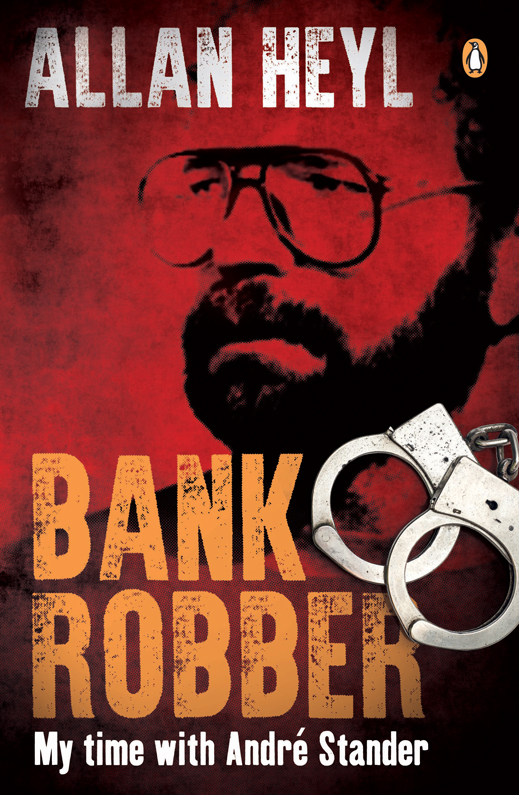

Bank Robber

Published by Penguin Books

an imprint of Penguin Random House (Pty) Ltd

Company Reg. No. 1953/000441/07

The Estuaries No. 4, Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue,

Century City, Cape Town, 7441

www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za

First published 2018

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Publication Penguin Books 2018

Text Allan Heyl 2018

Cover image Shutterstock

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: | Marlene Fryer |

MANAGING EDITOR: | Ronel Richter-Herbert |

EDITOR: | Lesley Hay-Whitton |

PROOFREADER: | Lauren Smith |

COVER DESIGN: | Sean Robertson |

TEXT DESIGN: | Ryan Africa |

TYPESETTER: | Ryan Africa |

Set in 11.5 pt on 16 pt Adobe Caslon

ISBN 978 1 77609 289 5 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77609 290 1 (ePub)

CONTENTS

Writing this book proved to be a far greater challenge than I could ever have anticipated. I would still be grappling to complete this work were it not for the constant encouragement and other forms of assistance from the many more friends than I knew I had.

I am humbly grateful for the unconditional help received from the following: Norman Clements, for your sage advice and inadvertent tutelage; Pieter Mller, for your famous humour that unfailingly lifted my spirits; the Bloemfontein Harley riders Andre du Preez, Andries Britz, Nico Odendal and Janu de Beer, for your kindness and generosity in so many ways; Helgard Mller, what a friend; Waldo van der Waal, for help out of the blue; Tracy Going and Linda Shaw, as well as several friends too coy or private to be identified: thank you, thank you. Lastly, but most definitely not least of all, to my long-suffering, thorough editor, Lesley Hay-Whitton, you are a superstar.

When I sat down to write this account of the mad spree of robberies Andr Stander and I committed from November 1983 into early 1984, I did not see us as heroic outlaws in the traditional pulp fiction sense. Sure, we were anti-establishment; sure, we were antisocial; but we were not heroes of any sort. We were just two guys driven by a desperate recklessness. I have read many accounts of our activities with disbelief, even where I supplied information. On a few occasions, I became involved in heated arguments with reputable writers and publications for disputing issues relating to Stander. I have even been threatened with violence by people whose own sense of fantasy bears no resemblance to the truth.

In 2003, the movie Stander was released. It suggested that Andr was an anti-apartheid hero, emotionally damaged by his part in shooting a black person during protests against the Nationalist government. The director of the movie, Bronwen Hughes, and I had many conversations regarding the crimes, but at no stage did she imply that she would use my input. We were simply chatting. So when the movie appeared and my name was mentioned as a source of some of the material, I saw this as a callous tactic to give authority to her movie. In unambiguous terms, I distance myself from the movie. It is a work of the imagination.

More than thirty-four years have passed since those robberies. On many occasions while revisiting the events, I paused to reflect in horror and disbelief at what we did. This book is a detailed account of what happened, not a romanticised or exaggerated version of events. It does not seek to justify or validate our activities. Nor does it offer tips and hints to would-be robbers. We could not pull off those jobs today. Bank security is now incredibly tight, which is why cash-in-transit robberies have become so prominent.

To protect many innocent people family, friends, prison inmates who were drawn into the story, I have used nicknames or initials.

Finally, it would be remiss of me not to express my deep sense of shame, embarrassment and regret for the way I allowed myself to hurtle down the slope of moral disintegration. We had become, as a woman described us, terrible people.

Monday 31 October 1983. The hour-long drive to the testing centre was proving to be far more exciting and enjoyable than I had imagined. In the months leading up to this day, I had played over a number of ways that events could unfold. But I hadnt given a moments thought to the trip from the prison to the foundry. Now, after years of walls and iron doors, I couldnt get enough of the landscape: the grazing livestock, the fields of crops, the orchards of fruit trees, farmers driving tractors and trailers. It was normal everyday life, a vision of order and certainty.

The homesteads we passed gave me a fleeting glimpse of domestic life: laundry gently flapping in the breeze, children setting off on bicycles to school, yapping dogs, small flocks of chickens and geese gathered at kitchen doors, squabbling over the feed being tossed at them. Again a vision of order and certainty.

To my surprise, these scenes left me with a profound sense of loss, regret and, yes, envy. And suddenly I was anxious about what lay ahead.

We arrived at Olifantsfontein, a sprawl of industrial buildings, and drove to a small workshop, separated from the cluster of factories by a large car park. I was alone in the back of the minibus, the two warders up front.

We were thirty minutes early and stopped facing the workshops closed door. Casually, I scanned the surroundings. I was expecting to see a car, a man, the key to my freedom. But nothing caught my eye. I tried to relax. I didnt want to alert my guardians to anything out of the ordinary. Besides, today might not be the day. It might be tomorrow.

To help calm my nerves, I resorted to that age-old nerve-settling, time-passing activity: I ate. An apple. One of the two in my days ration of two peanut-butter sandwiches, sans butter.

My munching prompted the warders to delve into their large hampers. I could tell from the aromas that they had been given boerewors, hard-boiled eggs and coffee. I ate one of my sandwiches, saving the other for lunch, in case the events unfolded later than I expected and hoped.

In the car park, vehicles came and went but nothing seemed unusual. Yet a tension was building in my stomach, in my muscles.

An elderly man in a suit and hat carrying a briefcase appeared round the building and opened the workshop door. My warders packed away their hampers.

Are you nervous, Heyl? Poeping yourself? they joked as I climbed out of the minibus.