About the Book

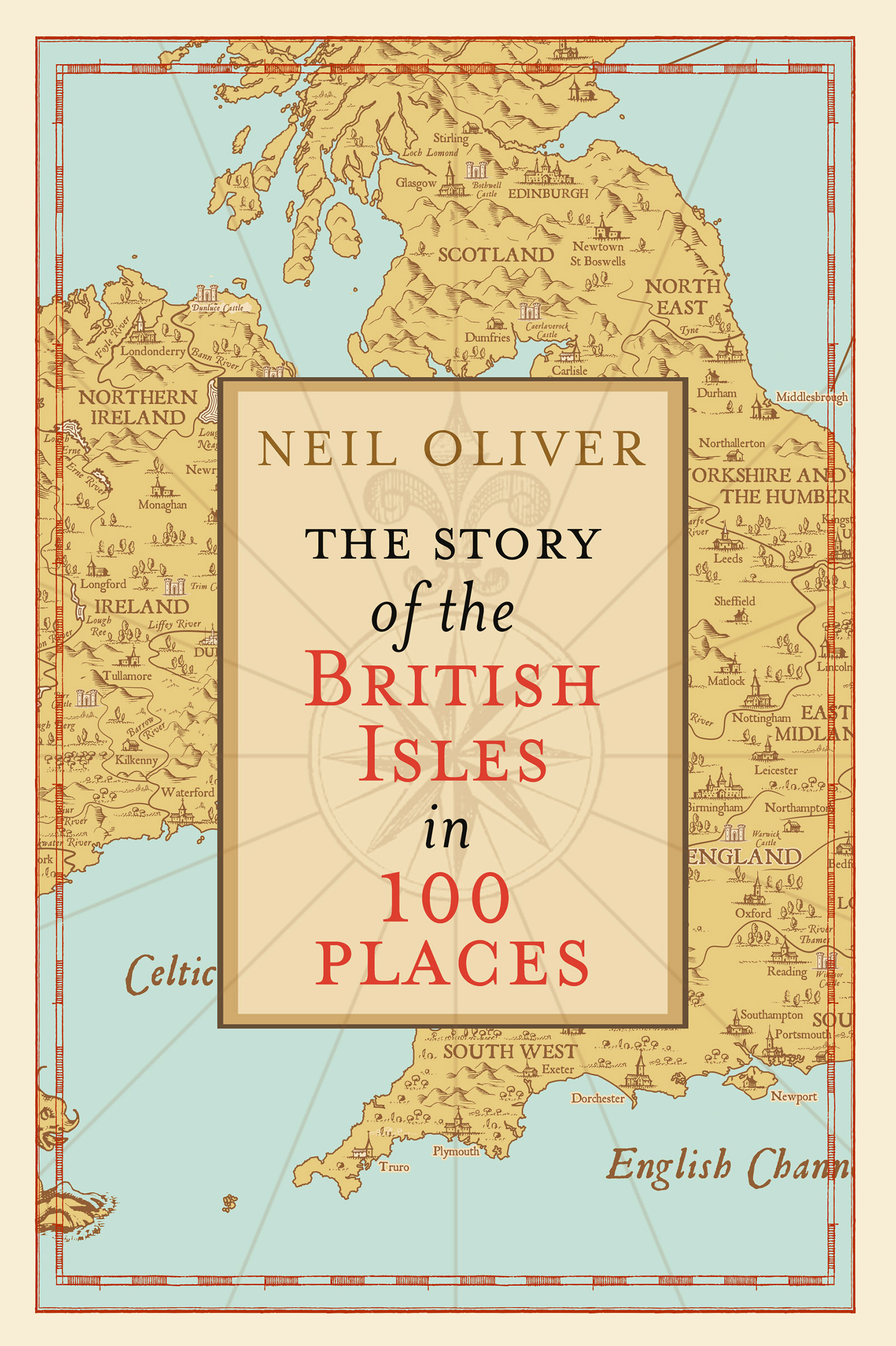

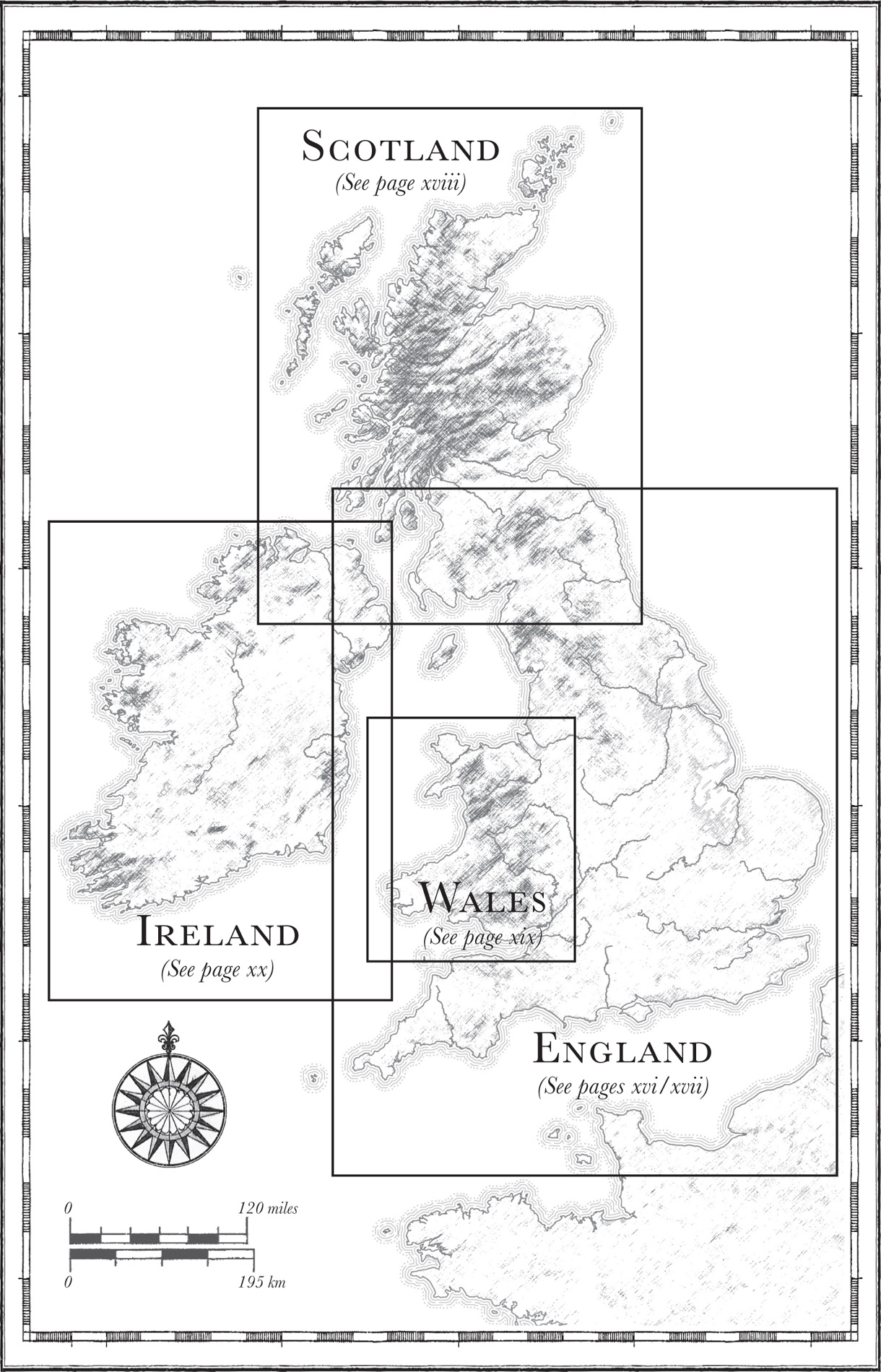

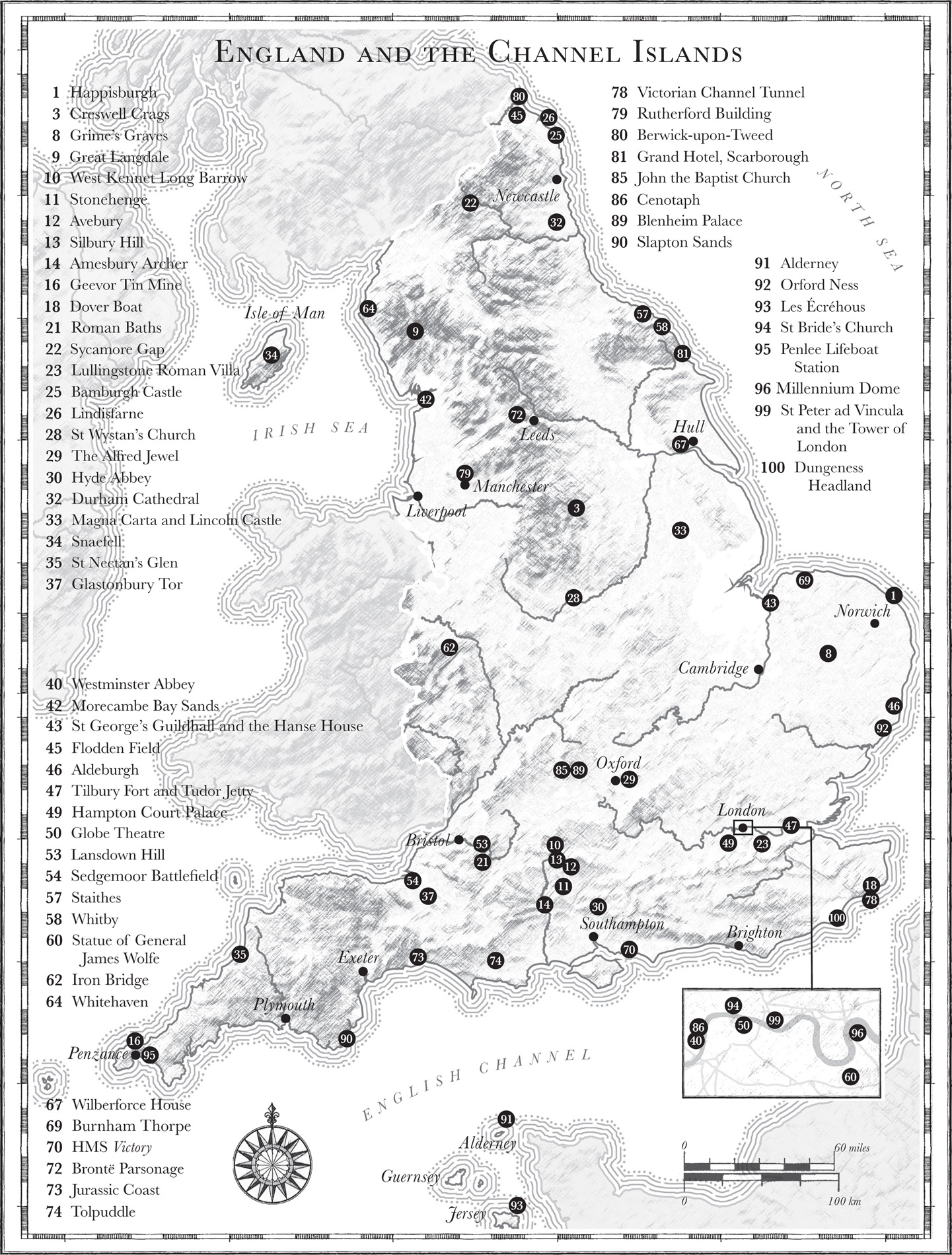

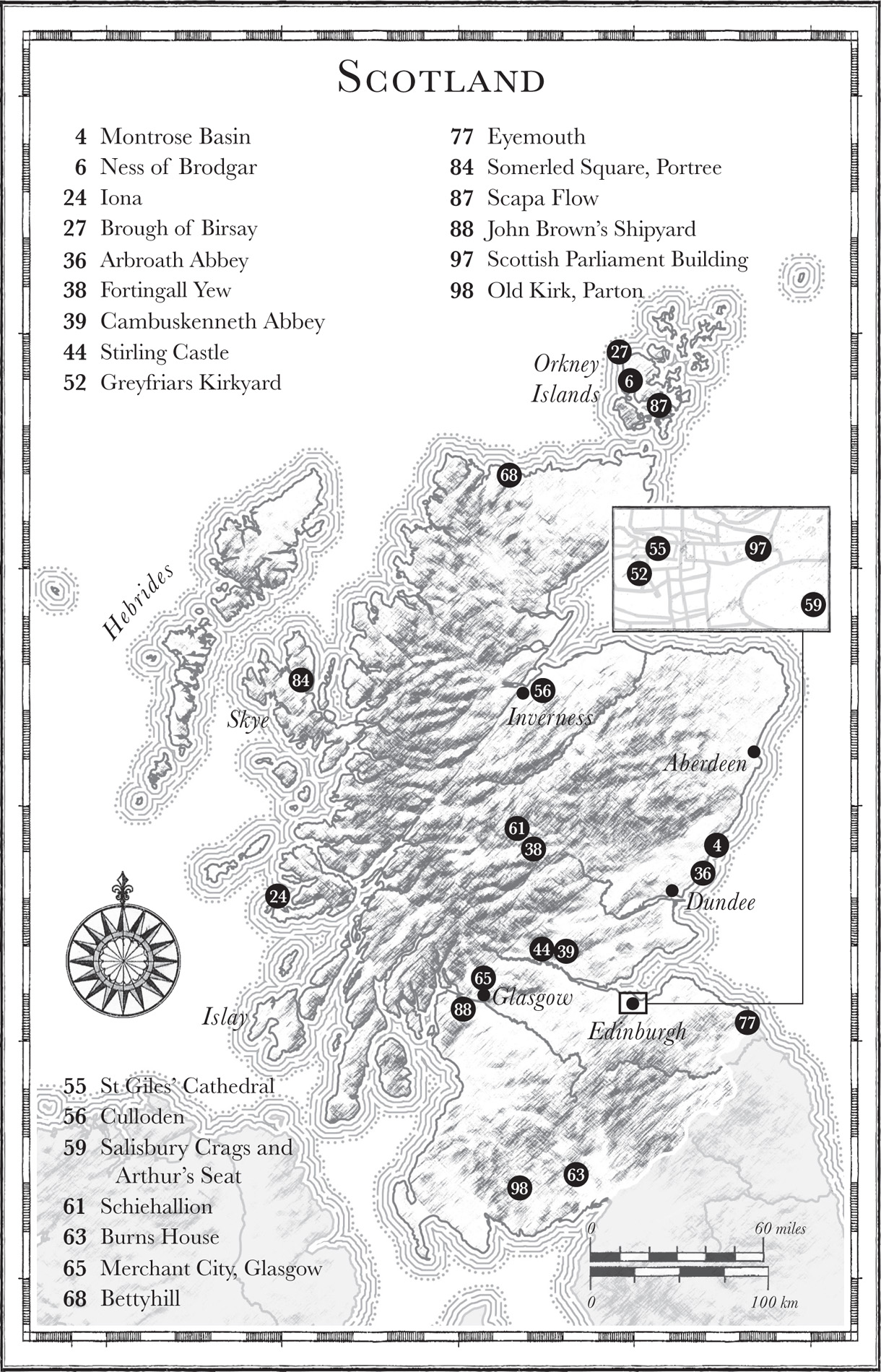

The British Isles, this archipelago of islands, is to Neil Oliver the best place in the world. From north to south, east to west, it cradles astonishing beauty. The human story here is a million years old, and counting. But the tolerant, easygoing peace we enjoy has been hard won. We have made and known the best and worst of times. We have been hero and villain and all else in between, and we have learned some lessons.

The Story of the British Isles in 100 Places is Neils very personal account of what makes these islands so special, told through the places that have witnessed the unfolding of our history. Beginning with footprints made in the mud by humankinds earliest ancestors, he takes us via Romans and Vikings, through the flowering of Christianity, to civil war, industrial revolution and two world wars. From windswept headlands to battlefields, ancient trees to magnificent cathedrals, each of his destinations is a place where, somehow, the spirit of the past seems to linger. Beautifully written, his book is majestic, awe-inspiring, a kaleidoscopic history of a place with a story like no other.

Contents

For more information on Neil Oliver and his books,

see his website at www.neiloliver.com

To my mum and dad,

Norma and Pat

List of Illustrations

. The Ness of Brodgar, Orkney

. Mace head, Newgrange and Knowth, County Meath

. Cantrer Gwaelod, Borth, Ceredigion

. Lyn Fawr, Cynon Valley, Mid-Glamorgan

. Dn Aengus and Dn Dchathair Forts, Inishmore

. Head of Sulis Minerva, Roman Baths, Bath, Somerset

. Mosaic floor, Lullingstone Roman Villa, Kent

. Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland

. The crypt, St Wystans Church, Repton, Derbyshire

. The Alfred Jewel, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

. Durham Cathedral

. St Nectans Glen, Trethevy, Cornwall

. The Fortingall Yew, Perthshire

. Harlech Castle, Gwynedd

. Stirling Castle

. Map of Aldeburgh (1588), Suffolk

. Lacada Point, Antrim Coast

. The Globe Theatre, Bankside, London

. St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh

. Schiehallion, Perthshire

. The Iron Bridge, Coalbrookdale, Shropshire

. Auction of Slaves sales bill (Wilberforce House, Kingston upon Hull)

. HMS Victory, Portsmouth Historic Dockyard

. The Bront Parsonage, Haworth, West Yorkshire

. The Cobb, Lyme Regis, Dorset

. Fastnet Rock, off County Cork

. The Grand Hotel, Scarborough

. Somerled Square, Portree, Isle of Skye

. John Browns Shipyard, Clydebank, West Dunbartonshire

. The Odeon, Alderney, Channel Islands

. Les crhous, by Jersey, Channel Islands

. Glen Lyon, Perth and Kinross

Introduction

PEOPLE STOP ME in the street and say, Youve been everywhere which are the places I should visit?

I usually stall for time, saying theres so much, so many places that I hardly know where to start. This is true. When the question comes out of a clear blue sky, its like being asked to name my favourite book: for a few moments I cant think of any books at all, far less any contenders for the number-one spot.

But after careful consideration of that places question, this book is the answer I have to give.

The stories and places relevant to telling the story of these British Isles are like stars in the night sky, too numerous to count. At first sight their volume is overwhelming. But if you have someone to point out the patterns the constellations, planets and galaxies then the mass of it begins to make sense.

I have seen a great deal of the British Isles. I have circumnavigated the archipelago several times. The coast is like the hem of a garment fixing the whole against unravelling but I have explored the interior as well. I have viewed these islands on foot, from microlights, helicopters, stunt planes, vintage aircraft, trains and automobiles, and from every kind of seagoing craft a person might imagine, from kayaks to warships. I have looked out from the summits of lofty peaks, the tops of lighthouses, through castle battlements, from church roofs and city tower blocks. I have even been under the sea in scuba gear and on board a nuclear submarine. Now and again I have considered the possibility that I have seen more of these islands, in a shorter time, than anyone else.

Why do we remember the places we remember? The particular places in the landscape that we commit to collective memory that we write about and photograph and thereby make monuments of are a skeletons bones poking through skin. We, the people, are the flesh thin, fragile and soon to decay. The skeleton lasts longer, perhaps for ever. We are continually drawn, in wonder, fascination, fear, sadness, joy, to where the white of bone has been revealed by great and terrible moments. The attention paid to certain places and times and, where appropriate, to unforgettable human characters who helped make those places and events significant is part of how we seek to remember who we think we are as a people and as a nation.

After all my travelling around the islands, some sites and stories have stayed with me. I have also made destinations of a handful of objects artefacts, even the written word since these too are worthy of a visit, time spent. The Story of the British Isles in 100 Places is a personal sketch rather than a full-blown painting. I have chosen what I consider to be the most characteristic features of the face I have grown to know and love. What they have to say seems to me fundamental to an understanding of the long, slow shaping of the British Isles we live in today. In this present climate of public fear, disagreement and uncertainty about the future, I think it is timely to look again at the past, the story of this place from its earliest times.

How did all this happen? Why did a tiny group of islands off the coast of north-west Europe come to exert such influence over a whole planet? During the past fifteen years I have seen enough of the wider world to realize that the answer lies in the nature of the place. It is a place, a landscape, built of the fragments of ancient continents Gondwana, Pangea

Some of the rock here is not much younger than Planet Earth itself. The gneiss of Lewis and parts of Scotlands north-west are perhaps three and a half billion years old. Here and there upon rocks elsewhere in the isles are the footprints of dinosaurs that walked across those land rafts long ago, leaving their marks in silts and sands that were themselves transformed into rock by pressure and heat and time. The ragged slivers that finally came together as an archipelago, hundreds of millions of years ago, have the worlds back-story ribboned through them like brightly coloured writing through a stick of Blackpool rock.