Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Rod Beemer

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.382.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951454

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.835.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Why did I rob banks? Because I enjoyed it. I loved it.

Willie Sutton, attributed

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Books are not do-it-yourself projects but require the help of many individuals and institutions. Therefore, a sincere thank-you is offered to the following: Sonya Reed, director, and Vicki Krehbiel, assistant director, of the Lane County Historical Society in Dighton, Kansas; and Laurie Oshel, assistant director at the Finney County Museum and Finney County Historical Society in Garden City, Kansas. Also thanks to the helpful staff at the Kansas State Historical Society Research RoomJessica Ditmore, Teresa Coble, Nancy Sherbert and Lisa Keysas well as Shawn Marie Stover, director, Cowley County Historical Society Museum.

Jim Maag, former president of the KBA (Kansas Bankers Association), saved me countless hours of research by sharing the index hed compiled for more than 1,200 issues of the Kansas Banker magazine. Lynne Mills and Julie Taylor at the KBA office in Topeka were also very helpful and professional.

Librarians are essential to any research endeavor, so a special thanks to Amanda Stephenson at the Hutchinson Public Library Reference Department; Toni Bressler at the Morton County Public Library; Charlene Blakeley, director, Kiowa County Public Library; and John Brubaker and Leslie Hargis at the Minneapolis Public Library.

Individuals, too, are a rich source of help and inspiration: Garden City businessman Mick Hunter introduced me to several community leaders who provided leads to stories of the Fleagle family. Margaret Symns graciously shared stories of her father, Logan H. Sanford, who was the sheriff of Stafford County before becoming the second director of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation. John W. Nixon, director of the Stockade Museum in Medicine Lodge, provided valuable and helpful information. And good friend Debra Goodrich has encouraged me to tell these stories from the first time we discussed the idea.

Most importantly, a special thanks to my wife, Dawn, who is patient and supportive of my addiction to books, and my son Chuck, who works magic with images and illustrations as well as fixing computer problems I manage to create.

If Ive failed to mention someone, its not because Im not grateful but because Im sometimes forgetful.

INTRODUCTION

Banks and bankers were not always popular and, perhaps for some, still arent. Our forefathers shared some of these same feelings. The First Bank of the United States opened in 1791, but the public had an innate distrust of banks and the banks charter wasnt renewed in 1811. For the next fifty years, banks on the expanding frontier came and went as the economy boomed and busted. Western banks sprang up almost exclusively as a response to an insufficient money supply. The problem was currency not credit. This lack of a sanctioned and stable exchange medium led to many stop-gap methods to keep the wheels of commerce grinding.

Part of the reason for this drought of currency was because people had a real, and understandable, fear that once banks became established in a community or state or country these money changers would soon control everything.

Alexander Hamilton was one of the founding fathers who saw the need for a central bank, but this idea wasnt popular with many of his peers. The bank was strongly opposed by Thomas Jefferson, who questioned its constitutionality, and James Madison, who viewed bankers as swindlers and thieves. Many in the South openly despised banks, seeing them as tools for the wealthy to take advantage of the rest of the population.

Bank distrust, and often hate, was real. As an example, Nebraska became a territory in 1854, and notwithstanding this emerging need, at that time banking still was a crime and thus punishable under the laws of the territory, as laid down in the criminal code passed by the legislature at its first session in 1855.

The first three territorial governors of Kansas were strongly anti-banking, and banking also reached criminal status in Kansas during its territorial period. Robert J. Walker commented that he would not sanction the establishment of any bank of issue in the territory, while James Deaver thought Congress did not give the states the power to charter banks, and Samuel Medary described banks as demoralizing and seductive.

Perhaps the citizens unpopular view of bankers was due to some of their practices during the early territorial days of the state:

In Lawrence, in 1857, Samuel N. Wood had a bank office in one corner of a small grocery store on Massachusetts street. There were piles of flour and bacon in the little building, Woods corner occupying about eight feet square, with a bay window in front, in which he displayed land-warrants, gold and bank-notes in a tempting manner. One day a debtor of this banker passed by in the middle of the street, being somewhat intoxicated. Mr. Wood rushed out and seized him, throwing him down and taking his pocketbook. After helping himself to the amount due him he returned the pocketbook to its place and allowed him to proceed. This was a novel, but an economical and expeditious way of making a collectionquite a contrast to the delays which creditors sometimes experience in the courts nowadays.

Banks were especially unpopular in the farm belt of the trans-Mississippi plains states during the Depression and dust bowl, when banks foreclosed on thousands of farmers and businesses.

Many of the poor people struggling to survive just didnt consider robbing banks a very serious crime.

In the first years of the depression, a typical attitude toward bank robbing was exemplified by the mother of a minor crook named George Magness. He and three friends robbed the only bank in the tiny town of Edna. Two days later they were captured near Stinnet, Texas, returned to their home county for trialWhen his mother saw her son behind bars, she became incensed and sought out Sheriff Al Coad. Looking the law officer right in the eye, the irate mother began to berate him for incarcerating her son.

Hell, sheriff, she concluded, bank robbin aint [sic] hardly no crime at all.

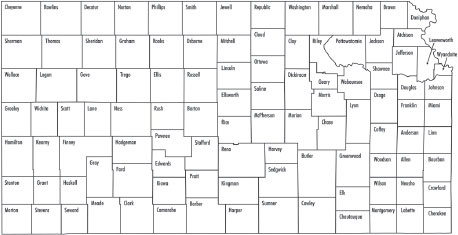

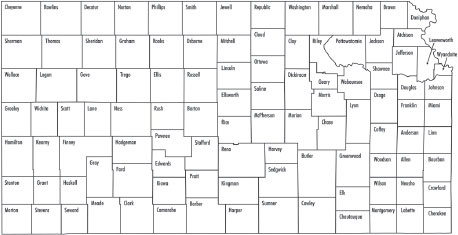

Kansas map with all counties identified. Courtesy of Chuck Beemer.

Despite the mothers feelings, robbing banks was a crime, and as with all crime, from the very beginning it has always been a contest between the good guys to develop methods of catching the bad guys who were just as earnestly seeking ways to avoid being caught.

Next page