CHAPTER 1

MY FATHER-IN-LAW, ERNESTO CORVAJA, although Sicilian by birth, was obsessively concerned with all matters pertaining to Spain. His family originally came from there, which was evident from their name, and there was said to be evidence to prove that an ancestor had been included in the suite of the viceroy Caracciolo, sent from Spain to Sicily following its conquest.

In his London house Ernesto still nourished the ghost of a Spanish environment with a housekeeper recruited from some sad Andalusian village who glided silently from room to room wearing a skirt reaching to her ankles, and kept the house saturated with the odour of frying saffron. Despite Ernestos agnosticism, a Spanish priest in exile was called in to bless the table on the days of religious feasts, and although Ernestos son Eugene resisted his fathers efforts to send him to Spain to complete his studies, his daughter, Ernestina, briefly to be my wife, had agreed to spend a year in a college in Seville.

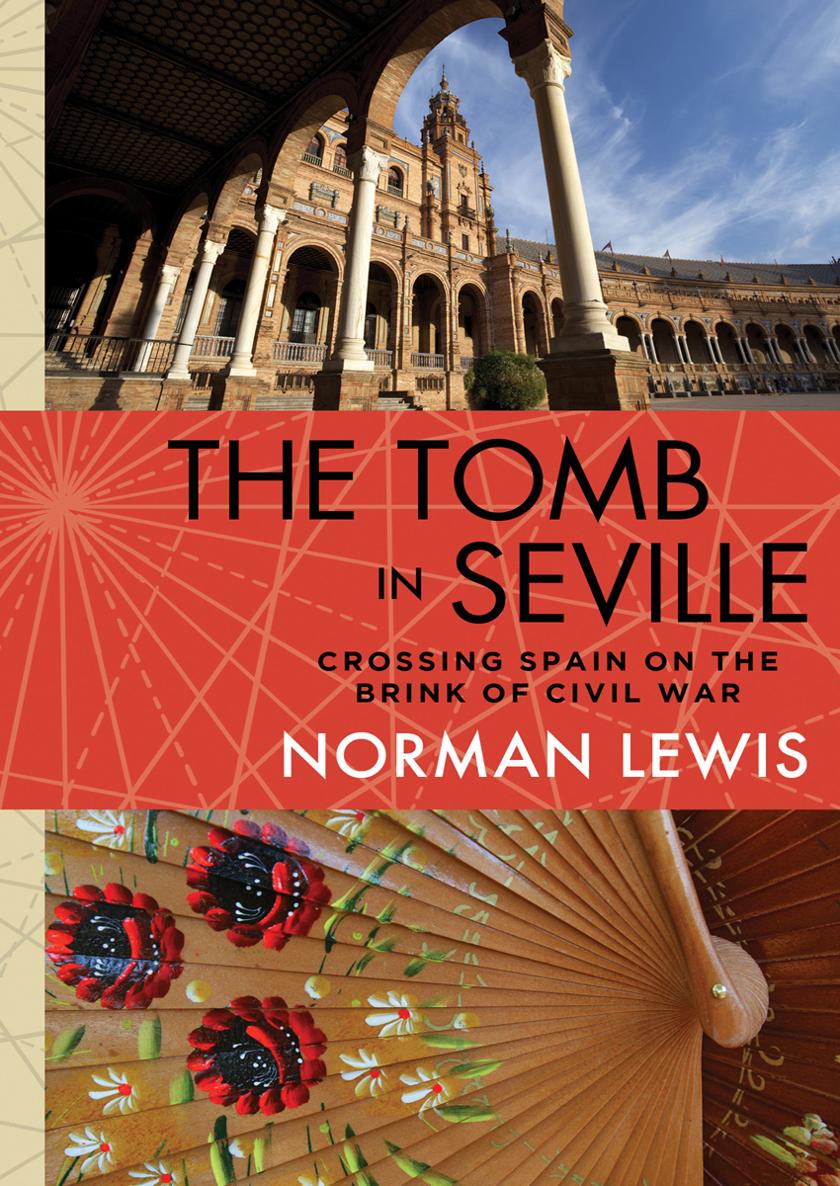

Visits to Spain had taken on the nature of quasi-religious pilgrimages in this household, and Eugenes resistance was finally overcome by his fathers offer to pay the expenses both of my brother-in-law and myself for a visit of two months to Seville. Here we could inspect the remains of the old so-called Corvaja Palace, pay our respects at the family tomb in the cathedral, and discover if any memory, however faint, had survived of the Corvajas in the ancient capital of Andalusia.

Our Spanish travels, it was decided, would begin at San Sebastin, just across the countrys north-western frontier with France, thereafter following a slightly more circuitous approach to Seville, through the less developed and, to us, more interesting areas, including in the west, for example, the towns of Salamanca and Valladolid.

On Sunday 23 September 1934 we attempted to book seats on the train for San Sebastin, only to be told at the London ticket office that bookings could be made only as far as Irun on the French frontier with Spain. Here a temporary interruption of the traffic was expected to be rectified next day.

At Irun some twenty hours later, we found the frontier closed and the air buzzing with rumours; several Spanish passengers showed signs of alarm. Nevertheless those with tickets for Salamanca were given accommodation in a small but excellent local hotel, and a guide was provided to show us round a somewhat unexciting town. In the morning, entry into Spain had been restored and we boarded a train which carried us through to San Sebastin in just over a half-hour.

In a way the hold-up at the frontier had been interesting for us, providing an instant and striking demonstration of the contrasts in style and character of the two peoples involved. Irun was full of alert and energetic Frenchmen and women who made no concession to the southern climate, rose early to plunge into their daily tasks, ate and drank sparingly at midday and in the early evening, foregathered socially thereafter for an hour or two before retiring to a splendid coffee-scented bar. This, we were to discover, was the diametric opposite of the Spanish way of life. The French lived in a kind of nervous activity. They hastened from one engagement to another with an eye kept on their enormous clocks.

To arrive in San Sebastin, a few miles across the frontier, was to be plunged into a different world. This was a town of white walls guarding the privacy of its citizens, all such surfaces being covered with huge political graffiti. No one was in a hurry, or carried a parcel, and here there were no clocks. Iruns restaurants filled for the midday meal at 12.30 p.m. and emptied one hour later, when their patrons returned to their offices or shops. Those of San Sebastin admitted their first customers at 2 p.m., and these would have spent an absolute minimum of an hour and a half over the meal before vacating their tables. The majority then returned home for a siesta of an hour or so before tackling their afternoons work.

How long do you suppose well be staying? Eugene asked.

Well, two or three days, Id say. What do you think? Its more interesting than I expected. I was talking to the chap who does the rooms. San Sebastin is famous for its paseos apparently. You know what a paseo is?

Well, more or less.

Most old-fashioned towns have one. Here they have twoa popular version for the working class in the early evening and a select one, as they call it, for the better people later on. I read somewhere they havent scrapped the piropo here.

The what?

The piropo. The habit of shouting sexually offensive remarks at good-looking women in the paseoor even in the street. The dictator Primo de Rivera put a stop to it, but its crept back into favour again in places like this.

Right then, said Eugene, lets make it three days.

The Royalty Hotel seemed to reflect the old style of life, and was full of what Eugene described as bowing and scraping.

What comes after this? he wanted to know.

Well, Burgos I suppose. Nice comfortable distance. About seventy or eighty miles. With a good car we could do it in the morning, or carry on to Valladolid which sounds more interesting. Pity nothings said about the state of the roads.

Theyll be able to tell us at the hotel, Im sure.

The four-course dinner took us by surprise, but we did our best with the huge portions. Eugene went off to give Ernesto a surprise phone call, but came back shaking his head. No lines through to England at the moment, he said. The people in the hotel all seemed surprised.

Later that day Eugene received a surprise request from the woman who had waited on us at table, and had received our compliments in the matters of service and food with obvious pleasure. Her request was that one or the other of us would escort her in the first paseo that evening. Such was the prestige in San Sebastin, she explained, of foreign visitors from the north, that to appear in public with one infallibly enhanced a local girls status. Dorotea was both pretty and exceedingly charming, so her request was immediately granted. Eugene provided a splendid bouquet and we then spent the hour and a half of the paseo strolling girl in arm in the company of several hundred local citizens in the formal gardens by the sea.

The paseo was accepted as health-giving, rejuvenating exercise. More importantly, for the traveller out of his depth in foreign surroundings and reduced to constant apology and confusion imposed by the loss of language, it was a godsend. Whether merchant, soldier or minister of religion, the paseo smoothed out all the problems. The mere act of walking in the company of beaming strangers provoked a change of mood. Within minutes of joining a paseos ranks the beginner had shaken hands with everyone in sighta cordial gripping of fists sometimes strong enough to produce a moistening of the eyes. The leaflet we collected as new members of the friendly walk advised us that one should always smile, but laugh with caution. A number of actions came under its ban: At all times refrain from shouting or whistling. Gestures with the fingers are to be avoided. Do not wink, do not turn your back on a bore in an ostentatious manner, and, above all, never spit.