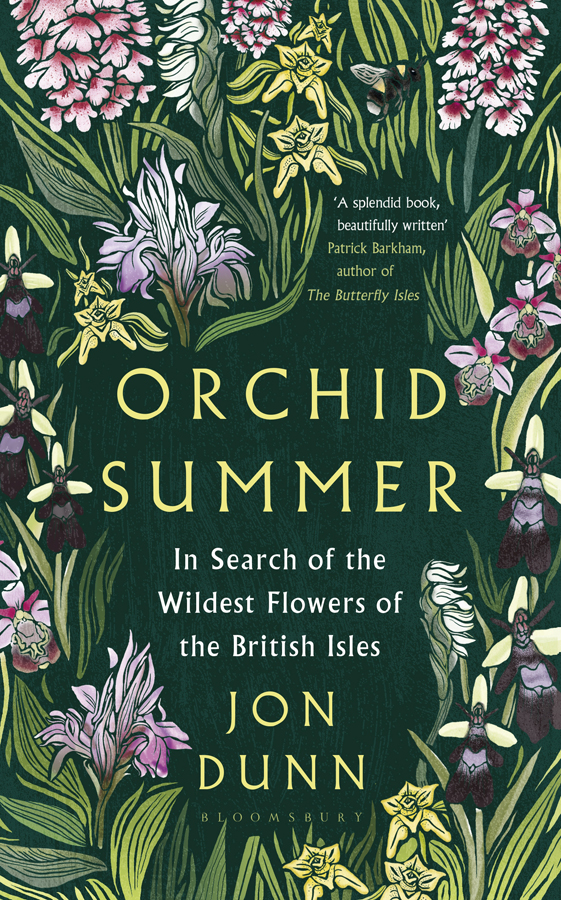

ORCHID SUMMER

For Roberta and Ethan, with love

Contents

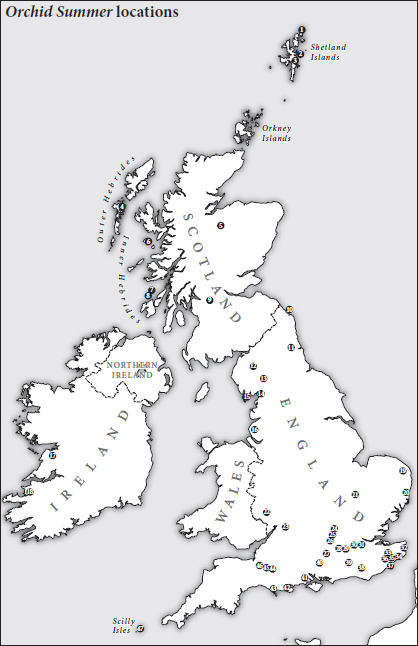

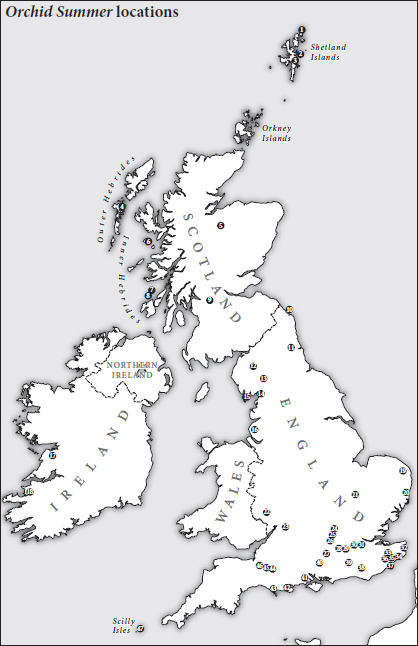

Unst, Shetland

Whalsay, Shetland

Catfirth, Shetland

North Uist, Outer Hebrides

Cairngorms, Scottish Highlands

Rum, Inner Hebrides

Colonsay, Inner Hebrides

Oronsay, Inner Hebrides

North Kelvin Meadow, Glasgow

Lindisfarne

Wylam, Northumberland

Hutton Roof, Cumbria

Little Asby Outrakes, Cumbria

Gait Barrows NNR, Lancashire

Sandscale Haws, Cumbria

Ainsdale-on-Sea, Merseyside

The Burren, County Clare

Ballyheigue, County Kerry

Sutton Fen, Norfolk

Sizewell, Suffolk

Cambridge

Haugh Wood, Herefordshire

Stroud, Glos

Princes Risborough, Bucks

Homefield Wood, Bucks

Hartslock, Oxon

Noar Hill, Hants

Sheepleas Nature Reserve, Surrey

Ranmore, Surrey

Downe Bank, Kent

Eynsford, Kent

Sandwich Bay, Kent

Bonsai Bank, Kent

Samphire Hoe, Kent

Park Gate Down/The Hector Wilks Reserve, Kent

Wye Downs, Kent

Dungeness, Kent

Mount Caburn NNR, East Sussex

Wakehurst Place, West Sussex

Chappetts Copse, nr Selborne, Hants

New Forest, Hants

Dancing Ledge, Dorset

Radipole Lake, Dorset

Sparkford, Somerset

Great Breach Woods/Babcary Meadows

Curry Rivel, Somerset

St Marys, Scilly

The hill in question was steep, and came at the end of our family walk out of Curry Rivel, across the sheep-pared field that surrounded the Monument, along the damp flank of the saturated Levels and thence back up to the village. It was early April, at the back of a wet and interminable winter, and the walk had been muddy. My dad was in a hurry to get back to the fireside, and my mum to our allotment, where there was digging and work to do. Red Hill was all that stood between us and an afternoon of predictable family life. I was lagging behind my parents as we tackled the incline, scraping thick wedges of Somerset mud onto the tarmac from the soles of my boots. I longed to stay down on the Levels, to see what wildlife I could find. The bubbling calls of curlews were receding as I headed reluctantly homewards.

It was at that moment when everything changed for ever. My mum was calling me from somewhere out of sight, and my head must have lifted in response to her impatient summons. There, high on the grassy bank that rose steeply above the lane, was a lone purple flower. Heedless of the brambles that laced the grass, I scrambled up to it I knew what I thought it was or, rather, what I dearly wanted it to be. This, surely, was my first orchid.

Nobody shared my love of the natural world certainly none of my peers, and definitely neither of my parents. I think they were always slightly bemused that it was all I cared about. I found people baffling and school relentless endless weeks of petty restrictions, rules and incomprehensible lessons. Whatever I could discover in the countryside around our small house, I wanted to identify, to learn everything there was to know about it and, occasionally, to take home with me to marvel at some more. This was tolerated in some instances half a blackbird eggshell on my bedroom windowsill was fine and less so on other occasions: for example, my plans to keep slow-worms in my bedroom foundered in their infancy.

My reference materials in those early days were meagre three volumes of the Observers series, covering butterflies, birds and wildflowers. I devoured their pages, eager to see every species they contained. During our first summer in Curry Rivel, it was the butterflies first and foremost that caught my eye. I suddenly found butterflies wherever I looked. Our garden, so sterile and tame, at least had flaming small tortoiseshells and velvety peacocks on the buddleias, but once I started to explore beyond the village limits, I found countless treasures. I wandered hills shimmering with common blues like fragments of sky at my feet, sought chocolate-brown and burnt-orange gatekeepers defending stretches of hedgerows frosted with pink and white dog roses, and chased the fleet, saffron clouded yellows that eluded my every attempt to catch them racing through fields of red and white clover. In autumn, while I stole apples, pears and plums in abandoned orchards behind wooden gates lost in a choke of blackthorn and brambles, drunken red admirals feasted at my feet on fermenting windfalls carved hollow by drowsy wasps.

As autumn washed into winter, the water in the rhynes that bound the Levels rose inexorably. Soon vast silver sheets covered the fields below the village as far as the eye could see. I became more aware of birds the Levels pulsed with wildfowl, while snipe exploded in front of my feet as I picked my way through sodden meadows. My usual routes through the fields were often rendered impassable by water, and more than once I relied on the kindness of farmers to lift me over swollen rhynes in the bucket of their diggers. Our garden, meanwhile, briefly hosted redwings, impossibly exotic thrushes for one who had only noticed blackbirds and song thrushes hitherto. School and the short winter daylight meant my wanderings were severely curtailed, and I returned to the Observers Book of Wildflowers for inspiration on the dark evenings while my parents watched the news and I lay on the rug in front of our wood fire.

I yearned for summer and the return of the butterflies. Before they could come, there would be flowers as the world sparked into life once more. I had no idea how scant the coverage of Britains wildflowers was in the poor little Observers guide. These modest books were my bibles, and I took communion from their pages. My fervour was reserved for one family alone that winter I read the descriptions of the orchids over and over again, and tried to find out more about them at our local library. I took what little I could glean home with me, like a special pebble brought back from the beach and set on a shelf to be admired daily. Now I knew what our orchids were: part of a vast plant family that ran into thousands of species, they had simple leaves but marvellously complex flowers comprised of three sepals and three petals, with one of those petals usually radically different from its fellows. Looking at illustrations in books, I found them utterly glamorous, so improbable and unlikely to be found in the waterlogged countryside around our little house. I longed to see one nothing else would do.

When the moment came, on the sides of Red Hill, it had an intensity that I remember vividly to this day. Indeed, even now when I see a new species of orchid, I get a sense of the hypersaturated perception of reality that gripped me that afternoon when I knelt beside this keenly anticipated plant. The leaves were dark, glossy green, and heavily blotched with deep, bruised markings, like leopard spots that had run in the wash. But it was the flower that captured me held proudly above the leaves by a thick, fleshy stem, the individual blooms were delicate, curving sculptures of a rich, royal purple with a clarity and intensity of colour quite unlike any flower Id ever seen before. I felt breathless.