Villa of Cerreto Guidi

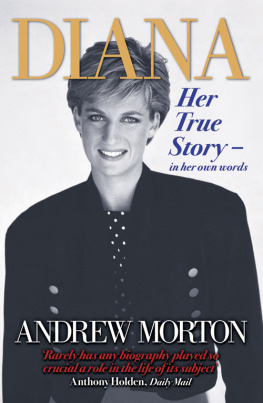

At first glance, Cerreto Guidi is not the most inviting of Tuscan towns, and certainly one of the least accessible. To reach it without personal transport is to be dependent upon an irregularly scheduled blue Fratelli Lazzi bus on the EmpoliPistoia route. The bus rattles along narrow country roads dotted with advertisements for the ubiquitous Co-op supermarkets or agriturismi farmyard bed and breakfasts. Yet another hoarding invites visitors to the Fattoria Isabella de Medici, which produces its own wine and olive oil. Its sign is adorned with a Renaissance portrait of a beautiful young woman with a generous mouth and dark hair and eyes. On arrival at Cerreto Guidi, the bus drops its passengers off at an architecturally undistinguished street corner. The town does not appear to expect many tourists; there are no Tuscan speciality shops selling panforte or cantucci e vin santo, and its only restaurant does not open for lunch. One store, for hunting gear and fishing tackle, reveals the chief pastime of Cerreto Guidis residents, and also provides a clue to the towns place in the distant past. Although much of the surrounding land is now planted with vines, if you travelled back to the sixteenth century you would find a very different Cerreto Guidi, surrounded by dense forest, home to wild boar, fallow deer and pheasants. Back then, the ruling family of Tuscany, the Medici, passed ordinances prohibiting the cutting down of trees and clearing of the woods. Deforestation might have improved the rural economy but would have spoiled the hunting, the sport that brought the Medici to this remote corner in the first place.

For the Medici, Cerreto Guidi functioned as a private country club. In 1566, Duke Cosimo I, founder of the dynasty that would rule Tuscany for two centuries, built a two-storey, seventeen-room villa up high on the site of a medieval fortress. Turn the corner from todays hunting shop and you will encounter the villas grand entrance, a cordonata: a ramped double staircase, paved in red brick, designed by the Medici court architect, Bernardo Buontalenti. Ascend the stairs, on foot rather than the horseback of the past, and you can look out from the villas terrace over the impressive stretch of terrain below. Cosimo, his sons Francesco, Ferdinando and Pietro and his daughter Isabella would ride out here from Florence, a distance of forty-two kilometres, with their retinues, servants, spouses, friends and lovers to spend a few days enjoying the thrill of the chase. As testament to the villas past, it now serves as a museum of la caccia, the hunt, replete with displays of weaponry bows and arrows, knives, flintlocks designed to pursue, slaughter and claim the local wildlife as kills.

Although games, parties and carousing were part of the entertainment, hunting was always Cerreto Guidis principal attraction, and the Medici family deemed trips here unsuccessful if it rained too hard or the sport was poor. Cosimos Isabella spent much of her life on a quest for pleasure, and she was always the first to complain if the weather at Cerreto was brutissimo, as she would say, or the game elusive. Yet such potential vexations never deterred her from pursuing a favourite pastime. In any hunting party, Isabella always held her own and more, outriding many of her male companions and claiming her own personal haul. As much a Diana in the field as an Isabella, nobody could ever accuse the princess of displaying feminine weakness. But on a trip to Cerreto on 16 July 1576, in the company of her husband, the Roman lord Paolo Giordano Orsini, Duke of Bracciano, the possibility of inclement weather and poor sport were the least of the nearly thirty-four-year-old Isabellas problems. Indeed, if she turned her thoughts at all to hunting, it might have been to ask herself what form the intended quarry was to take. Was, in fact, a human being replacing the forest fauna as prey?

Ludovico Buti, Child at a doorway

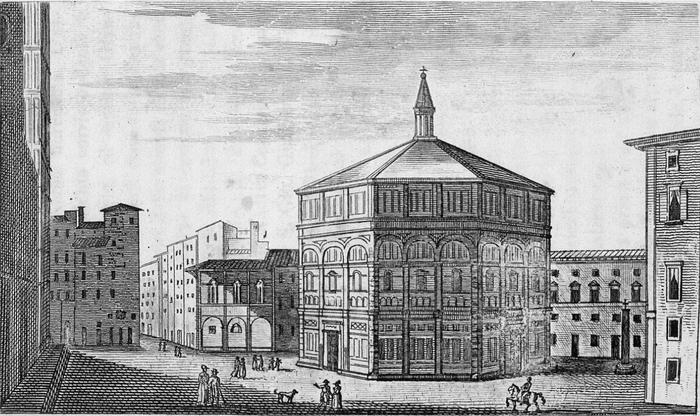

Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence

On 10 January 1542, almost thirty-four years before that day at Cerreto, the Florentine cleric Ugolino Grifoni, who served the Medici family as one of their court secretaries, was busy presenting letters to the reigning duke, Cosimo de Medici, in his chambers. The dukes wife Eleonora di Toledo was also in attendance. The ducal couple were young: Cosimo was not yet twenty-three, his wife two years his junior. As Cosimo perused his correspondence, Eleonora, who had recently announced her third pregnancy, began to vomit in such a great fashion, or I should say in such a quantity, that it seemed to me she flooded half the room, Grifoni recalled. The secretary searched for the right response to this rather unexpected interruption to proceedings. It is a sign you will bear a male child, he eventually declared. Only a baby boy could have such control over a mothers body and cause such violent illness. But, to Grifonis surprise, the duke replied to the contrary. Cosimo believed that his wife would produce a daughter.

Cosimo de Medicis response was an unconventional one because he lived in a world in which every man was supposed to expect that his wife bear him sons. A daughter would be a poor substitute. True, He had played the role of gallant lover for the first time at the age of fourteen, with a woman he referred to as my lady and for whom he bought fine handkerchiefs. At sixteen, he had fathered an illegitimate daughter, Bia, whom he adored. At the age of nineteen, when the time came for him to choose a bride, he selected the Spaniard Eleonora not purely on the grounds of political expediency, as would have been normal for a man in his position, but because he had made specific enquiries to determine that she was beautiful. He was a young man who was perfectly prepared to welcome more females into his family, and he did not perceive a daughter as little better than a consolation prize if no son was produced.