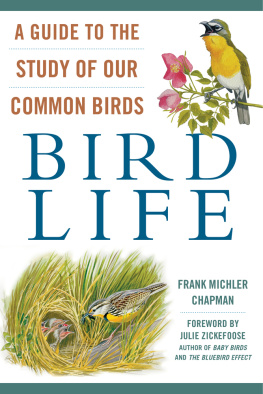

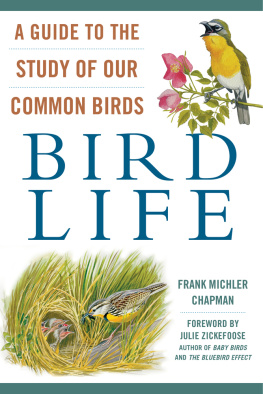

First Skyhorse Publishing edition Copyright 2018

Foreword Copyright 2018 by Julie Zickefoose

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

First published 1897 as Bird-Life by D. Appleton and Company

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

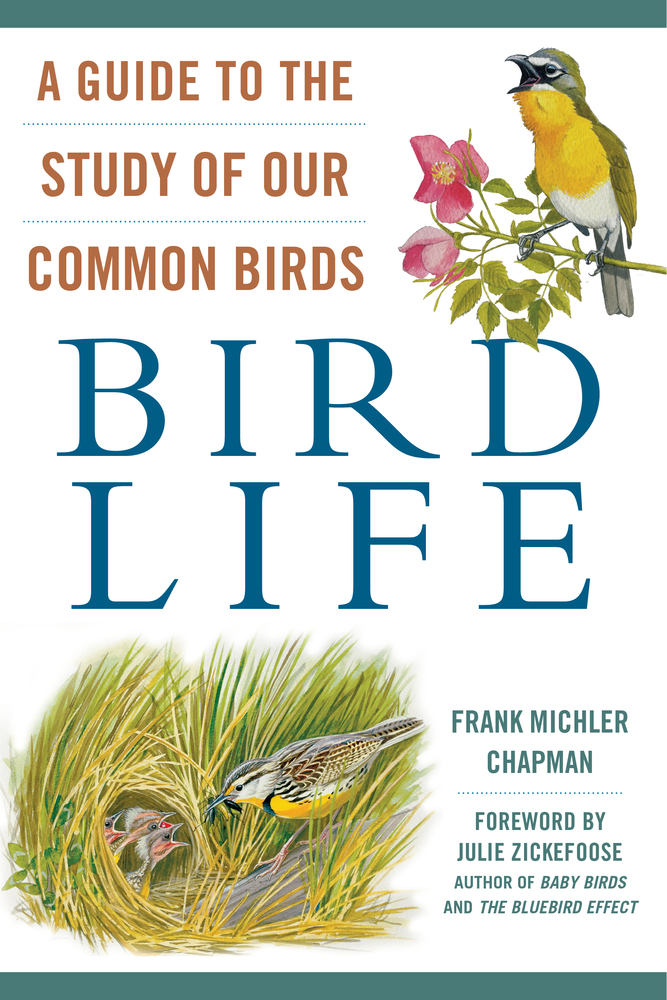

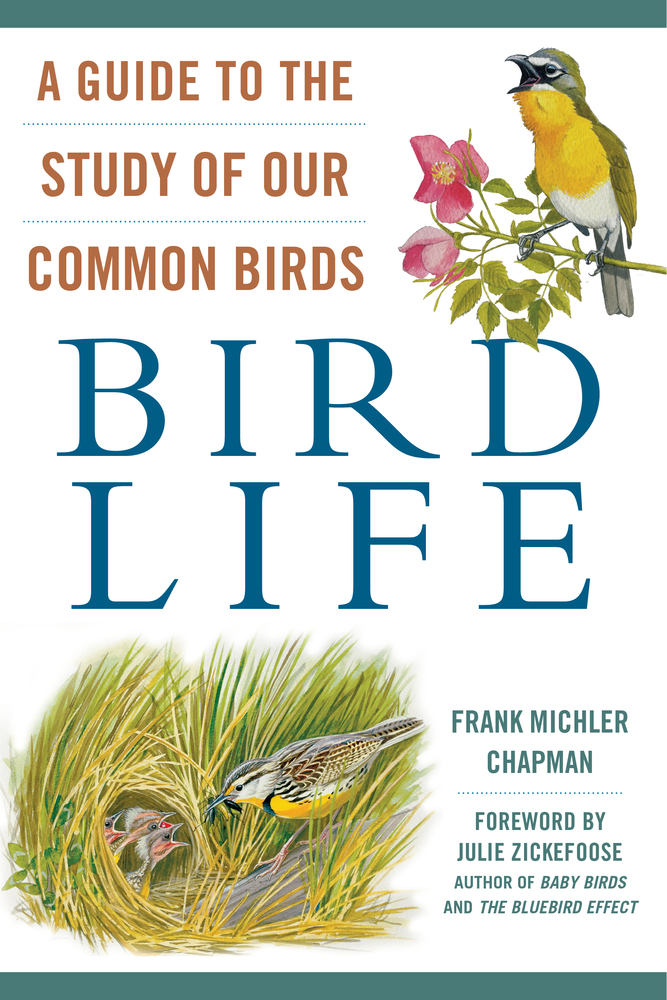

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover illustrations by Julie Zickefoose

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2448-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2450-1

Printed in the United States of America.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

He taught men to know birds; children to love them. The epitaph of the most articulate ornithologist of his generation captures the then-novel blend of ornithologist and conservationist that was Frank M. Chapman (1864-1945). Creator of the first federal bird sanctuary; originator of the Christmas Bird Count; founder of Bird Lore, later to become Audubon Magazine; and author of groundbreaking ornithological texts, Chapman was passionate about protecting the birds he studied. Often lyrical, at times quaint, at others startling, Chapmans Bird Life: A Guide to the Study of Our Common Birds invites the twenty-first century reader to contemplate how birds and bird appreciation in the eastern US have changed since 1897. Simply perusing the list of species included as common will give any birdwatcher pause, for the bobwhite, dickcissel, horned lark, vesper sparrow, and bobolink have, like the open farmland they once inhabited, now nearly vanished as resident breeders in the eastern United States. Frank Chapman describes a world that is no more. We must now travel with intent to find and observe any of these once abundant species in the East.

Bird Life was written when the much-lamented and celebrated passenger pigeon still existed, though the enormous flocks of less than fifty years ago were long gone. Yet not all of the contrasts in this important text incite wistfulness. Much in the human/avian interface has changed for the better. Gone are the days of shotgun ornithology, whereby we learned about a birds appearance and habits with the bang of a gun, dissection and examination of its stomach contents. The book is salted with observations that could have been gained in no other way, making for fascinating reading.

Throughout, our historically adversarial relationship with birds comes through in sometimes shocking ways. Herons, unprotected by any law, were shot for fun; egrets were killed for their plumes and [Bald] Eagles are becoming so rare in the Northern States that their occurrence is sometimes commented on by the local press... Nevertheless, no opportunity to kill them is neglected, and the majestic birds who in life arouse our keenest admiration are sacrificed to the wanton desire to kill.

I have often wondered why belted kingfishers, in contrast to all other kingfisher species Ive observed, take immediate flight upon approach, whether on foot or by boat; their skittishness seeming extreme and unwarranted. Here, in this passage, may lay the answer:

The Kingfisher is generally branded a fish thief and accounted a fair mark for every man with a gun and, were it not for his discretion in judging distances and knowing just when to fly, he would long ago have disappeared from the haunts of man...

In these harsh times, Chapman is an advocate for birds we now would never think of killing: Bee-keepers accuse the Kingbird of a taste for honeybees, but the examination, made by Prof. Beal, of two hundred and eighteen Kingbirds stomachs shows that the charge is unfounded.

What an image this conjures! I am glad to live in a world where the notion of shooting 218 eastern kingbirds in order to prove their innocence as honeybee predators is not only unthinkable, but laughableand illegal. So, it must be mentioned, is shooting any native non-game bird. And along with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, finally passed in 1918, the destructive attitudes Chapman so passionately fought have changed as well.

In Chapmans time, terns were still being slaughtered at their nesting colonies to be put on womens hats; Pennsylvania still paid a bounty on dead hawks. Now, tern colonies throughout New England are maintained through intensive management, and hawk enthusiasts perch by the thousands on windswept Kittatinny Ridge in eastern Pennsylvania just to watch the splendor of raptor migration, at the very spot where, until 1934, tens of thousands of these birds were brought down by sport shooters.

Other things that are looking up for todays birdwatchers: the plethora of field guides of every description, using paintings and photographs to help put a name on any mystery bird. Handy smartphone apps summon up images and sound recordings of birds, obviating the need to carry a heavy book in the field. , A Field Key to our Common Land Birds, starkly demonstrates just how far bird identification has come. This text-only key, doubtless a great boon in its time, evoked a chuckle as I scanned the categories. The key, which moved through verbal descriptions of plumage and behavior of quite dissimilar birds, unaided by any illustrations, made me wonder how anyone of Chapmans time came to know the birds, and I understood better why shotguns had been necessary for identification. Binoculars, mist nets, aluminum bands, and geotransmitters have long since replaced the shotgun as the primary tools for bird study.

In its anachronism, this book is fascinating fodder. Nearly every species account reveals changes in birds distribution, abundance, and even behavior from Chapmans time. For instance, red-headed woodpeckers are described as locally common in summer; red-bellied woodpeckers did not merit mention. Today, red-headed woodpeckers are rare and very locally-situated in the Northeast, and red-bellied woodpeckers are now common, having extended their range from the American southeast well past the Canadian border. Common nighthawks are described as nesting on the bare ground or a flat rock in open fields, and, rarely, on a house top in the city. Today, natural nighthawk nests are virtually unknown, and almost all birds have taken to nesting on flat gravel roofs in cities. Similarly, chimney swifts have utterly changed their nesting behavior since 1897. Swifts naturally nest in hollow trees or caves, and it is only in the more densely populated parts of their range that they resort to chimneys and outbuildings. Today, tree nests in chimney swifts are rare enough to merit a note in an ornithological journal. Virtually all chimney swifts have switched to using manmade chimneys.

Some species accounts are real head-scratchers. Of the northern cardinal, Chapman writes,... in spite of his bright colors, the Cardinal is a surprisingly difficult bird to see... The Cardinal is a bird of the Southern rather than the Northern states, and is rarely seen north of New York city... To one who associates it with magnolias... it seems strangely out of place amid snowy surroundings. I paused. Since when do cardinals look out of place in snow? Chapmans description of the rare, skulking southern cardinal may be attributed to the fact that this book was written before any hint of organized, regular bird feeding took hold. The massive subsidy of cardinals (not to mention red-bellied woodpeckers, tufted titmice, house finches, and Carolina wrens) with sunflower seed, peanuts, and suet has doubtless contributed to these species invasion of the Northeastern US. If one wanted to see goldfinches, Chapman recommended you devote a corner of your garden to sunflowers. This is a far cry from the continually replenished feeding stations in millions of backyards around the country. This is only one of the myriad ways in which the human/bird interface has radically changed since Chapmans time. Which, in its turn, has helped to shape avian range expansions. Humanitys influence is most of the story in changing bird distributions.

Next page