Volume compilation, chronology, and notes copyright 2010 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced commercially

by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices

without the permission of the publisher.

www.loa.org

Reading Pictures and accompanying artwork

copyright 2010 by Art Spiegelman.

Gods Man copyright 1929, 1957;

Madmans Drum copyright 1930, 1958;

Wild Pilgrimage copyright 1932, 1960 by Lynd Ward.

Essays copyright 1974 by Lynd Ward.

Published by arrangement with

Robin Ward Savage and Nanda Weedon Ward.

The endpapers are adapted from a design created by

Lynd Ward for the binding boards of Prelude to a Million Years

(New York: Equinox Cooperative Press, 1933).

Distributed to the trade in the United States

by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

and in Canada by Penguin Group Canada Ltd.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010924275

e ISBN : 978-1-59853-396-5

First Printing

The Library of America210

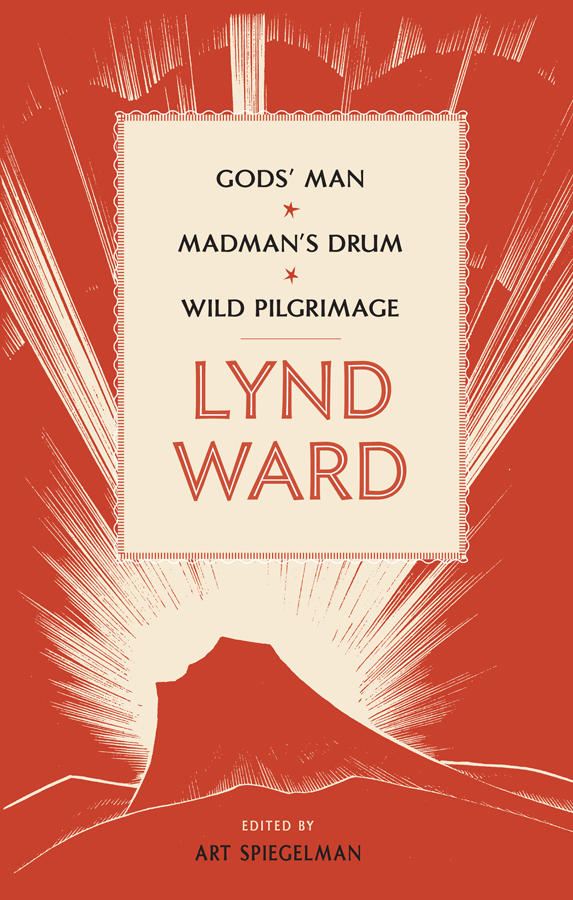

Lynd Ward: Gods Man,

Madmans Drum, Wild Pilgrimage

is published with a gift in honor of

MARJORIE J. BERKLEY

CONTENTS

by Art Spiegelman

READING PICTURES

A FEW THOUSAND WORDS ON SIX BOOKS WITHOUT ANY

YND WARD MADE BOOKS . He had an abiding reverence for the book as an object. He understood its anatomy, respected every aspect of its production, intimately knew its history, and loved its potential to engage with an audience. This is one of the reasons he commands our attention now, when the book as an object seems under siege.

YND WARD MADE BOOKS . He had an abiding reverence for the book as an object. He understood its anatomy, respected every aspect of its production, intimately knew its history, and loved its potential to engage with an audience. This is one of the reasons he commands our attention now, when the book as an object seems under siege.

He was born into a devout Methodist family in Chicago, in 1905. His father, Harry Frederick Ward, a progressive minister, imbued him with the social conscience and activism, as well as the pronounced Protestant work ethic, that informed his work and life. (In 1920 his father became the first chairman of the ACLU, and in the 1950s he was blacklisted for his prominence in the Popular Front.) As a tubercular child, Lynd Ward pored over Gustave Dors nineteenth-century Bible illustrations since his father forbade anything as profane as the Sunday funnies in their home. Denied a comic-strip vocabulary, Ward would grow up to help define a whole other syntax for visual storytelling.

Right after graduating from the Teachers College of Columbia University, Ward took off for a year of advanced study in Europe with his new bride, future author May McNeer. Fortunately for those who cherish his lifework, they ended up in Weimar Germany rather than in Paris. Instead of pursuing the formalist Modernism in the air on the Left Bank, he entered the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, became steeped in German Expressionist art, and learned wood engraving from a German master.

Ward happened onto a copy of Die Sonne, an antic, free-associative story of a modern Icarus told in a book of sixty-three woodcuts by Frans Masereel. Exuberantly whacking into wood in high expressionist mode, the Flemish artist invented the woodcut novel, inspired Ward, and continues to inspire artists today, myself gratefully included. First published in a popular edition the year before Ward got to Germany, Die Sonne (the third of more than fifty such works made by Masereel over his lifetime) had an introduction by Carl Georg Heise, a champion of what came to be known a decade later as Degenerate Art. Knowing only rudimentary German as a student in Leipzig, Ward couldnt have understood the introduction but must have savored Masereels power to communicate past national and linguistic barriers.

Communication was central to Wards developing aesthetic. In a 1949 essay for The Horn Book, looking back on the evolution of the book artist over the past twenty-five years, he noted that

the book artists fundamental problem involved a greater emphasis on art as communication. Curiously enough, this took place at a time when the field of painting gave rise to overriding tendencies towards abstract and esoteric expression.... It may very well be that what we see here is the separation of two elements that have always been present in the visual artsthe concern with communication and the concern with visual qualities that just are, and are their own justification for being. In the minds of many... the present trend towards concern with formal qualities is inevitable and desirable. On the other hand, it can be contended that a balance between formal qualities in visual expression and concern with having something to say has resulted in some of the greatest visual statements of the pastHogarth, Blake, Daumier, Goya, Callot, to name a few....

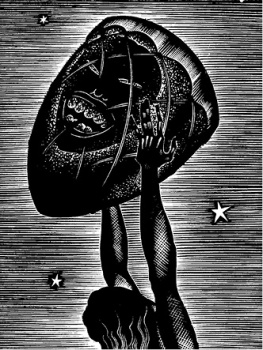

In 1929, after Ward returned to New York and became a struggling freelance illustrator, he discovered Destiny, a German wordless novel by Otto Nckel. Nckels sole work in the form followed Masereels example, but with a more cinematic narrative flow, presenting a highly coherent, vehemently melodramatic tale of a prostitutes life and death in luminous and painterly lead engravings. Destiny struck the twenty-four-year-old Ward hard, galvanizing him to produce the 139 narrative wood engravings that became Gods Man later that same year. It was an immediate success. (Released in October 1929, in the same week as the stock-market crash that ushered in the Great Depression, it went on to sell over twenty thousand copies in the next four years.) Gods Man introduced the woodcut novel and Lynd Ward to America and still remains the most emblematic and popular of his six published books in this genre.

Gods Man is also emblematic in an almost medieval sense, with its stark symbolism and its black-and-white depictions of good and evil on a Faustian theme. Our Hero, a destitute artist seeking fame and fortune, accepts a magic brush from a Mysterious Stranger. His rapid rise proves hollow, but he flees the corrupt City, meets a beautiful goatherd, and lives a life of Edenic beatitude until the Mysterious Stranger comes to collect payment and Our Hero dies. Despite the polytheistic implications of the oddly positioned apostrophe in its title, Gods Man is a cautionary tale about the Sin of Pride.

The visual style of this first book, inflected by the Moderne streamlining of Rockwell Kentas well as by the Expressionist films of Murnau and Langveers away from the gestural Modernism that informs Masereel and Nckel but looks back instead to medieval book artists and to classical woodcut masters from Albrecht Drer to Thomas Bewick, a symptom of Wards temperamental predisposition toward craftsmanship.

Filled with the earnest Sturm und Drang of a very young man, Wards first novel had enough of an impact on Susan Sontag thirty-five years later to make her shortlist of canonical Camp works in her influential Notes on Camp. Its a dubious distinction, although her essay does include the admonition that Not only is Camp not necessarily bad art, but some art which can be approached as Camp (example: the major films of Louis Feuillade) merits the most serious admiration and study. Some of Wards images are unintentionally risible (the depiction of Our Hero idyllically skipping through the glen with the Wife and their child makes me snicker), but others (the two plates of Our Hero in the desolate canyons of the City after fleeing from the Mistress come to mind) are indelible, demonstrating his formidable powers of graphic composition.

YND WARD MADE BOOKS . He had an abiding reverence for the book as an object. He understood its anatomy, respected every aspect of its production, intimately knew its history, and loved its potential to engage with an audience. This is one of the reasons he commands our attention now, when the book as an object seems under siege.

YND WARD MADE BOOKS . He had an abiding reverence for the book as an object. He understood its anatomy, respected every aspect of its production, intimately knew its history, and loved its potential to engage with an audience. This is one of the reasons he commands our attention now, when the book as an object seems under siege.