This book is for the dedicated souls who give their time and often show great courage and personal sacrifice in protecting wildlife. You know who you are, and I salute you.

The opinions and feelings expressed in this book are my own. This is a description of a quest for knowledge and understanding, and I wont claim that all of the answers are right. Nature does not give up her secrets easily. It has been necessary in one or two instances to change the names of people and places.

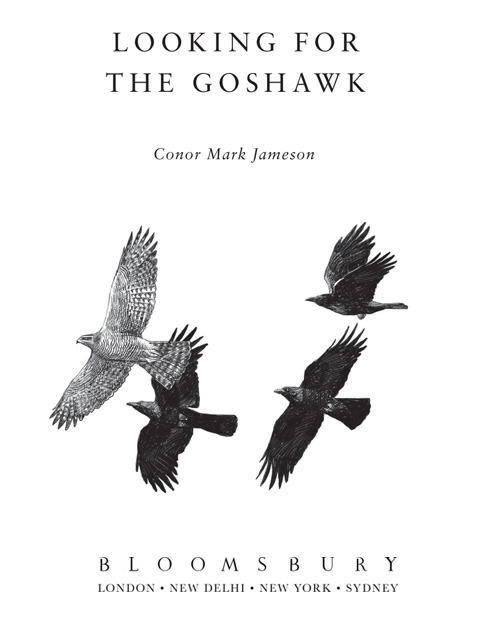

Copyright 2013 text by Conor Mark Jameson

Copyright 2013 inside illustrations by Toni Llobet

Copyright 2013 cover artwork by Darren Woodhead

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2013 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

The right of Conor Mark Jameson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978-1-4081-8702-9

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

Contents

***

***

To write something which was of enduring beauty, this was the ambition of every writer the artist yearned to discover permanence, some life of happy permanence which he by fixing could create to the satisfaction of after-people who also looked Wheelwrights, smiths, farmers, carpenters, and mothers of large families knew this.

T. H. White

The Goshawk

Part 2, Wednesday

1937

Goshawk. Dave utters the word, the name, quietly. Partly to me, I sense, and partly to himself. He doesnt have to speak loudly, here. The forest is quiet. Cathedral quiet. Beyond its roof the silence but not the peace is disturbed only by the sporadic inhalations of breeze into forest canopy, a hundred feet or more above us. The tinkle of a burn or stream deadened, softened by mossy banks and soggy fallen branches, adds further mood music, easy to miss unless you stay still, as we are doing now. And listen. I think subconsciously we are listening for the Goshawk. A faint hope. The Goshawk gives very little away. Why should it? It sees like a demi-god. And hears. It moves like an apparition, guided by a rocket. It may not even be here. Except in our heads. In our heads it is vivid.

The forest floor is open, lurid with the tones and textures of fresh moss, in clumps and swathes, rugs and stair runners on both steep and gentle slopes, enveloping and enfolding rocks and wind-snapped trunks, stumps and branches in turn. This is outdoors as room. Padded. Comfortable and comforting. Mild and wild. Semi-natural. Sauvage, in a second-hand way. I feel relaxed, at home, soothed by sylvan ambience, by the softened edges, the scent of moss, toadstools, soft earth. At the same time I am hyper-alert, sensitised. Im in a place Ive never been, with a man Ive only just met, yet the sense of belonging is assured.

The roof of the forest is propped on clear, scaly, perpendicular tree trunks. These are straight, and true, and solid as the pillars of a living temple: Norway Spruce, Japanese and continental European Larch and Sitka Spruce trees; widely spaced, long-since thinned of near neighbours to promote growth over the course of their 80 years lived so far. They have been here since planting between the wars, the first phase of the modern era moves to make Britain more self-sufficient in timber, and paper pulp, less vulnerable to the vagaries of international diplomatic relations. Farmed trees. We were putting some forests back, in most cases a new kind of forest cover. We were using trees from Scandinavia, Japan (the larch) and North America (the Sitka), in the main. Of the fast-growers these are better suited to our wetter, thinner, more acid soils. They grew quicker and straighter though much less attractively than even the native so-called Scots Pine, the tree that edged north behind the retreating ice of the last glaciation to encase large areas of the northern, less hospitable parts of our isles.

It is tempting to scorn these plantations, thinking them dark and lifeless. But in maturity, like this, thinned out and given some encouragement, these woods and forests assume a grandeur and charm of their own. They are trees, after all. They will at last begin to look and feel more settled, more at home, to recapture nutrients, build soil, sustain life. The life in and around them is starting to find its feet, although the signs of human forest industry are never far away. This is not the picture postcard romanticism of the Caledonian wood, with its heather and blaeberry under-storey, its Capercaillies where these survive and its Red Deer stags. But it is proper forest in its own way. Somewhere now worth exploring, somewhere with secrets to divulge. Artifice, perhaps, with an underlying commercial purpose, for sure, but there is beauty here too. My views on this have changed. Looking for the Goshawk has helped.

Goshawk?

Dave and I are crouched like detectives beside a scattering of feathers at the base of one of these thick, iron-solid and branchless lower trunks. The feathers are fresh, still buoyant, alive, almost, on a bulging knoll of sphagnum moss, itself feathery, but also moist, soft and spongy to the touch. A comfortable death-bed.

Daves terrier Hamish is sniffing the feathers closely. Some, from the victims tail, show traces of pink-red where the tips of the shaft have been pulled, intact, from a rump. A downier breast feather is sticking lightly to Hamishs muzzle. It shivers on his breath. He makes no attempt to remove it. Perhaps he cant feel it. He looks suitably sombre, tactful. Paying his respects. He is probably taking his cue from us. Well, David.

The larger feathers wing primaries and secondaries are mainly brown, barred fawn and off-white. The breast feathers are more numerous, spotted and striped brown on a paler background. Some move in the vaguest air current, drifting. They definitely havent been here long, maybe even minutes, if not hours.

They are hawk feathers. Sparrowhawk. Female. Adult. A large enough bird in itself. An accomplished predator, usually of birds. And here it is, itself depredated. No trace remains of its body.

When Dave said Goshawk he wasnt misinterpreting the traces of the find we are now kneeling beside. He was naming the nemesis: the bird that almost certainly killed it, plucked it here, and took its body away to consume in secret, perhaps even at a nest. We hope a nest. But this is the only sign we have found. The only hint.

We can rule out Tawny Owl? I venture, after a while, taking some photos of what at this moment feels like a crime scene, of sorts. Perhaps something will come to light later, in a moment of calm reflection on these pictures.

Next page