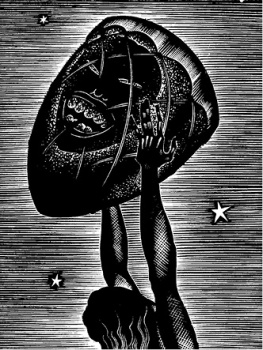

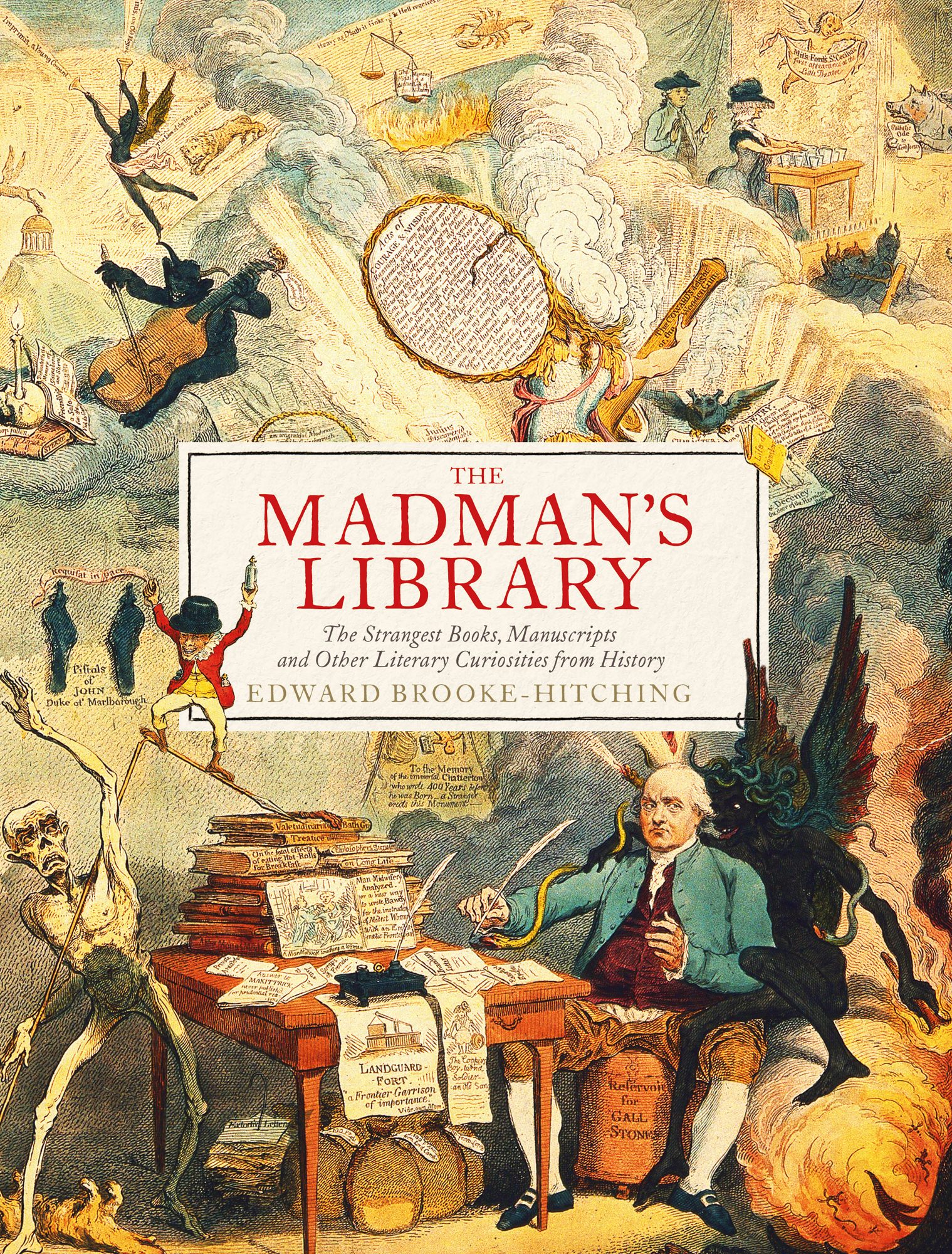

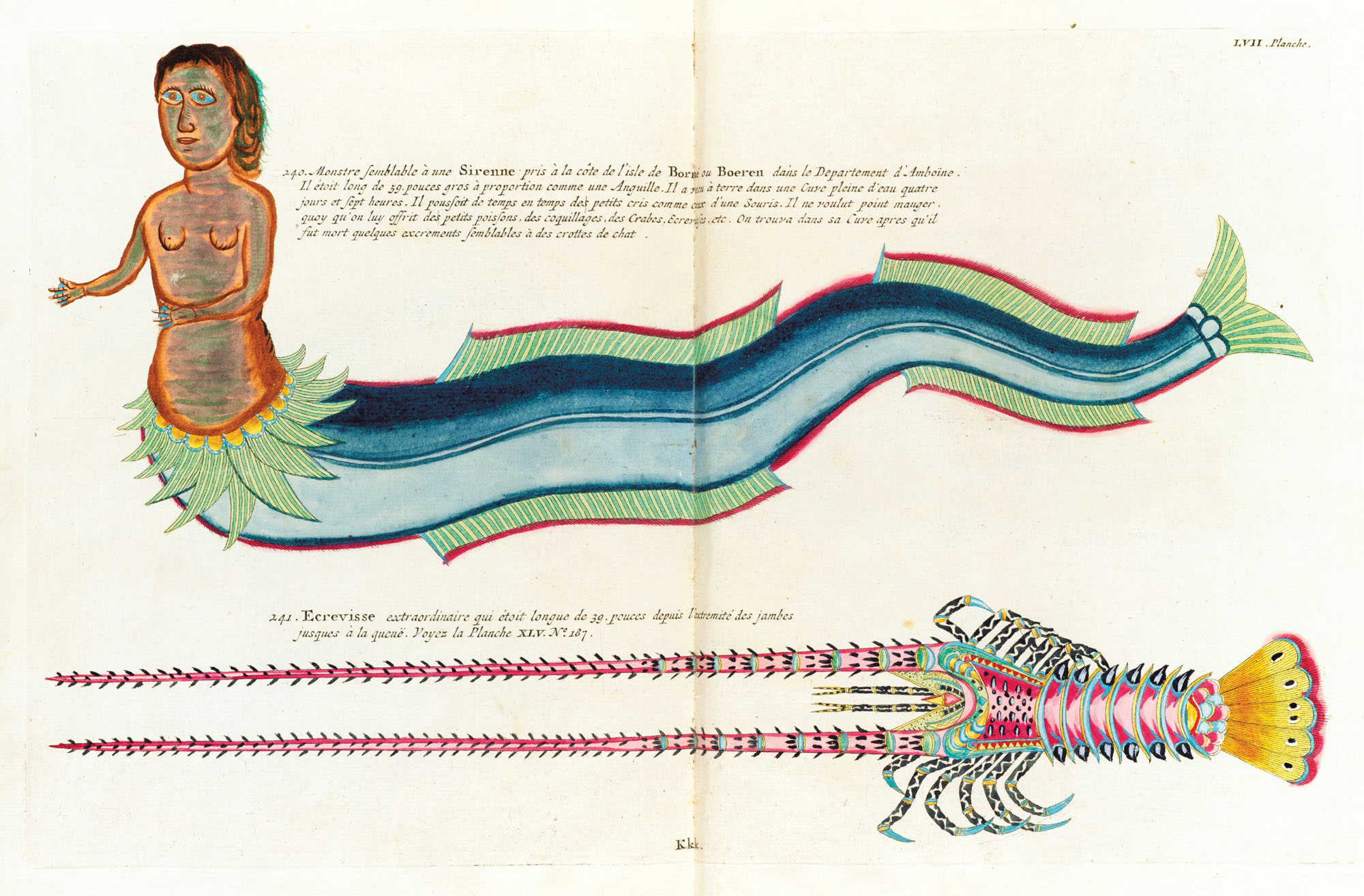

Illustration from a mysterious supernatural manuscript of c. 1775 in the collection of Londons Wellcome Library, known as the Compendium of Demonology and Magic (see for more).

INTRODUCTION

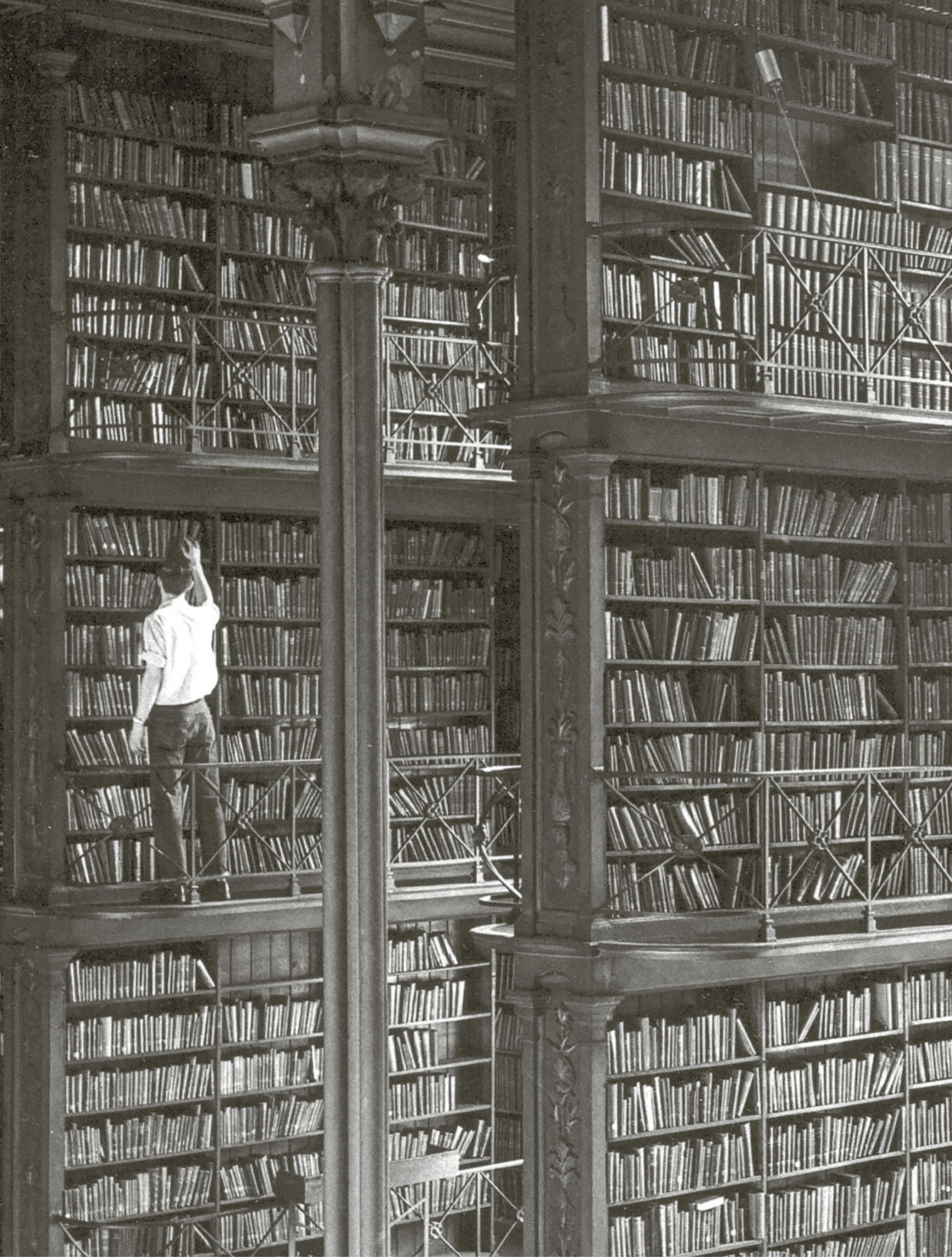

Books are lighthouses erected in the great sea of time.

Edwin Percy Whipple

I had just turned one when my father first used me as a bidders paddle at auction. With an antiquarian book dealer for a parent, home is a house built from books figuratively, and structurally. Every square inch of wall space is rigged with shelves groaning with leather bindings of radiant colours: rich red morocco (goatskin), white vellum (fine calfskin), naval blues, jungle greens, solid golds and older, moodier antique browns, all glittering with varied degrees of gilt tooling.

The books breathe, too, exhaling a perfume of aged papers and leathers, the smell of centuries, varying just perceptibly by place and era of origin. The romance of this atmosphere is, of course, entirely lost on a child. At least, initially. By the age of ten I couldnt imagine there being anything less interesting in all existence than old books. By eighteen I found myself working at a London auctioneering company, spending every hour in their company; and by twenty-five, now hopelessly in love, I was siphoning funds away from comparative inessentials like food and rent to fill the few shelves of my own. (I have known men to hazard their fortunes, wrote the great American rare-book dealer A. S. W. Rosenbach in 1927, go long journeys halfway about the world, forget friendships, even lie, cheat, and steal, all for the gain of a book.)

At around the same time, across the Atlantic a team at Google were completing a calculation that no one had ever dared attempt. The Google Books initiative, codenamed Project Ocean, had been secretly launched eight years earlier, in 2002, with the remit to source and digitize a copy of every printed book in existence. In order to do this, the team members determined that theyd need some idea of just how many books this would involve. And so they amassed every record they could find from the Library of the United States Congress, WorldCat and various other global cataloguing systems, until they reached a billion-plus figure. Algorithms then whittled this number down, removing duplicate editions, microfiches, maps, videos and one meat thermometer added to a library card as an April Fools Day joke long before. Finally, they reached an approximate total of every book available. There were, they announced, 129,864,880 existing titles and they intended to scan them all.

This number, of course, expands exponentially when considering all the lost works of history, worn away by use, swallowed up by natural disasters (Shakespeares Third Folio is actually rarer than the First, because the bulk were destroyed with the rest of booksellers stock in the Great Fire of London in 1666), and, of course, deliberate destruction whether from burning in great pyres (sometimes accompanied by their authors), or even, in the case of 2.5 million Mills & Boon novels in 2003, shredded and mixed into the foundations of a 16-mile stretch of Englands M6 toll road to help bind the asphalt. The British politician Augustine Birrell (18501933) found Hannah Mores works so boring that he buried the complete nineteen-volume set in his garden. Sometimes, in acts of bibliophagia, literature has been literally devoured: the engraved oracle bones (see

Within that figure of 129,864,880 books are all the great classics of literature that survive today continually studied, reprinted and retold, and the focus of past literary histories. But as the Google choice of codename Project Ocean illustrates, these famous works are, of course, mere droplets in an ancient, endless literary sea. The books I have always been interested in finding are the sunken gems twinkling in the gloom of this giant remainder, the oddities abandoned to obscurity, too strange for categorization yet proving to be even more intriguing than their celebrated kin. Which books, I wondered, would inhabit the shelves of the greatest library of literary curiosities, put together by a collector unhindered by space, time and budget? And what if these books have more to teach us about the men and women who wrote them, and their periods of provenance, than might be expected?

The first problem one faces is the question of what exactly constitutes a curiosity. To an extent the idea is, of course, subjective: strangeness is in the eye of the book-holder. But after nearly a decade of searching through catalogues of libraries, auction houses and antiquarian book dealers around the world, following leads and half-remembered anecdotes, works of undeniable peculiarity leapt out. Each has a great story not just inside it but behind it, and as the books gathered, themes gradually emerged and the uncategorizable began to fall into the bespoke genres that form the chapters herein. Books Made of Flesh and Blood, for example, examines the history of anthropodermic bibliopegy (books bound in human skin) and other bizarre bodily means of book production. These practices are not as antiquated as one might think. Take a modern case like the Blood Quran of Saddam Hussein (), a 605-page copy of the holy book commissioned by the Iraqi dictator in 2000, written over a period of two years using 50 pints of his own blood.

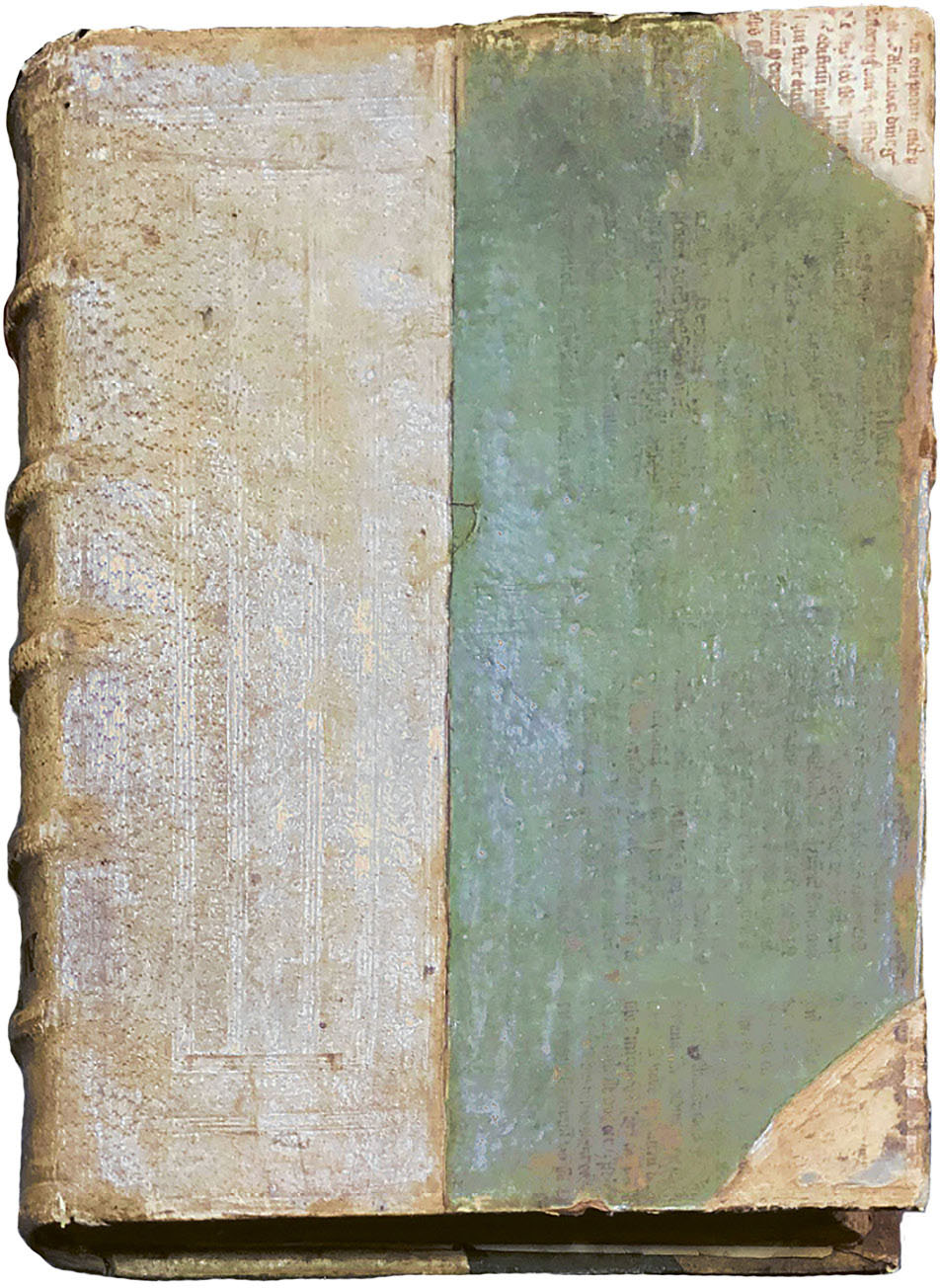

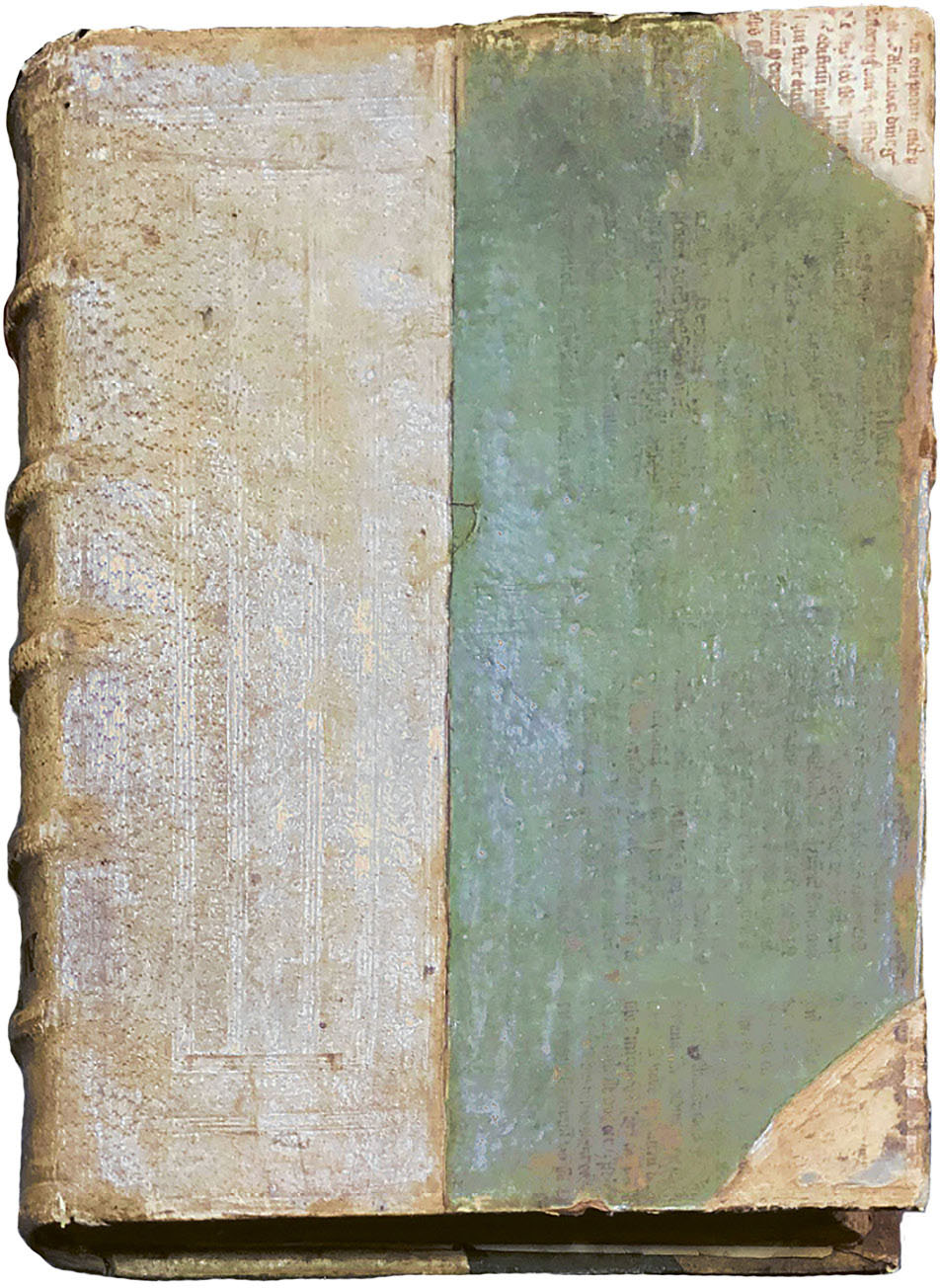

The dangers of handling arsenic-covered items including book bindings, from the periodical Annales dhygine publique et de mdecine lgale (1859). Artists who applied the paint would often poison themselves by licking the tip of their brush to get a fine tip.

A lethal seventeenth-century binding. The green paint is rich in arsenic, added by binders to hide their cost-cutting use of old manuscript vellum for the boards (and later, as pest control). Its thought that many such deadly bindings lie unidentified in collections around the world.