CHARLEMAGNE

AND THE PALADINS

BY JULIA CRESSWELL

ILLUSTRATED BY MIGUEL COIMBRA

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

There was once a time, not too long ago, that stories about Charlemagne were as well-known as those about King Arthur. Why they have fallen out of fashion is a puzzle, because they are just as varied, interesting and exciting as those about Arthur and his knights. Perhaps we are uncomfortable because Charlemagne is a historical figure, and we dislike mixing fact and fiction. For many centuries the stories in this book were treated as historical fact. It was only in the 18th century that people began to seriously question the story presented by the legends. There are many inconsistencies and downright contradictions in the stories, and people must have begun to suspect that miracles did not happen quite as conveniently in real life as they did for Charlemagne in the legends.

There are over a thousand stories about Charlemagne and his paladins told in almost every Western European language, from Welsh, Irish, and Icelandic to Basque, French, and Latin. The greatest number is in German and, of course, French. The same basic stories were shared in many of the languages, but with each re-telling details and emphasis would change, subject to the creativity of the teller, so that a story at one end of the chain could differ considerably from that at the other. This process gives us an idea of how the stories developed. There is a core of truth underneath the main stories, which may be another reason that it took so long to disentangle fact and fiction. This process has been called mythistory, where fact and fiction feed into each other. A similar process can be seen at work in modern times, where stories of cowboys in the American West or of fighting in World War II, in both print and film, often blend fact and fiction. In the case of Charlemagne and his paladins, the stories arose in a time when written sources were not readily available, and episodes associated with one person could easily be confused with those that happened to another. This was particularly the case with Charlemagnes successors.

Charlemagnes great empire started to crumble soon after his death in AD 814. His only surviving son, Louis the Pious (also known as Louis the Feeble), was deposed and restored several times by his own sons. The empire was split into three under Louiss sons and had disintegrated into many kingdoms by the next generation. The lands Charlemagne had once ruled were riven by civil war and invasions by Vikings from the north and west and Magyars from the east. Both groups of invaders reached Paris in the course of the 9th century. Charlemagnes successors included another Louis, Louis the German, and two more named Charles Charles the Bald, a grandson of the great Charles (the meaning of the name Charlemagne), and Charles the Fat, who was a great-grandson, but only a few years younger than Charles the Bald. Their nicknames give a pretty good impression of how they were regarded as rulers.

Events that happened under these successor rulers got muddled up in popular imagination with those of Charlemagnes and of his predecessors reigns. During this time of chaos, which lasted for some 200 years, people looked back on Charlemagnes time as a golden age of peace and prosperity, adding yet another element to the tendency to turn fact into fiction.

There is some evidence that full-length narratives about Charlemagne and his paladins were circulating in the 9th century, and they were certainly being told in the 10th century. It is these stories that make up a large proportion of the medieval writings known as the Matter of France, and which are the focus of this book.

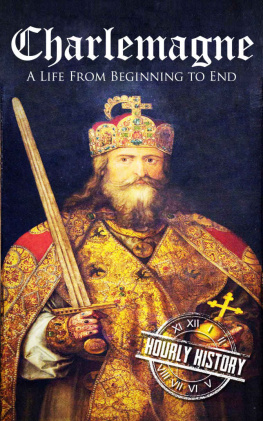

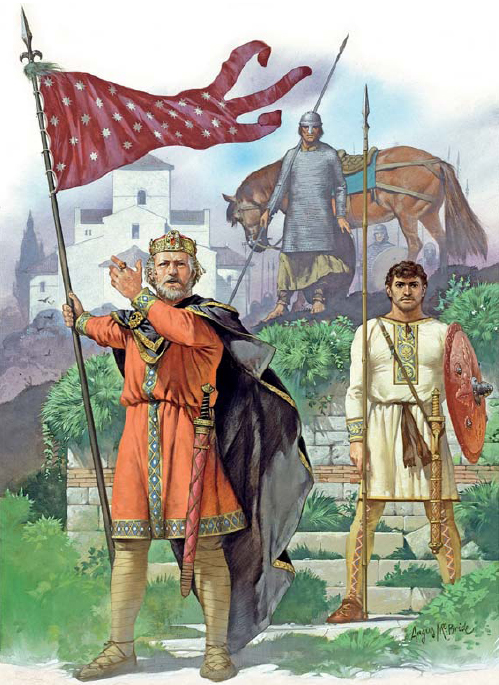

A reconstruction of the historical Charlemagne by Angus McBride. (Osprey Publishing)

C HARLEMAGNE IN H ISTORY AND L EGEND

Charlemagne so dominated his age, and his real life contained so many episodes that could come from the imagination of a storyteller, that historians still have a hard job separating fact from fiction. Fictional stories about him were circulating while those who had known him were still alive and had probably appeared before his death, in his early seventies, in January 814.

We do not know exactly when Charlemagne was born, although it must have been around 742, nor where, although in the past much energy was expended by nationalistic writers in France and Germany trying to prove that it was in their country a singularly futile exercise, as there is no evidence one way or the other. Charlemagne was born into a family of distinguished warriors. His grandfather was Charles Martel, the nickname Martel referring both to his resemblance to the Roman god of war Mars and the Old French word for the hammer. He had indeed hammered the raiding Muslims at the battle of Poitiers in 732 after they invaded from their newly acquired base in Spain. Charles Martel was not king of the Franks, but had the title Mayor of the Palace, which meant that he was effectively ruler on behalf of the last Merovingian kings, whose role was now merely symbolic. Charles two sons, Pepin the Short and Carloman, inherited power from their father, and after Carloman retired into a monastery Pepin was left in sole power. In 751 Pepin had himself declared king and made his son Charles, later known as Charlemagne, his heir.

Bertha Bigfoot

Charlemagnes mother was Bertrada (whose name also appears as Bertrade, Bertha and Bert(h)e). As the daughter of Count Charibert of Laon, she came from a very influential family. At this time, marriage was regarded as a matter of private contract and not a church matter. Charlemagne himself was to make and break a number of marriages and had a number of concubines.

At the time of Charlemagnes birth, Bertrada had a role that might be called a recognized companion although Pepin made her his official queen shortly thereafter. The real Bertrada lived a long life, dying in 782, and had an influential role in Charlemagnes early years as a ruler. In legend, however, she was to live even longer and lead an even more exciting life. There she is known as Bertha Bigfoot, the daughter of Floris and Blanchefleur, a couple who have their own long romance in medieval stories. Over 20 versions of Berthas story survive from the Middle Ages alone, so there are many variations, but the oldest versions say that Bertha was so famous for her beauty that Pepin, king of France, asked to marry her, and her parents agreed to send her to him from Hungary, where they were king and queen. She travelled with her old nurse Margiste and her daughter Alise, who looked remarkably like Bertha. On the wedding night, Margiste had Bertha abducted by assassins, and Alise took Berthas place in the wedding bed. The assassins, however, could not bring themselves to kill Bertha, so they left her to wander in a forest, where she would have died from hunger and exposure if she had not been rescued by Pepins cowherd Symon and his wife Constance.