Copyright

Copyright 2010 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2010, is an unabridged republication of The Englishwoman in America, originally published by John Murray, London, in 1856. A new Introduction by Clarence C. Strowbridge has been specially prepared for this Dover edition.

International Standard Book Number

9780486141299

ISBN-10: 0-486-47309-0

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

47309001

www.doverpublications.com

INTRODUCTION

When Isabella Lucy Bird Bishop died in 1904, a week before her seventy-third birthday, she had been a celebrity for over twenty-five years. Her fame was due primarily to the popularity of her eight travel narratives, beginning with her book on Hawaii, first published in 1875. But over the years it had been enhanced by the hundreds of lectures she gave in England and Scotland on social, political and religious issues, as well as by the British publics increasing awareness of her numerous charitable acts on behalf of poor people at home and abroad. In 1882 she had been accorded the great honor of being the first woman Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society. Since her death, her reputation has grown so that now she is acknowledged not only as the greatest of all the Victorian lady travelers, but also as an outstanding representative of English Victorian culture. Most of her travel books are still readily available and continue to delight and inform large numbers of readers. In 1989 she turned up as a featured character in British dramatist Caryl Churchills Top Girls, a classic feminist play that is often revived. And if you Google her name today, you will discover not only several websites devoted to her life and travels but also the site of a California-based manufacturer and merchandiser of upscale travel apparel for women, named in honor of this extraordinary woman. Long live Isabella Bird!

But when the present book was first published, early in 1856, under the title The Englishwoman in America, Isabella Bird was not famous at all. It was probably because she had no name recognition (after all, she was only twenty-four) that it was published anonymously, but old-fashioned British upper-middle-class reluctance to enter the limelight may also have been a factor. It is still the least known of her books.

Isabella was born on October 15, 1831. Her father, Edward Bird, was a zealous, newly ordained Anglican minister who had returned to England in 1829 after a brief, sad career as a barrister in Calcutta. His young bride had died of cholera there not long after having given birth to their son, and the child had died three years later. After coming back to England and undergoing an intense religious experience, he studied for the ministry, and in 1830, at the age of thirty-eight, was appointed curate of the small town of Boroughbridge in Yorkshire. His religious orientation was not surprising inasmuch as several members of his family were prominent in the evangelical sect of the church. Two of his close relatives were bishops (one became archbishop) and several were missionaries in India and other far-flung parts of the British Empire. Shortly after his arrival in Boroughbridge he had married Dora Lawson, a highly educated daughter of the Reverend Marmaduke Lawson, one-time prebendary of Ripon Cathedral. Isabella was their first child.

Edwards strong religious beliefs, particularly on behalf of totally work-free Sabbaths, led to uncomfortable relations with many of his farmer parishioners and consequently to a number of somewhat awkward reassignments to towns in Berkshire (where a second daughter, Henrietta, was born in 1834) and Cheshire, then to the industrial metropolis of Birmingham and, finally, to the quiet village of Wyton in Huntingdonshire. Thus the two young girls were moved around a good bit in their formative years. They never had any formal schooling, but both thrived under the dedicated tutorship of their parents, who treated them like little adults. Recalling those days, Isabella once said, No one can teach now as my mother taught; it was all so wonderfully interesting that we sat spellbound. Because Isabellas health was always fragile, her parents and medical advisors felt it best to keep her in the fresh air as much as possible. She learned to ride horses when she was little more than four years old, and then accompanied her father on his pastoral rounds. As they rode side by side, Mr. Bird would point out natural and manmade features, such as flowers, trees, planted fields, barns, mills and dairies, and later would quiz her closely as to what she had seen. Many years afterward she was asked to what she attributed her extraordinary talent for accurate observation. To my fathers conversational questioning upon everything, she replied.

Isabellas health problems continued throughout her childhood and youth. She suffered from depression and insomnia and was often in pain. In 1850, when she was eighteen, she underwent an operation to remove a spinal tumor, which was only partially successful, so her young adulthood was punctuated by long periods in which she would have to spend entire mornings in a semi-recumbent position. Perhaps her doctor realized that many of her physical and emotional problems stemmed from an extraordinary intelligence and a strong personality at odds with a stultifying social environment; in any event, he prescribed an extended ocean voyage. In 1854 Isabellas father gave her 100 and permission to travel as long as the money lasted. She chose to travel to North America and made it last for almost six months. This book is her entertaining and historically valuable account of that first, life-changing journey.

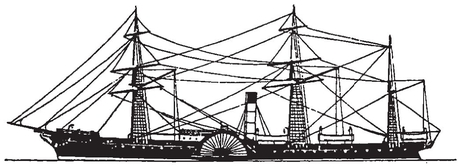

AMERICA, NIAGARA, EUROPA, CANADA

Isabella traveled to North America on the Canada and returned to England on the America. These were two of four sister ships built in 1847 and 1848 for the Cunard company, which had the contract to carry the royal mail across the North Atlantic. It had a wooden hull, one funnel and three masts, and was 251 feet long and 38 feet wide. It accommodated about 170 passengers in two classes and a crew of ninety. Powered by two one-cylinder engines, it weighed in at 1,831 gross tons; its coal bunker capacity was 450 tons, which its sixteen burners consumed at the average rate of sixty tons a day. There is a delightful diary of a familys trip from Liverpool to Boston via Halifax on this very ship in 1856 at http://personalpages.tds.net/~jonwalton/Diary.html . It describes in wonderful detail the configuration of the vessel, the living and sleeping quarters, the passengers activities, the meals served and the often turbulent conditions at sea.

In her book, Isabella is curiously vague about dates and other facts that she undoubtedly thought both personal and mundane, but that are of natural interest to the modern reader. In the first chapter she tells us only

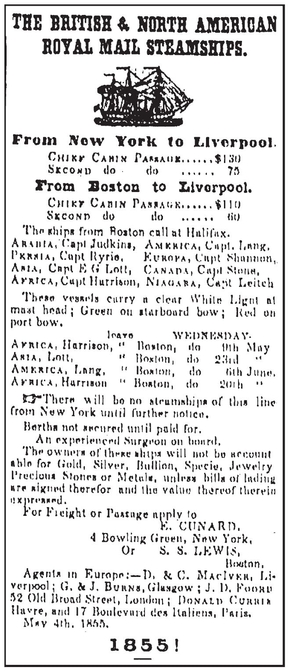

This 1855 advertisement created for the American agents of the Cunard line shows that the ships left Boston for Liverpool via Halifax every other Wednesday and that the fare in first class was $110 (22) and in second class $60 (12) . These Cunard ships were the first to carry the now standard white light on the bow or masthead, a green light on the starboard side and a red light on the port side. At this time service between New York and Liverpool was cancelled because several Cunard ships were being used to transport troops during the Crimean War.