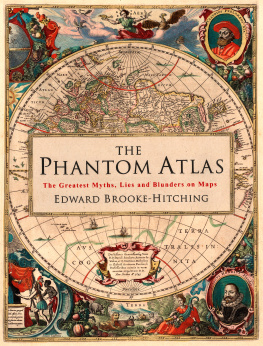

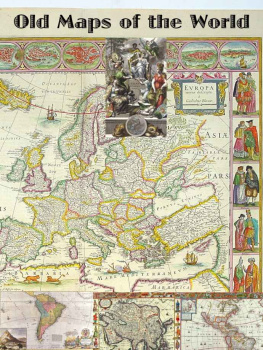

Pieter Gooss grand Nieuwe Werelt kaert, 1672.

Americae Sive Qvartae Orbis Partis Nova Et Exactissima Descriptio, by Diego Gutirrez (1562).

INTRODUCTION

So Geographers in Afric-maps

With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps;

And oer uninhabitable Downs

Place Elephants for want of Towns.

Jonathan Swift

As the sun climbed the June sky, the vessel Justo Sierra cast off. Its mission: to scour the Gulf of Mexico for the elusive 31-sq. mile (80-sq. km) island known as Bermeja. The crew were following the guidance of, among others, the cartographer Alonso de Santa Cruz, who charted the island in his 1539 map El Yucatn e Islas Adyacentes ; and the more precise positioning provided by Alonso de Chaves in 1540, in which the writer described the land mass as blondish or reddish.

Finally, they reached the given coordinates and there they found nothing. Only open, unbroken water, as far as the eye could see. There was no trace of an island certified on countless navigational charts. The mariners were thorough and swept the area, taking extensive measurements and soundings, but to no avail. Bermeja, it turned out, was a phantom. Just like that, an established fact became fiction. But what is particularly surprising about this sixteenth-century ghost territory is the lifespan it enjoyed because the Justo Sierra wasnt a ship from antiquity the crew was a multidisciplinary team of scientists put together by the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The year was 2009.

This is an atlas of the world not as it ever existed, but as it was thought to be. The countries, islands, cities, mountains, rivers, continents and races collected in this book are all entirely fictitious; and yet each was for a time sometimes for centuries real. How? Because they existed on maps.

Historically, cartographic misconceptions have commonly been disregarded. Perhaps this is because, viewed as mere errors, there is a tendency to dismiss them as insubstantial. But one need only glance at, say, the charts confidently proclaiming California to be an island, the mysterious, black magnetic mountain of Rupes Nigra at the North Pole or the depictions of Patagonia as a region of 9ft (2.7m) giants to realize that these invented lands are crying out for exploration. How did these ideas come about? Why were they believed so widely? And how many other equally strange examples are there to find?

One might assume that these ghosts have little bearing today, but, as the story of Bermeja demonstrates, a fascinating characteristic of many of these misbeliefs is their remarkable durability. Indeed, there are those that survived into the nineteenth century and beyond: Sandy Island, for example, in the eastern Coral Sea, was first recorded by a whaling ship in 1876 and thenceforth marked on official charts for more than a century. It finally had its nonexistence established in November 2012 136 years after it was first sighted (and a whole seven years after Google Maps was launched). These phantoms were considered a plague on navigational charts, frequently leading ships astray on fruitless confirmation missions. It was only as the ocean highways grew busier, and global positioning more accurate, that the methodical purging of these anomalies increased in efficiency. In 1875, for example, no fewer than 123 nonexistent islands (marked E.D., or Existence Doubtful) were cleared from the British Royal Navys chart of the North Pacific.

But what caused the recording of these nonexistents in the first place? Naturally, the further back we go the more superstitions, classical mythology and careful adherence to religious dogma have a role to play. The complex mappae mundi of Medieval Europe, for example, of which the Hereford Mappa Mundi ( c. 1290) is the largest extant example, serve as giant curiosity cabinets of history and popular belief. These immense, intricate collages were for the benefit of visiting pilgrims unable to read. Usually Jerusalem-centric, the maps were more to illustrate the scale of Gods works, with transcription errors abounding, as well as depicting the more outrageous phenomena reported by Pliny, such as the Sciapodes a species of man said to exist in the land of Taprobana, who used their one giant foot to shade themselves from the midday sun.

Mirages and other visual phenomena have also proven instrumental in manifesting the immaterial on maps. At sea, formations of low clouds were mistaken for land so often that sailors took to referring to them as Dutch Capes. The Fata Morgana in particular is a complex form of superior mirage that, from a ships bow, appears as a band of territory on the horizon. The name gives some indication of how contemptuously, and fearfully, it was held by mariners: the term comes from the Italian for Morgan le Fay, the Arthurian trickster enchantress. Most often seen in polar regions, the optical illusion is a prolific culprit in the perpetration of false land sightings it is accused, for example, of being the implement of disaster in Baron von Tolls 1902 expedition to find Sannikov Land in the Arctic Ocean.

And then, of course, there is the honest error, which is usually rooted in educated guesses of wishful mapping or the limited ability of contemporary measurement systems. Coordinates were rough and imprecise, until John Harrisons invention of an accurate marine chronometer in the eighteenth century provided a long-sought solution to the problem of measuring longitude. Errors were copied, and discoveries even frequently remade. Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, for example, during an 1838 survey of the Tuamotos, discovered an island at 1544'S, 14436'W. He named it King Island, in honour of the lookout who had spotted it. It wasnt until later that it was learnt the island had, in fact, been sighted several years earlier, in 1835, by Captain Robert Fitzroy of the Beagle , and named Tairaro.

Sometimes, phantoms even appear out of sheer whimsy. In his Cosmography (1659), Peter Heylyn tells the story of Pedro Sarmientos capture by Sir Walter Raleigh, who subsequently interviewed the Spanish explorer about curious entries on his maps of the Strait of Magellan. Raleigh questioned his prisoner about one particular island, which seemed to offer potential tactical advantage. Sarmiento merrily replied:

that it was to be called the Painters Wifes Island, saying that, whilst the Painter drew that Map, his Wife sitting by, desired him to put in one Countrey for her, that she in her imagination might have an island of her own. His meaning was, that there was no such Island as the Map pretended. And I fear the Painters Wife hath many Islands and some Countreys too upon the Continent in our common Maps, which are not really to be found on the strictest search.

Also to blame are the low-down, dirty liars: those who make the calculated and committed decision to invent an entire island or country for dishonourable and self-serving purposes. The impostor George Psalmanazar, for example, was a Frenchman on a mission to hoodwink the eighteenth century. He pretended to be a resident of Formosa (Taiwan) in a deception of depth and detail that fooled many. His book, An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa , was filled almost entirely with fantastic details pulled straight from his fertile imagination.