T H E

V I K I N G S

A H I S T O R Y

N E I L O L I V E R

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To Mindy Alexa-Rose Hutton and Sonny John Wallace at the start of the journey

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

SECTION ONE

SECTION TWO

SECTION THREE

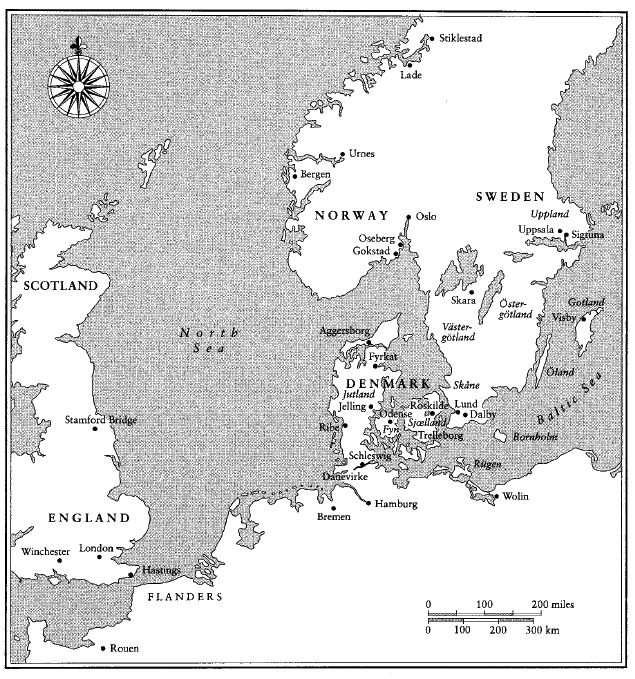

Viking Scandinavia

INTRODUCTION

Some years ago I spent a day on the island of Canna, off the west coast of Scotland, in search of sea eagles. Once widespread throughout the British Isles, they were killed off by livestock farmers who saw them as no more than vermin, a threat to their flocks. The north and west of Scotland became their only redoubt, but the last of the native birds was gone poisoned, trapped or shot before the outbreak of the First World War.

In 1975 the Nature Conservancy Council embarked upon a reintroduction project. During the following 10 years 82 eaglets were raised in captivity on the Inner Hebridean island of Rum, and gradually released into the wild. Since the British population had been completely exterminated, the project had depended upon sea eagles sourced elsewhere. In fact, the birds that have gradually repopulated the north and west of Scotland came from Norway.

Although the reintroduction has been a success it still takes some effort and not a little luck to catch a glimpse of the birds themselves. I had been on the lookout all day and, while I had spotted a nesting site, it was abandoned. It seemed that was as close as I would get, until all at once a great black shape appeared in the sky, backlit by the setting sun. Unless and until you have the privilege of seeing a white-tailed sea eagle in the flesh, or rather feather, it is hard to do justice to the experience. The adult birds are three-and-a-half feet long from hooked yellow beak to stubby tail and have wingspans well in excess of eight feet. In flight they have the shape and bulk of flying barn doors. Imperious in the extreme, the shadow drifted past with scarcely a beat of those wings. Trapped by the surly bonds of Earth, I was beneath his contempt and he paid me no heed. As he sailed by, king of the sky, I felt the hairs rise on the back of my neck. He was out of reach not just because he soared so high, but also because he was wild. Grounded below, I was a domesticated creature, cosseted and docile.

In the intervening years I quite forgot about my sea eagle, but he came to mind once more as I began to contemplate this project about Vikings. How appropriate it seemed that we had turned to Norway in hopes of reclaiming, restoring some part of our former wildness. A thousand and more years ago, it was another group of strangers from Norway who arrived to show what might be done by travellers who recognised no limits, no borders. The Vikings, too, had descended out of the blue, eagles of the north, and their presence changed us for ever.

So when I started writing this book, I had a grand plan. What had always been apparent to me about those ancient Scandinavian interlopers was the sheer force of their personality. No matter how hard I had striven for objectivity and a clinical, scientific approach to the age that bears their name, I never quite escaped the simple power, the thrill of the word Viking. I hear it and all at once my imagination conjures up dragon-headed long ships, brightly painted round shields and bloodied battleaxes, long-haired and bearded wild men bent on rape and pillage, monasteries engulfed in flames. Then there are the names of the men themselves (and they are always men): Eirik the Red, Leif Eriksson, Harald Hardrada, Eirik Bloodaxe its all there, fully formed, like a scene in a pop-up book for children. I cannot think of another people from history Goths, Huns, Moors, Mongols, Normans, Tartars, Vandals whose name alone evokes such a complete picture.

It seemed obvious that what was needed was a biography of the Vikings. Since the image is so potent and so clear, surely it would help to think about them not as a people, but as a person. In the manner of a biographer, I would start with the world from which they emerged, the events that shaped the society that, in turn, shaped them. As I said, it seemed a grand plan.

On the face of it there appears to be enough information available to allow for the composition of a lifelike portrait of the Vikings. There are three main sources: written records, plentiful coinage and archaeology. Most captivating to begin with are the words of the sagas, the chronicles and annals, the poetry and the rune stones. There is certainly plenty of material to be going on with; but the problems for the scholar range from the completeness or otherwise of the manuscripts themselves, to the objectivity and accuracy of the account contained within. Common to all is the inescapable fact that with the exception of the rune stones which, anyway, provide little more than names and boasts not a word of it was written by the Vikings themselves. The sagas and poetry were at least composed either by Scandinavians or people of Scandinavian descent, but centuries after the events recounted. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the church annals, the accounts of Arabic travellers and all the rest came from people to whom the Vikings were incomprehensible strangers at best and Godless, pitiless murderers and destroyers at worst. All of it makes for reading that is stirring, unforgettable, beautiful, harrowing and horrifying by turns but all of it is the work of authors with their own axes to grind.

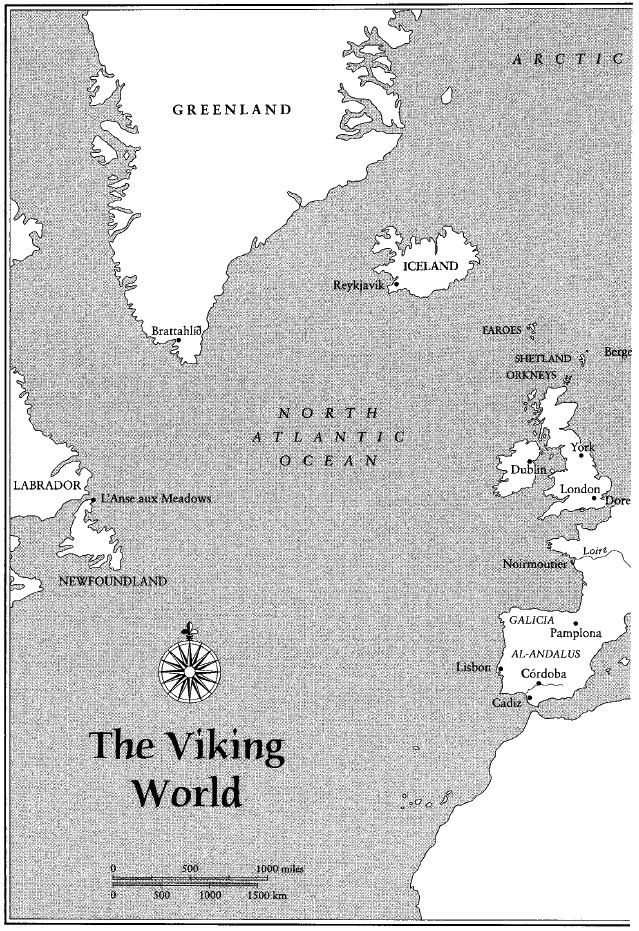

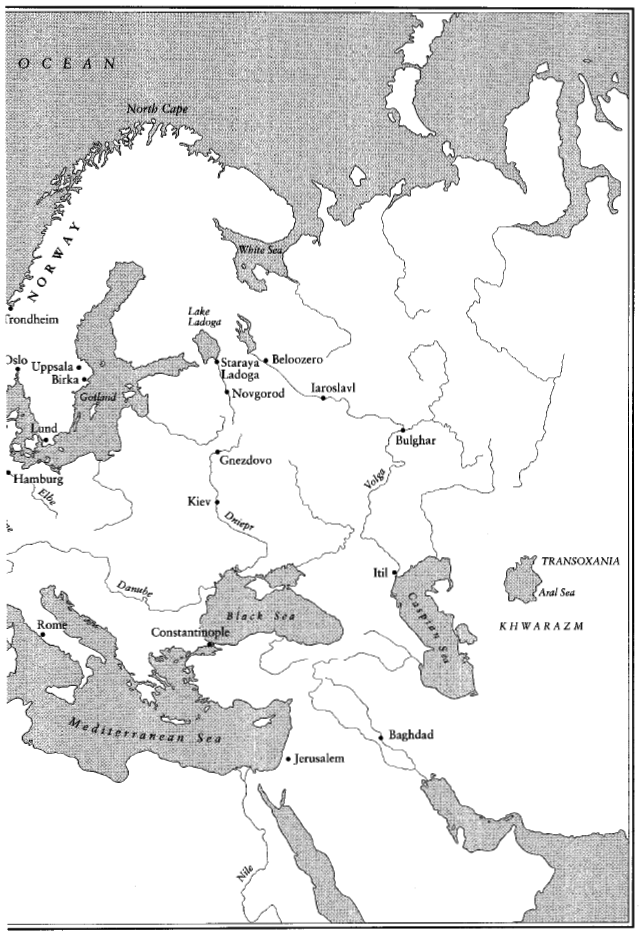

The men and women we call Vikings came not from one country but from three, namely Denmark, Norway and Sweden. To add to the confusion, they emerged into the wider world at a time before those countries had labels. Part of all that resulted, from the so-called Viking Age, was the very creation of those states or at least the laying down of their foundation stones. Perhaps it might even be best to set aside the word Viking in favour of Northman, from Nordmenn or Nordmanni, the names preferred by many of those that encountered the travellers and adventurers who descended from the top of the world as the eighth century gave way to the ninth.

Having considered the written sources and learnt to be wary of them a would-be student of the Vikings might turn hopefully to the evidence of the coins. There are plenty of them as well indeed tens of thousands scattered across Europe from east to west and north to south. Many of them are the coins of peoples the Vikings encountered, and the results either of honest trade or plain robbery. Plentiful, too, are those they made and stamped themselves. Such finds might seem to offer a sense of order, some fixed points within the otherwise whirling maelstrom of uncertainty. They have upon them, after all, the mute faces of kings, along with both their names and the names of places where they were made. Surely their testimony must be honest, and without bias?

At first they were made to mimic the coins of other realms England, France and the lands of the Middle East but later they had their own identity. Once self-assured Viking kings emerged, they took to underlining their own power and position by making sure their likenesses were known to all. But while the coins themselves can often be accurately dated, those dates provide little in the way of certainty about the contexts in which they are found. Put simply, a coin only gives a date