When I follow the serried multitude of the stars in their circular course, my feet no longer touch the earth.

What do we know of the beginnings of the universe? Really it depends on who you ask. A modern cosmologist will, of course, talk of the Big Bang, a theory that originated in 1927 with a Belgian priest named George Lematre (see New Visions of the Universe: Einstein, Lematre and Hubble entry ), who posited the idea of there having been a cosmic egg or primeval atom from which the universe exploded into being. Billions of years ago all time, space and energy occupied a single infinitely dense, infinitely hot point known as the singularity. In a trillion-trillionth of a second, this burst into expansion with a Big Bang and the universe came into existence, eventually ballooning to its current size of c.93 billion light years in diameter.

) more than 2300 years ago for what could be greater evidence of the divine than the perfection of eternity?)

A ceremonial dancing coat used by the shaman of the Koryak people, an indigenous culture of the Russian Far East. The coat is made of tanned reindeer skin and embroidered with disks of varying size representing constellations, with the belt sewn around the waist symbolizing the Milky Way.

So what exactly do we know of the beginnings of the universe? It is our oldest point of curiosity, the reason why we find creation myths at the root of cultures the world over. In Chinese mythology there is the first living being, Pan-ku, a furry horned giant who emerged from a cosmic egg after a wait of 18,000 years. Pan-ku cleaved the eggs shell in two with his axe to form the heavens and earth, and then fell apart himself. His limbs formed the mountains, his blood the rivers, his breath the wind.

Stephen Hawking was fond of illustrating his lectures with the belief of the Kuba people of the Democratic Republic of Congo, whose origin myth features the creator god Mbombo, or Bumba, a giant standing alone in darkness and water, who suffered a stomach pain and vomited up the Sun, Moon and stars. The Sun burnt away the waters, revealing the land. Mbombo then threw up nine kinds of animals and, with a final retch, man.

Elsewhere, in Hungarian mythology the Milky Way is called The Road of Warriors, a pathway down which Csaba, the mythical son of Attila the Hun, will charge to the rescue should the Szkelys (ethnic Hungarians living in Transylvania) be threatened. And nearly 4000 years ago in the region of modern Iraq, the ancient Babylonians had the Enuma Elish epic (see The Ancient Babylonians ), which told of the universe resulting from a cosmic battle between monstrous primordial gods.

A fifteenth-century mandala (universal diagram) of the three-headed, four-armed Hevajra, enlightened being of Tibetan Buddhism, who appears here dancing with his consort Nair tmy between four spiritual gateways at the centre of the cosmos.

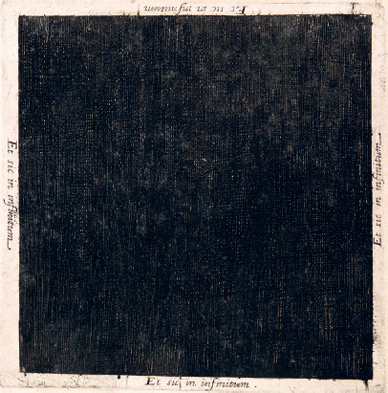

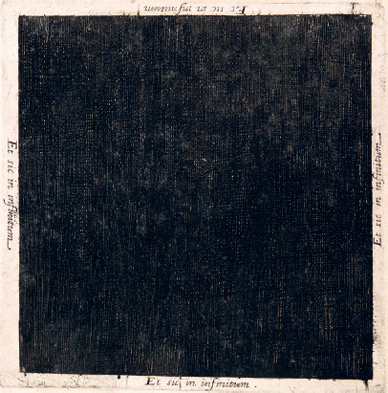

Consult the Bible (of which the Old Testament exhibits a clear influence from the Enuma Elish , with numerous also yielded an actual depiction of the pretemporal nothingness before the light of Creation, shown here by the physician and occultist Robert Fludd in his Utriusque cosmi (1617).

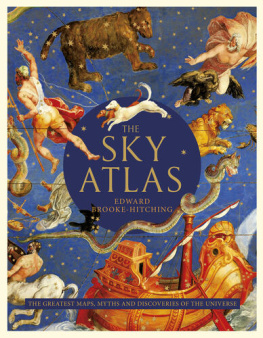

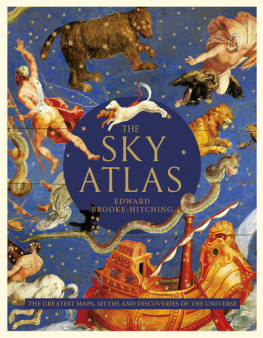

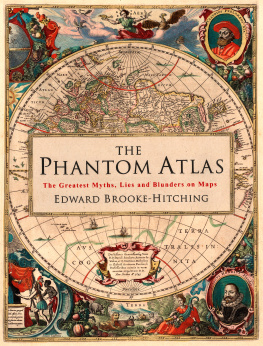

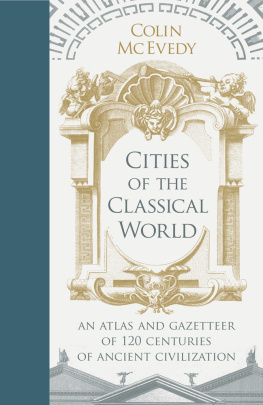

In fact, it was reflecting on this Fludd image of the black void of pre-Creation an image, one could argue, of the very first sky that prompted the idea for this book. In essence, the aim was to collate a visual history of the sky, condensing the extensive and intricate worldwide histories of celestial mythology, philosophical cosmology, together with the landmark discoveries of astronomy and astrophysics, into a single illustrated journey through the millennia. While there is a variety of paintings, instruments and photographs gathered on these pages to illustrate the chronology of our gradual decoding of the cosmic theatre, primarily this is an atlas of celestial cartography.

Robert Fludds image of infinity from his Utriusque cosmi , 1617.

To my mind, this is the most overlooked genre of mapmaking. In the history of cartography, reference works on the celestial map are vastly outnumbered by works focused on terrestrial cartography, despite the fact that the two genres were, traditionally, equally respected. Presumably this betrays an assumption that, while terrestrial maps portray the explorations and political machinations of monarchies and empires, maps of the world above reflect little of the world below. Indeed there can be a modern tendency to reduce star maps to the category of mere decorative material, with a perceived paucity of historical substance. (Certainly, this is not helped by their historical association with the pseudoscience of astrology.) Paradoxically they also suffer from a perception as lifeless technical diagrams of interest only to the student scientist. As we shall see, in response to both charges, nothing could be farther from the truth. Celestial maps are as vibrant with story as any other while often being peerless in their artistry.

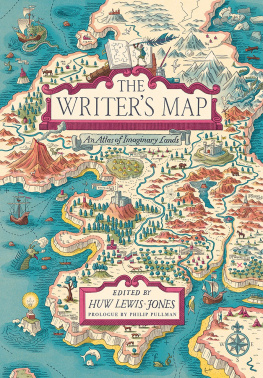

Of course, the mapping traditions of celestial and terrestrial cartography are as different as the manner of discovery they represent. Terrestrial mapping is rooted in the gradual process of active exploration. From our initial forays into the unknown world, blank on the page, we recorded and measured our geographic expansion step-by-step and ship-by-ship across the terrestrial plain. The grand pageantry of the heavens, on the other hand, was always on full glorious display from the very beginning. Against the countless visible stars, the Sun, Moon and wandering planets carried out their actions and phases openly, yet in total mystery.

To celestial cartographers, faced with such overwhelming vastness, the sky was itself a canvas for the projection of every myth, fear and religious fantasy in the mind of its observer, as the human brain searched restlessly for recognizable patterns in the chaos. With no vessels of exploration to probe this greatest of oceans, the astronomerartists could only draw on what they knew their gods, myths and animals and apply them to the constellations prominent in their order of brightness. Hence the twelve signs of the zodiac are older than written record, used by the ancient Romans, who inherited the concept from the Greeks. They, in turn, drew the idea from the Babylonians, and so on, back into the murk of prehistory.