it describes could never have happened without the help and encouragement of many people. Id like to thank John Aikin, Howard Ashlock, James Attwood, Adah Bakalinsky, Jane Bay, Cheryl Bentley, Brinley Best, Joe Bishop and Lisa Leonard, Patrick Brennan, Roberto Bruno, Patricia Cady, Chris Carlsson, Kathleen Carr, Jeffery Chinn and Mary Nelson, Kyle Chiu, Jacquelyne Cordes, Gerry Crowley, Richard Cuneo, Hank Donat, Art and Marshall Dong, Dorothy Dong, Tom Eby and Denise St. Onge, Barry Edghill, Peggy Ensminger, Sybil Erden, Jann Eyrich, Joe Fields, Chuck Galvin, Kimball Garrett, Leigh-Ann Gerow, Jamie Gilardi, Loretta Giuliotti, Victoire Grassl, Maria Groppi, Larry Habegger, Shawn Hall, Gayle Hampton-Smith, Alan Hopkins, David Kennedy, A. T. Kippes, Ross Lai, Lori Lancaster, Susan Leahy, Mark Leno, Laura Lent, Laurie Leonard, Dave Long, Nate and Betsy Lott, Ben Margot, Margo Metegrano, Howard Munson, Barbara Oplinger, Peter Overmire, Sylvia Portillo, Mike Radke, Allan Ridley, Sark, Ed and Shirley Schaffnit, Richard Schulke, Louis Silcox, Jim Stevens, Gary Thompson, Laurel Wroten, Edna Yarbrough, Paul Yglesias, Jamie Yorck, Pattie Yost, and the officers and members of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers.

Special thanks go out to my father, Clyde Bittner; my mother, Jenny Bobst, who, regrettably, did not live to see completion of the book; my sister, Beth Lyons; and to Daniela Cossali and Natalie Cooper.

For help in getting the manuscript ready for publication, I want to thank the publisher of Harmony Books, Shaye Areheart; my editor, Teryn Johnson; my agent, Candice Fuhrman, and her associate, Elsa Hurley; readers Gardner Haskell, Berenice Jolliver, Irvin Jolliver, and Linette Jolliver; and my copy editor, Jim Gullickson.

My biggest thank-you goes to Judy Irving, who has read, without complaint, every revision of this manuscript, made corrections and suggestions, and listened to me patiently when I was just thinking out loud.

To those Ive forgotten, my sincere apologies.

CONTENTS

Introduction

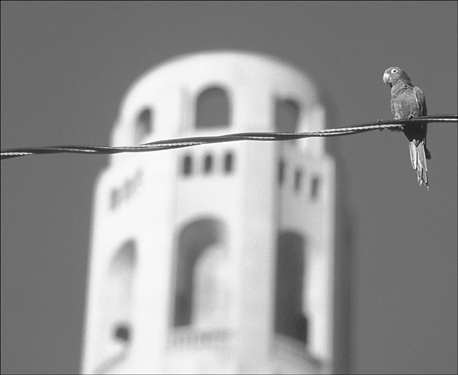

I m standing on the front deck of an old cottage on San Franciscos Telegraph Hill. The cottage, vine-covered and frail, is nestled within the immense and chaotically lush gardens that tumble down the hills steep eastern face. Just to my right is a large cage containing three lime-green parrots with cherry-red heads. On top of the cage, another parrot prowls at liberty. In my left hand, Im holding a cup filled with sunflower seeds. Clinging to the cups rim are two more parrots who are making quick and expert work of the seeds. There are parrots on my right hand, on my shoulders, and on my head.

In front of me, on the limbs of a tall shrub, are another dozen or so. They watch me with eager eyes as I pass around a handful of seeds. One of them, determined to get my attention, flaps his wings furiously, causing the thin branch hes perched on to bounce up and down. Five more parrots eat from a small pile of seeds on the deck railing. To my far right, a gang of fifteen crowds around a large, seed-filled dish that sits on the thick growth of ivy climbing over the railing corner. Another ten sit on the power lines above me. In all, Im surrounded by more than fifty parrots.

The birds on the lines start up an insistent, staccato squawking that grows louder and more anxious as those below gradually join in. A group of tourists, their faces lit with fascination, stop to stare. The squawking is getting so loud that one of the tourists has to shout his question.

Dont you ever lose any?

Theyre not mine, I shout back, laughing. Theyre wild.

Wild? Are you serious? Wild parrots in San Francisco?

Before I can answer, the screaming hits a tremendous peak, and the entire flock bolts. In the scramble to leave, a few of the birds nearly collide with the startled, ducking tourists. The parrots continue to scream as they fly on stiff, frantic wings through a gap in a row of trees and disappear from view.

Yes. Wild parrots in San Francisco.

A Rolling Stone

T he first time I saw them was on Russian Hill at a housecleaning job. I was on my knees, dusting an end table, when I noticed four brightly colored birds clinging to a small feeder that hung just outside the living room window. At first glance, I didnt know what I was looking at. Then it dawned on me: They were parrots. The birds must have sensed my excitement, for they immediately fled. I jumped to my feet and ran to the window, but the only trace of them that remained was the swinging feeder.

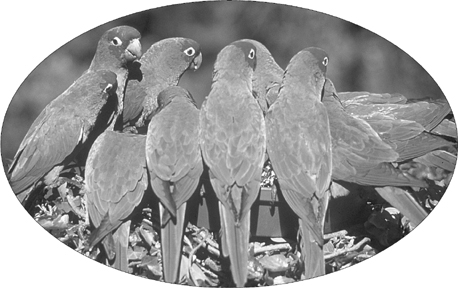

A few weeks later, I was astonished to see the same four birds again, this time in a tree that grew just outside the place where I was staying on Telegraph Hill. They were crawling around the trees bushy limbs and eating its tiny cones. Completely bewildered, I walked as close to them as they would allow. Id never known much about birds, so the parrots raised questions that I had no idea how to answer: How had they gotten to San Francisco? Were they someones pets? What species were they? How could they stand the cold? The last question puzzled me most. San Franciscos weather is generally moderate year-round, but I assumed that anything less than a hothouse environment would kill a tropical bird. Maybe they werent parrots. Id always thought of parrots as large birds, but these were only about a foot long, nearly half of which was their tail. They did have the bright colors of a parrot, thoughgreen, with a red head, and red patches on the shoulders of their wingsand like parrots, they had hooked beaks, which were comically large. Their eyes were so expressive that even from a distance the birds struck me as personable and intelligent. There was something goofy about their eyes. It was as if they concealed the punch line to some joke.

All of a sudden, I saw their good humor vanish. They stopped eating and began scanning the area with eyes that now bulged in alarm. They pulled their feathers in tight against their bodies and their breathing became labored. One of the four uttered a few low squawks, and they all took off in a noisy and sloppy panic. I looked around the garden, but I didnt see anything that I thought should have frightened them.

Over the next few weeks, the four parrots continued to pass through my neighborhood. Because they squawked constantly in flight, I always knew when they were coming. The moment I heard them, I dropped whatever I was doing and ran outside to watch. They were different from other birdsso different that it was difficult to think of them as birds at all. They seemed more like monkeys. Sometimes theyd perch on the power lines and, for no apparent reason, scream like lunatics. They also liked to hang upside down. Occasionally Id see two of them dangling side by side and shrieking hysterically while trying to bite each other in the face.

I learned later that the parrots were visiting my neighborhood because of the many trees that grew there. I didnt know trees any better than I did birds, so I asked Helen Arpin, the woman who lived on the floor above me, the name of the tree from which Id seen them eating. She said it was a juniper. There was another tree that the parrots liked even more, an Asian fruit tree called the loquat. I already knew the loquat. When the parrots werent eating its fruit, they often napped in it. Loquat leaves are broad and long, nearly as long as the parrots. The birds feathers and the trees leaves were similar enough in color that when the birds perched on the inner branches, they were almost perfectly camouflaged. Even when I knew for certain they were in there, they could be difficult to spot. Eventually, theyd pop their bright red heads out of the treetop, and Id have them in sight again.