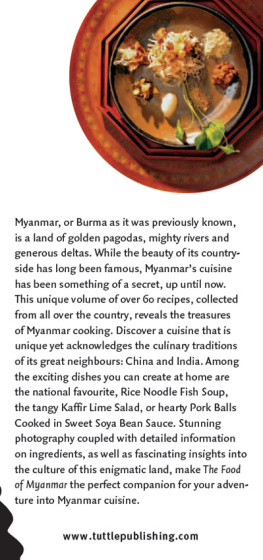

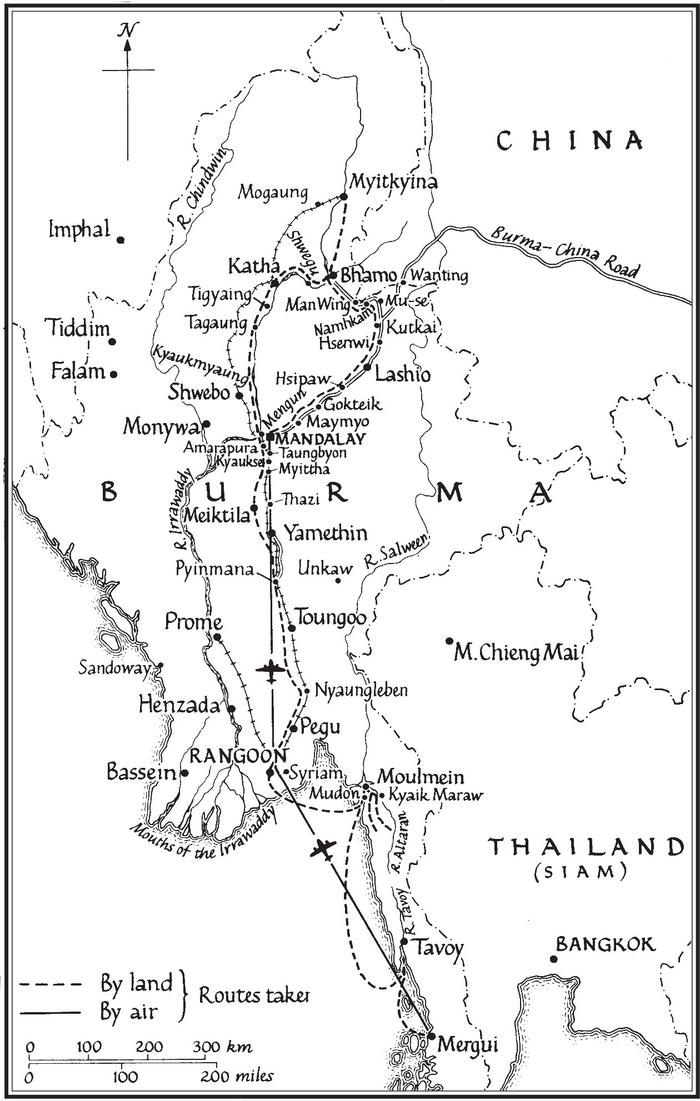

I N 1949, with the creation of the Peoples Republic of China, that country became as remote and inaccessible as Tibet had been of old. I believed that this policy of self-isolation might spread to neighbouring countries and, having determined to see before I died something of the Far East, I went in 1950 to Indo-China, and covered a little of the area still open to travel in that fabulous country. In that year there was no slackening in the rate at which the Far Eastern lands were passing beyond the reach of the literary sightseer. Korea was scorched off the map, and if we were embroiled with China, said the observers, the flames of this conflagration might spread to Burma where Communist guerrillas were already firmly entrenched. One of two things would then happen: either the country would pass with China behind what had been called the Bamboo Curtain, or it would be defended by the West, as Korea had been defended, and with similar results. In either case the traditional Burma, with its archaic and charming way of life, would have vanished.

In a rational plan for seeing a little of the Eastern world these grave considerations seemed to me to entitle Burma to priority. Accordingly I flew there at the beginning of 1951.

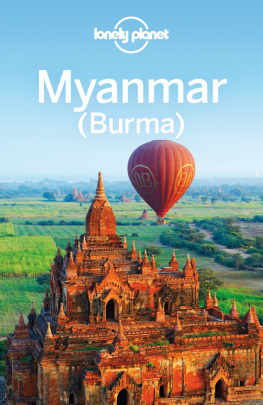

B URMA SPREAD as a dark stain into the midnight sea. Soon the inert grey of water lifted to the horizon, but the darkness that followed it was sprinkled with points of light. There was a bleared reflection from broad waterways of the wasting moon; the blinking of lamps strung out in lines, leading weblike to the centre of some unseen city; then the banal reality of that accepted wonder of the air-travellers world, the Shwedagon Pagoda by night. The moonlight was too weak to reveal the pagodas golden surfaces, and as it was late most of the artificial illumination had been switched off. What remained was a deserted fairground at midnight a few trivial pendants of lights which sketched in, without revealing, the august shape.

At the airport, the bleak, palely lit buildings, where lines of passengers awaited their interrogation by innumerable officials, were decorated, as if by design, by groups of tiny, silk-clad, elfin creatures unmistakably adult, since some nursed at the breast exquisite miniatures of themselves. And while the dreary procession of sleepwalkers dragged by from official to official, from bureau to bureau, the little silken groups sat comfortably apart, faces impeccably powdered, hair garlanded, hands in lap, watching us with unblinking eyes, no evidence of relish, and only the occasional ejaculation of a stream of betel. There seemed no answer to the riddle of their presence. They were there when first we staggered into the building and still there, squatting silent and motionless in unchanged positions, when, hours later, as it seemed, the bus took us away. Of Mingaladon Airport it could at least be said that it did not suffer from the cosmopolitan insipidity natural to airports. Here one was bathed in the essence of the country while waiting to pass through the formalities.

* * *

I awoke next morning feeling dazed and queasy. There had been an earthquake in the small hours the first of any importance, the papers said, since that of 1931 but although half awakened I had put the sensation down to a mild heart attack, or some manifestation of overtiredness, and immediately dropped off again. Now I was aroused once more by an unfamiliar clamour. Outside the window was a courtyard , and mynas were using it for their exercises, giving out shrill, bubbling cries, indistinguishable from the gurglings of those pipes which are filled with water and used to imitate bird-sounds. There were crows as well; fine, glossy, Asiatic specimens, not very large, but very sprightly, their shoulders splashed with a blue iridescence. They were extremely noisy in their affable crow-like way. Above their endless cawings could sometimes be heard a shrill kitten-like mew. This came from a kite perched on a wireless aerial. It was useless to hope for more sleep.

In any case, there was a knock on the door and a smart young Indian page appeared and handed me a card on which was printed, U Maung Lat, Ex-Head Master. Further enquiries from the boy produced nothing better than nods and smiles, so reluctantly I dressed and went down. U Maung Lat, who was sitting in the lounge, rose to greet me. He had the manner of a savant and was dressed conservatively, wearing a hand-tied turban, and the frayed jacket of the impecunious man of letters. Smiling gently, he produced a newspaper cutting which said that among the passengers to arrive on that mornings plane had been the author Lewis Morgan. The police, he said, had been able, from their records, to direct him to my hotel. It is one of the accepted humiliations of the writer that, however simple his name, no one can ever get it right. In my travels in Indo-China I had been given an identification paper describing me as Louis Norman, writer, commissioned by Jonathan Cape Limited of Thirty Bedford Square. By a slow process of compression and corruption I finished this journey as Monsieur Thirsty Bedford; which, as the name and description had been recopied about twenty times, I did not think unreasonable. But on the present occasion, having written out my name in full perhaps a dozen times within the past few hours, I found the distortion less pardonable.

However, U Maung Lats smile was irresistible. Mr Morgan, he said, coming straight to the point, I have decided my wish to place upon your shoulders the responsibility of publishing my treatise, amounting to ninety-four thousand words, on those three things for which Burma is of all countries the most famous. The three things, said my visitor, were snake charming, the playing of rattan football, and the destruction of the invading forces sent by a Ming Emperor of China. This, his lifetimes work he said, had been accepted, during the Japanese occupation, by the Domei Agency, but, alas, through subsequent events beyond their control, they had been unable to fulfil their contract.

Many other new arrivals in Rangoon, I have no doubt, must have met this charming eccentric, but on me this delightful piece of oriental dottiness, gleaned from my first non-official contact in Burma, had a tonic effect. Immediately the irritations of the night before vanished. I was full of hope for the future.

* * *

Rangoon, even in temporary decline, is imperial and rectilinear. It was built by a people who refused compromise with the East, and has wide, straight, shadeless streets, with much solid bank-architecture of vaguely Grecian inspiration. In the town one is constantly being taken back to Leadenhall Street; while down on the Rangoon river-front the style is that of the London Customs House. Within these edifices, there is something ecclesiastical in the gleaming of dark woods and brass. In passing over these thresholds the voice is instinctively hushed. There is much faade and presence, little pretence at comfort, and no surrender to the climate. This was the Victorian colonisers response to the unsubstantial glories of Mandalay.

These massive columns now rise with shabby dignity from the tangle of scavenging dogs and sprawling, ragged bodies at their base. In recent years, the main thoroughfares, with such resolutely English names as Commissioners Road, have acquired a squalid incrustation of stalls and barracks, and through these European arteries now courses pure oriental blood. Down by the port it is an Indian settlement. Over to the west the Chinese have moved in with their outdoor theatres and joss-houses. The Burmese, in their own capital city, content themselves with the suburbs. Little has been done by the new authority to check the encroaching squalor. Side lanes are piled with stinking refuse which mounts up quicker than the dogs and crows can dispose of it. The covers have been taken off most of the drains and not replaced. Half-starved Indians lie dying in the sunshine. Occasionally insurgents cut off the towns water supply. There are small annual epidemics of cholera and smallpox, and the incidence of bubonic plague is unlikely to decrease because the sewers of Rangoon swarm with rats, which it is irreligious, according to all Burmese and most Indians, to kill. Even when the rats have been caught alive in traps, to what end it is not clear, they have actually been released by the pious, who were ready to rise earlier than the rat-catchers, if spiritual merit could thereby be earned. Wherever there is a vacant space the authorities have allowed refugees to put up pestiferous shacks, which now flank in unbroken lines the country roads leading into Rangoon, the railway tracks, and the shores of the Royal Lake.