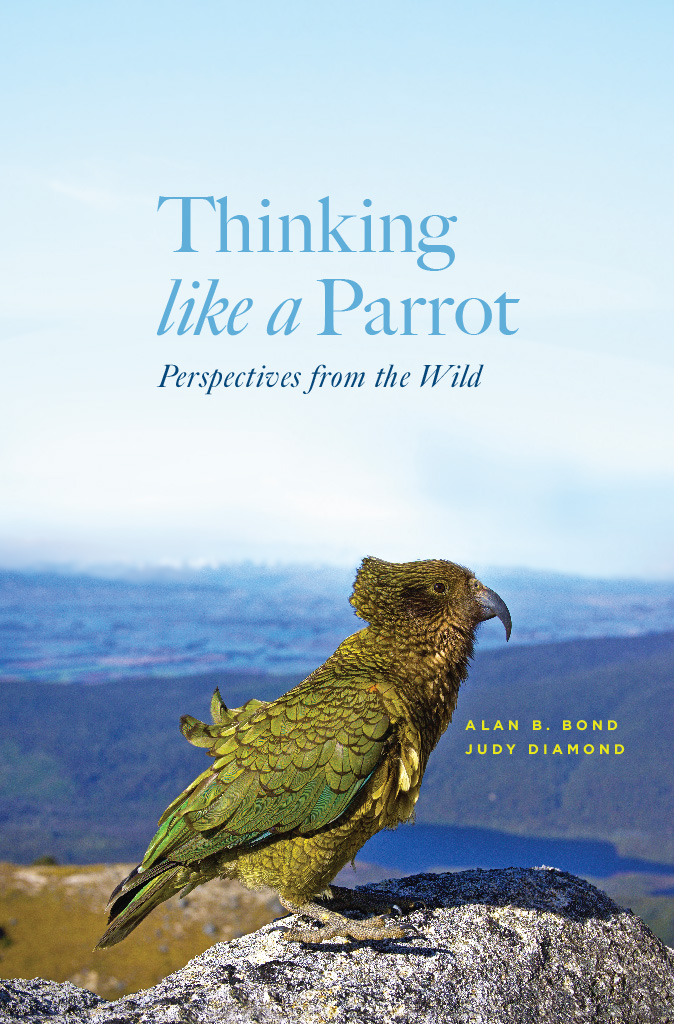

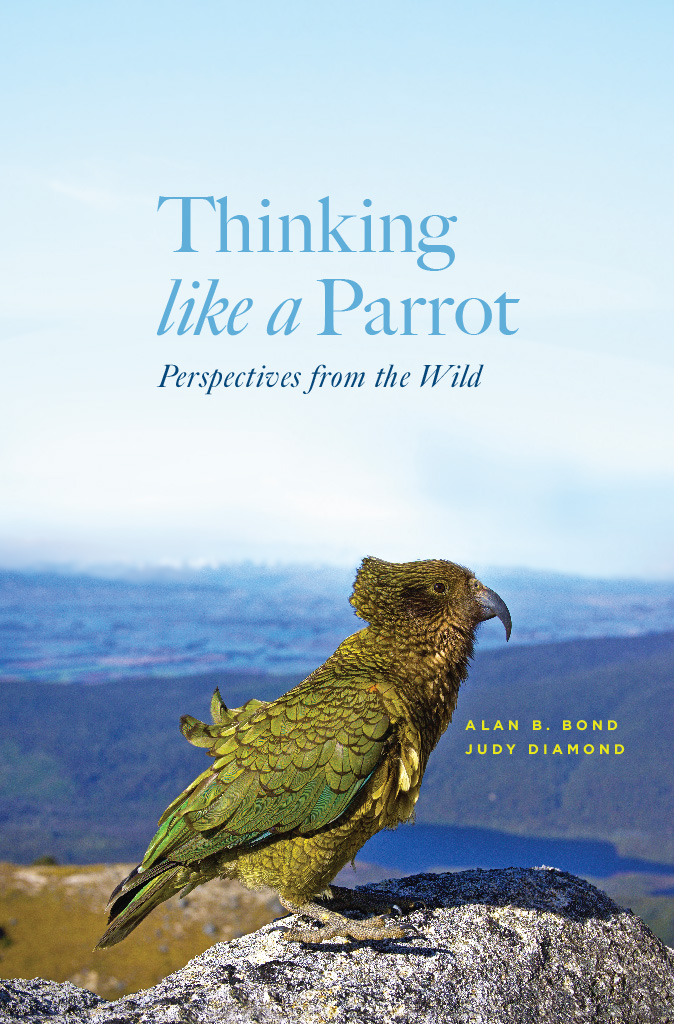

THINKING LIKE A PARROT

...

THINKING

LIKE A

PARROT

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WILD

...

Alan B. Bond and Judy Diamond

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24878-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24881-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226248813.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bond, Alan B., 1946 author. | Diamond, Judy, author.

Title: Thinking like a parrot : perspectives from the wild / Alan B. Bond and Judy Diamond.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018058791 | ISBN 9780226248783 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226248813 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Parrots. | ParrotsBehavior. | Cognition in animals. | Emotions in animals. | Social behavior in animals.

Classification: LCC QL696.P7 B74 2019 | DDC 598.7/1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018058791

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of

Ann and Bernard Diamond

Charlotte and Alan Bond Sr.

Contents

Common and Scientific Names of Parrot Species Mentioned in the Text

Analysis Methods for Brain Volume and Body Mass in Parrots and Corvids

Comparisons of Form and Frequency of Play Behavior in Keas, Kks, and Kkps

Kea Social Network Analysis

Kea Vocalizations

Kk Vocalizations and Dialect Methods

Conservation Status of Parrot Species Mentioned in the Text

Parrots are intriguing creaturesdistinctive, amusing, and curious. In nature, they are linked through webs of interaction with the flora and fauna of the Southern Hemisphere. From their original ranges, some parrots have spread across the globe, settling in new areas with their human neighbors, while others have been devastated by poaching, capture, and the destruction of their forest habitats. Thirty years ago, we set out to understand what drives the ecological and behavioral adaptability of parrots, and we initially focused on keas, known for their inventive and often reckless behavior in the high mountains of New Zealand.

New Zealand has long since closed its high country garbage dumps, which pose a danger to both wild and domestic animals and pollute nearby water sources. But at the time we began our work, one particular site provided refuse disposal for the residents of the alpine village of Arthurs Pass and incidentally served as a focus for an established community of keas. The parrots had been visiting the place regularly for much of the latter half of the twentieth century. In 1986, we spent our honeymoon at the dump, which ultimately led to a series of field studies and an extended monograph on this, the worlds only alpine parrot.

New Zealands high mountains provide lean pickings for hungry parrots, and keas are expert at making do with whatever is available. They dig out grubs under lichen-encrusted boulders and take buds, leaves, or fruits from mountain beech trees, depending on the current season. In spring, they eat mountain daisies, consuming flowers, roots, and sometimes the entire plant. In summer, they catch grasshoppers and chew the nectar-filled flowers of New Zealand flax. In fall, they feast on abundant alpine berries, particularly those of the snow totara. Winter is the starving season, when being opportunistic and open-minded is essential for survival. The presence of the dump throughout the year must have seemed to the keas like a self-replenishing candy store.

It rained at the field site nearly every day, and clouds of bloodthirsty blackflies tormented both us and the birds. At times, we arrived before dawn to find the trash burning, with acrid smoke saturating the air. Still, the area had its own special beauty. Alongside the dump tumbled the Bealey River, a tributary of the great meandering Waimakariri. From one hour to the next, the river could transform from a gentle stream to an angry torrent, abruptly gaining two meters in depth before it settled back down. Surrounding us were stands of native mountain beech, remnants of great Gondwanaland forests that once spread across the Southern Hemisphere. These trees shaded pillows of moss-covered rocks and soil; bright yellow and blue lupines, introduced by early English settlers, sprouted around the edges of the dump.

In the nineteenth century, ranchers brought sheep farming to New Zealands high country. In the absence of native predators, the sheep were turned out to wander unsupervised over open ranges for the winter. But ranchers did not reckon on opportunistic parrots. Keas had probably been attracted to carrion even in ancient times, when moa carcasses littered the landscape. The transition from feeding on carcasses to harassing docile live animals extended their creative foraging practices. A kea could alight on the sheeps back, dig into the soft flesh around the kidneys, and fly off with a beak full of suet. Invariably, this new source of nourishment began to support a larger population of parrots than could be sustained by beech fruits, grubs, and daisies. When the wounds that keas inflicted on the sheep became infected and the livestock began to die, ranchers took notice, and soon bounties were offered for the parrots. It took almost a centuryand new medical treatments to prevent wound infectionsfor ranchers and keas to make their peace. Even today, when keas harass sheep or damage ski resorts, the birds are captured and transplanted to more remote South Island locations.

A national park was established at Arthurs Pass in 1929, and the local railroad station eventually expanded into a thriving village, serving not only seasonal trampers and tour buses but also educational programs from schools throughout the South Island. The plentiful leftovers from these visitors soon became staples for hungry alpine parrots. We watched aggressive adult males expertly tear open blue garbage bags, showing us their preferences among the varieties of human foods. Sometimes the remnants of an entire deer carcass made its way to the dump, and the keas spent days industriously scraping the sinews from the bones.

In successive seasons, we returned with funding from the National Geographic Society. In collaboration with New Zealand researchers, we banded individual keas as they visited the dump. We recorded details of the birds behavior, noting their foraging and social interactions, and gradually learned to distinguish their individual personalities. Adult female keas

Over the years, we expanded our studies to investigate the dynamics of kea vocal communication throughout their entire South Island range, and we brought our two young children with us into the field. Each family member had a job to do: Our daughter, Rachel, recorded GPS locations, while our son, Benjamin, photographed the birds. While we observed and recorded the keas, the kids worked on homework that they emailed back to their Nebraska classrooms. Our analyses revealed the vocalizations keas used, the functions the calls served, and how they varied from one part of their range to another. We also discovered that juvenile keas had characteristic calls that were distinguishable from those of adults. Juvenile keas were beginning to seem like human teenagers, with their own ways of communicating with each other that excluded older generations.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).