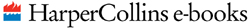

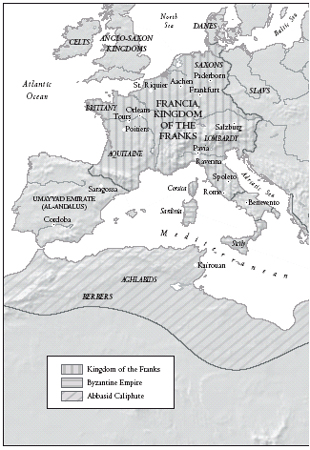

Europe, Baghdad, and the Empires of A.D. 800

Introduction

KAROLUS MAGNUS

A foreigner had come to their city, so the Romans were curious. He wasnt one of the usual befuddled pilgrims, so easily parted from their money, who fell to their knees before the altars of Romes innumerable churches. He was a king, and he was here on business.

On Christmas morning in the year 800, as the clergy chanted the praises of saints and kings, the pious rabble gathered beneath the rafters of Saint Peters basilica, along with nobles from throughout Christendom, envoys from Jerusalem, countless bishops and monks, and thousands of merchants and landlords and peasants, all straining to catch a glimpse of him. Before them all, reluctantly draped in Roman garb, stood Karl.

A ferocious blur across the medieval map: that was Karl, moving over the face of Europe like a storm and wresting new corners of his empire from the hands of his enemies while still finding time to scold his sinful monks, contribute to theological debates, and slog through muddy trenches to bark orders at canal diggers and church builders. History remembers him not merely as Karl but as Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus: Charlemagne. But on that day, he was still just Karl, king of the Franks, and this Christmas mass with Pope Leo III is one of the rare occasions when history finds him standing still.

Pope Leo was lucky to be alive. The previous year, his enemies had ambushed him in the streets, attempting to gouge out his eyes and cut out his tongue and leaving him in a bloody, naked heap. But now here he stood, able to see, able to speaka miracle, some said, unmistakable proof that Saint Peter had come to his aid.

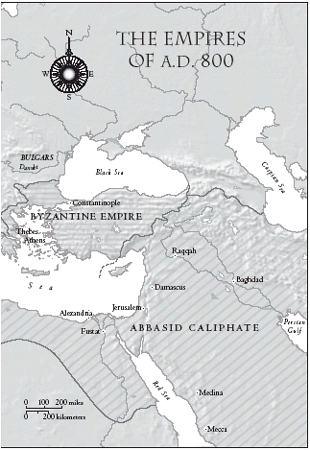

Few in the church that day could see what happened next, but the act was both instant and decisive: the pope placed the imperial crown on Karls head, fulfilling years of planning in a single swift gesture. With one voice, the entire congregation acclaimed three times: To Karl, pious Augustus crowned by God, great and peaceful emperor, life and victory! And then, in an act of ceremonial self-abasement that would long haunt the pope, Leo knelt before Karlthe first emperor in Rome in nearly 400 years.

Meanwhile, across Europe and throughout the world were the various people who had made the coronation possible: a Saxon abbot, a Greek empress, an Islamic caliph, and a Jew named Isaac, who was slowly making his way home to western Europe from Baghdad, accompanied by an elephant named Abul Abaz.

F ame came quickly for the Frankish king. Following Karls death in 814, the singers of tales memorialized him in legend and romance, while poets counted him one of the nine worthies among such rulers as David, Julius Caesar, and King Arthur. By 1100, the anonymous epic The Song of Roland had turned Karl into a bearded sage fighting alongside angels, a natural-born warrior of God; and by 1165 his church had made him a saint. In the Balkans, kral, a variant of his name, came to mean king. Medieval Icelanders crafted a saga about the mighty Karlamagns, and romances about Karls knights charmed the English well into the 1500s. The long-dead king was becoming Charlemagne, a superhuman emperor whose reputation for chivalry, piety, and power resounded to the ends of the earth. The real Karl vanished; only myth remained.

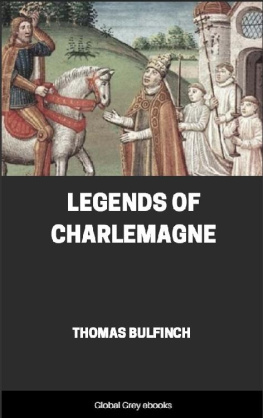

Thumb through the 1864 edition of Thomas Bulfinchs Legends of Charlemagne, with its frontispiece engraving of knights attending to a gryphon, and the esteemed emperor is there, more than 1,000 years after his death, still embodying an age when every moment promised fresh adventure:

High sat Charlemagne at the head of his vassals and his paladins, rejoicing in the thought of their number and their might, while all were sitting and hearing music, and feasting, when suddenly there came into the hall four enormous giants, having between them a lady of incomparable beauty, attended by a single knight. There were many ladies present who had seemed beautiful till she made her appearance, but after that they all seemed nothing. Every Christian knight turned his eyes to her, and every Pagan crowded round her.

The world of this Charlemagne is flooded with chivalry and perpetual miracles. It is also sheer fantasy, a romanticized medieval kingdom with the sharp edges filed down and painted with dainty fleurs-de-lys.

In reality, eighth-century Europe was a vast and shadowy forest. The stone-and-timber fortresses that supported civilization had not yet given way to storybook castles, and the trappings of chivalry were still centuries away. Karl was only beginning to build the places where his descendants would pass their winters, reimagine Europe, and tell themselves preposterous tales about their own past.

Karl started with a small Germanic kingdom, but he expanded it in the name of Christ; doing so was a right granted by God and endorsed by royal poets. With few exceptions, he dominated the battlefields of Europe as decisively as he ruled the negotiating table, and as neighboring kingdoms fell before him he gathered each of them under his banner: Aquitaine in southern France; Lombardy in northern Italy; Bavaria; Brittany; Saxony. Popes counted on him for protection, distant warlords begged for his assistance, and far-flung pagans surrendered to his authority and paid him tribute. Feared and respected, he was a good king.

To history, Karls high point was his coronation as emperor, when he unknowingly set Europe on a bold new path. Artists envisioned it, Napoleon admired it, and Adolf Hitler sought to emulate it, as did the architects of the European Union. In the meantime, the real Karl the Great was buried beneath his own reputation, remembered in legend, forgotten in fact.

After Karls death, Fortunes wheel spun, and the churches and towns of eighth-century Europe passed away, sometimes wasted by war, at other times expanded, rebuilt, or re-adorned depending on the whims of each new age. The relics of Karls era are sadly sparse: a few buildings; some coins, cups, and artwork; and a fair number of archaeological sitesbut also, most usefully, a library of several thousand books. Most of those volumes are copies of older works, cultural treasures that would have been lost if not for the diligence of Karls monks. These manuscripts preserve the memories of those who made them in the poems, chronicles, and letters that help to tell Karls story.

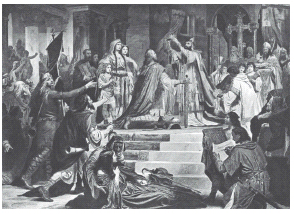

This nineteenth-century photogravure depicts the imperial coronation of Charlemagne amid swooning and suspicious glancesand a scribe who diligently writes the first draft of medieval history.

Today, the people of Karls era are remote and ghostly figures. To discover their world in letters and lyrics is to glimpse a vast universe through a half-open door; the view is frustrating and incomplete. Karl and his contemporaries left few truly personal writings, the places they knew are gone, and accurate portraits of them are virtually non ex is tent. Time swept away most traces of their lives.

But across a gulf of 1,200 years, they clamor to be heard. In history as in life, Karl emerges first: a restless, energetic warrior; protective of the papacy; overprotective of his daughters; surrounded always by brilliant men. His advisers appear next: bowing poets who flatter their king, priests and monks who offer blunt advice, hardy nobles who wage forgotten wars. Though blurry, a picture of Karls kingdom gradually comes into view, and with patience we can see them: giggling princesses, borderland heretics, exhausted peasants, all of them praying in sunlit chapels or driving carts through market squares. In the background, perhaps surprisingly, are Jews. They immerse themselves in the labors of Karls kingdom, enjoying the autumn of a fleeting golden age.