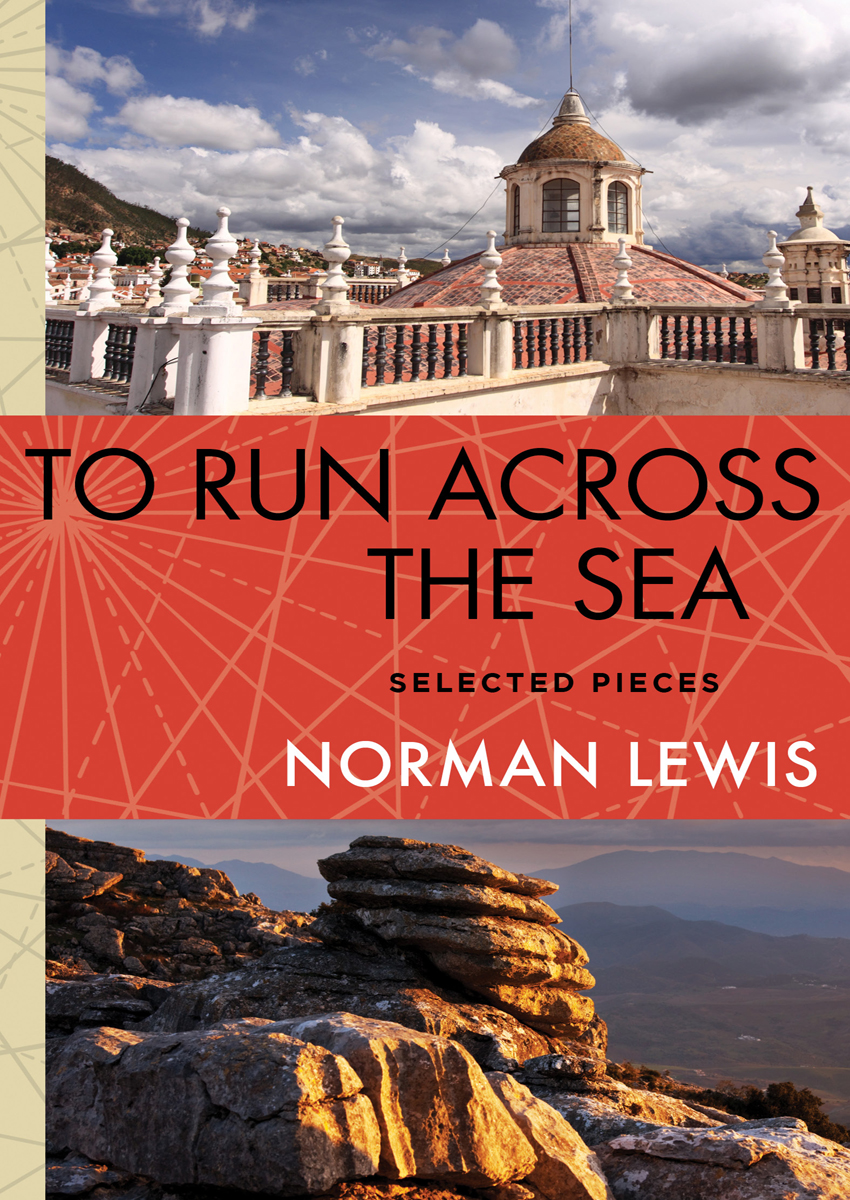

To Run Across the Sea

Norman Lewis

FOREWORD

ONCE AGAIN IN RECALLING the seductions of travel I am reminded of Evelyn Waughs glance backward at the days when, for him, the going was good. My own journeyings, launched in a slightly later period, were overshadowed by premonitions of what was to come. In 1950, with the Far East on the brink of irreversible change, it was clear that if I ever hoped to go there, not a moment was to be lost. Instinct served me well, for no one in these days, or henceforward, making the journey to Vietnam, to Cambodia, Laos or Burma will ever experience a tenth of the enchantment these countries then possessed.

When the going was good The process of the worlds impoverishment in the things that really matter to most of us rushes forward at an ever-increasing tempo, although the full extent of post-war disasters has yet to be appreciated. The greatest catastrophe has been the burning of the trees. When I went to Brazil in 1979, three million hectares of forest had gone in the previous year. One car-manufacturing firm, wishing to diversify into cattle, had started a fire, photographed by satellite, that spread through an area as large as Luxembourg. Round Manaus where I stayed, forest-clearing had become a cottage industry. Truckloads of old tyres were supplied, and with these the peasantry got the fires going. In the event the areas cleared were too small to be economically viable so they were left to become pigmy deserts. Something of the kind was happening to forests everywhere in the world.

Whether the trees were taken out by loggers, or burned down, the wildlife they contained went with them. In a single decade the number of species to become extinct exceeded that known to have been lost in the whole of the preceding century. The loss was compounded by the trade in ivory, and the growth of the market for trophies such as gorillas heads. Even worse was the spread of the sport of big-game hunting to all those who could buy a gun in developing or Third World countries. Kenya has become the graveyard of the last of the great elephant herds. Enjoy them while you can, said the guide at the sight of a herd. Youll never see them again.

You can shoot a blue sheep in Mongolia by license of the USSR government for an all-in cost of about 5,000, and several other countries issue price-lists for the elimination of similar rarities. Nevertheless, it is the protected species that attract the attention of the adventurous sportsman. To shoot a jaguar somewhere in the Amazon will run to at least 10,000. Although protected, brown bears, of which some forty to fifty survive in the mountains of northern Spain, come relatively cheap at about 4,000. The protocol of slaughter demands that the cornered animal should be tied down by stalkers, for despatch by the hunter using a spear. An inordinate fee would be demanded for the opportunity to assassinate a rhinocerosin part reclaimable by the sale of the horn (for aphrodisiac purposes), at about 2,000.

Twenty thousand or so different tribal peoples made their homes until recently in the wild places of the earth, and they are to go with the trees. Their fate, whether they like it or not, is to constitute a harvest of souls for missionary sects from the American Bible belt, carried now by the thousand in their short take-off and landing planes into every corner of the earth. They are believers in the inevitability of Armageddon, to be followed by the fiery destruction of the world from which only they and their converts will be saved. Nothing, therefore, must be allowed to stand in the way of the fundamentalist salvation, which is to be imposed at all costs, whether the recipients like it or not. The evangelists equate pleasure with sin, and will therefore have none of it. Converts must turn their backs on fun, on traditional ceremonies of any kind, on dancing, on song. They will work and pray, but laughter is to be extinguished.

If you are an amateur of primitive scenes and festivals, hunt them down and enjoy them while you can. Because they, too, like the elephant herds of Kenya, are about to vanish from the earth.

Norman Lewis, 1989

ANOTHER SPAIN

THEY CHANGE THEIR SKY, not their soul, as Horace said, who run across the sea. The sad old Roman truth is not to be refuted. Escape is never more than partial. Nevertheless, at a minor geographical level small, reviving evasions can be planned. This one was to Spain, an unlikely bolthole, it might be supposed, in the era of the package deal; yet far from the Costas in the deep interior rich lodes of undisturbed hispanidad remain to be discovered.

In preparing such an evasion simple rules are to be followed. Bring or hire a car, avoid great cities, travel by second- or third-class roads, make for the remoter parts of the south and west which are too far from anywhere to have made it worthwhile setting up industries. Here, where there has been no money to spend on development, the old Spain stubbornly survives. Rare and extraordinary flowers flourish in hedgerows that have never been reached by sprays. Towns built with the proceeds of the plunder of Moorish kingdoms, or of the Indies, remain intact. The best of them offer no accommodation for the traveller except occasionally a government parador. By way of a bonus, some of the latter are housed in grand buildings: castles, old convents, Renaissance palaces. It is normal, too, for them to be sited in areas of outstanding historic interest.

Carmona comes under this heading. It is a two days drive by the slow roads from Valencia, Alicante or Madrid. When Seville is en fteas this alluring and anachronistic town is during most of the spring and summerand there is not a bed to be had, Carmona supplies a small-scale and concentrated alternative. It is full of tremendous churches, the scent of incense, and scuttling nuns. Its window grilles, coming right down to the pavement, symbolise the Andalusian exclusion of the world from private affairs, and within the housesince shutters remain closedthe gloom Alexander Dumas noted as characteristic of these southern interiors, persists until lamps are lit or switched on at night.

Apart from palaces and churches, Carmona possesses no fewer than three Moorish fortresses, whose red walls spread a russet light through the streets like the glow beneath chestnuts in autumn leaf. Kestrels by the dozen hang pale and translucent in the sky over church towers that were once minarets, appearing like tiny kites manipulated by invisible strings. The principal fortress is the Alczar del Rey Don Pedro, favourite abode in his kingdom of Pedro the Cruel. From what is now the parador this fearsome monarchonly to be recognised in his disguise by the clicking of his arthritic kneesstole out at night to pick a quarrel with and assassinate any defenceless subject who happened to be abroad. It was here in 1492 while awaiting the fall of Granada that Ferdinand and Isabella sat side by side on their thrones to hand down the ferocious edicts by which the conquered territories were to be governed. This was a bad time to be on the losing side. King Ferdinand the Saint, whose self-imposed penances brought about his own death by dropsy and starvation, converted the Muslim survivors in this town after its conquest. Magnanimous by the standards of his day he spared those who turned promptly to Christ. Where conversion was proved later to have been insincere, backsliders were burned in batches, the king himself frequently applying the torch to the faggots after first implanting the kiss of forgiveness upon the cheeks of those about to suffer.