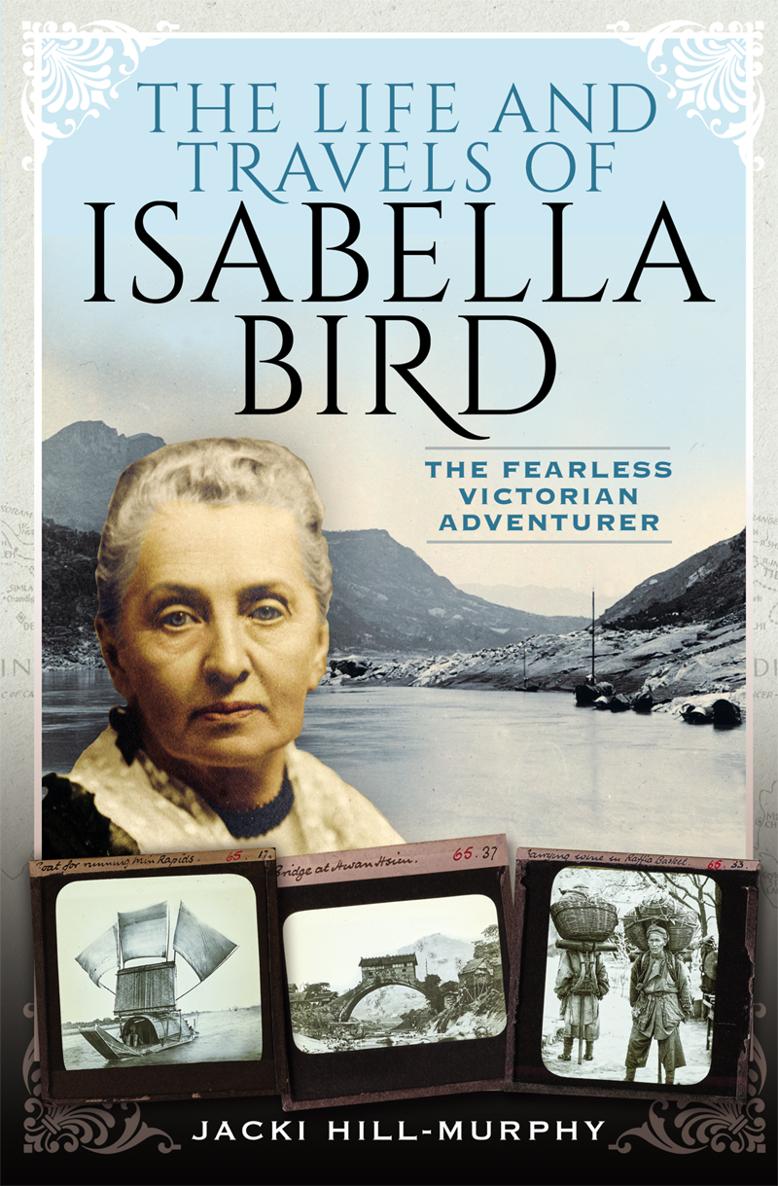

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Jacki Hill-Murphy, 2021

ISBN 978 1 52676 324 2

eISBN 978 1 52676 325 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52676 326 6

The right of Jacki Hill-Murphy to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

Isabella Bird, 4ft 11in high and dressed in a strange American riding outfit, rode into Ladakh in the Lower Himalayas in 1889, looked out at its craggy scenery and described it as a chaos of rock and sand. In her sixties by now, she was writing better than ever; her imagery erupting freely, colour splashing the pages; the mountains would be vermilion and orange and the grassy slopes of Kashmir would switch to flaming waterless plateaux of blazing red gravel as she neared the mountains of Ladakh in Lesser Tibet.

Isabella always made notes, capturing the moment amid amazing, colourful and often highly dangerous scenes, leaving us with a wealth of knowledge about Ladakh in 1889. Where better could I choose to go and follow her path? I would get to know her well by trudging across the same mountain passes, admiring the red, blue and yellow chod-tens and wide stretches of brightly coloured prayer flags that blew across the mountainous landscapes she described. So I went, living as she did in the capital, Leh, before following her trek through northern Nubra, the mountain range so evident in her book Among the Tibetans .

It was a wise decision in retrospect. I had chosen the very place where the march of progress is still limited. Globalisation is evident, but not intrusive, and while religiously following Isabellas footsteps north I became excited as what I saw matched her words, written with such fascination and novelty.

Isabella was probably the first tourist in the region and rode there on her much-admired horse, Gyalpo, passing whitewashed gonpos that rose majestically on great isolated peaks, the gate-houses to temples, reachable only by perilous rock steps to clusters of towers, courtyards and overhanging rooms seemingly floating over the landscape. The prayer flags fluttered on poles between any accessible building or rock formation, just as they do today; faded, old and tangled, and giving movement and character to the humblest backstreet.

My entry to Leh, the capital of Ladakh, lacked the romance of Isabellas. I flew in on the early-morning flight from Delhi, all ideas of taking the slow bus with a spluttering exhaust from Srinagar having been scotched by the foreign office website warning of bombs (we ignore government advice that risks voiding our travel insurance at our peril).

Isabella had other concerns than passports, visas, travel money, emergency numbers and travel insurance. These were not there to plague her; her greatest concern was the integrity of her government-approved armed guard in whose hands her safety lay. A European woman was unusual so she had been sent a soldier of the Maharajahs irregular force to be her protector. It is hard to imagine a single character throughout history less suitable to protect a lady. She described Usman Shah as looking like a stage ruffian wearing a turban of prodigious height ornamented with poppies or birds feathers. It must have been a strange sight as he walked ahead of her with this head held high, sword over his shoulder, causing Isabella great embarrassment as he plundered and beat the men they came across and terrorised the women. His job, though, came to an abrupt end on their arrival in Leh where he was recognised as a wanted murderer and arrested.

The small compound where she rested was carefully planted with European flowers and the commissioners wife brought her cups of English tea, but it wasnt long before her restful sojourn came to a sudden end. She became acquainted with the two Moravian missionariesDr Karl Marx and Dr Redsloband their wives who lived next door, and the morning after her arrival they invited her to join them on a three-week-trip over the great passes to the north to Nubra, a district full of interest and formed of the combined valleys of the Shyok and the Nubra rivers, tributaries of the Indus. This was not a journey for the faint-hearted, but she accepted with alacrity, having no idea that she would nearly lose her life.

In recreating that journey I walked over the rocky 5,450-m Digar Pass, which Isabella had followed on a yak, camping in the very same campsite in the unchanged little village of Digar with its flat-roofed mud houses amid fields of barley. I visited the great monastery of Deskyt, perched on a 2,000-ft lump of rock, that she had struggled to reach up winding stone steps, and found the lost mud house of Gergan the monk in Hundar, with its hand-painted interior and then, in the absence of a rideable yak, I walked the 80 miles back to Leh.

Our journeys were so similar, but different in one respect: the glaciers that spread down the valleys from the tops of the high passes in 1889and from which the summer melt had caused furious flooding of the Shyok River, pulling Isabella under and almost drowning herwere no longer there. This was the effect of global warming and a chilling observation in a land-locked country.

Back in Leh I hunted out Gergan, the monks great-great grandson, and he invited me into that little European garden with its rows of marigolds where I ate curry with his family. Afterwards I sat on the very patch of lawn on which Isabella had set up her tent after returning from her hard journey into Nubra, nursing the broken ribs from her neardrowning incident.