W HEN I WAS FIRST pushed by my mother into the presence of my Aunt Polly, the bandages had only been removed from her face a few days before to expose a patchwork of skin, pink and white, glazed in some places and matt-surfaced in others, dependent upon the areas of thighs or buttocks from which it had been stripped to cover her burns. The fire had reached every part of her and she spoke in a harsh whisper that I could hardly understand. She had difficulty in closing her eyes. Later I found that sometimes while asleep the lids would snap open. It was impossible to judge whether or not I was welcome because the grey stripe of mouth provided by plastic surgery in its infancy could hold no expression. She bent down stiffly to proffer a cheek and, prodded by my mother, I reached up to select a smooth surface among the puckerings, the ridges and the nests of tiny wrinkles, and touch it with my lips.

In the rear, the second aunt, Annie, wearing long white gloves, holding a fan like a white feather duster, and dressed as if for her wedding, waited smilingly. I was soon to learn that the smile was one that nothing could efface.

Dodging in and out of a door at the back of the hallway, the third aunt, Li, seemed like a startled animal. She was weeping silently, and with these tears I would soon become familiar. I was nine years of age, and the adults peopling my world seemed on the whole irrational, but it was an irrationality I had come to accept as the norm. My father, who wanted to be an artist, and failing that a preacher, had been banished to England following irreconcilable personality clashes with my grandfather who feared and disliked such manifestations of the human spirit. Now, after years of an aggrieved silence, there were to be attempts to rebuild bridges. It was my grandfathers ambition to make a Welshman of me, so my mother had brought me to this vast house, with little preparation, telling me that I was to live among these strangers for whom I was to show respect, even love, for an unspecified period of time. The prospect troubled me, but like an Arab child stuffed with the resignation of his religion, I soon learned to accept this new twist in the direction of my life, and the sounds of incessant laughter and grief soon lost all significance, became commonplace and thus passed without notice.

My mother, bastion of wisdom and fountainhead of truth in my universe, had gone, her flexible maternal authority replaced by the disciplines of my fire-scarred Aunt Polly, an epileptic who had suffered at least one fit per day since the age of fourteen, in the course of which she had fallen once from a window, once into a river and twice into the fire. Every day, usually in the afternoons, she staged an unconscious drama, when she rushed screaming from room to room, sometimes bloodied by a fall, and once leaving a menstrual splash on the highly polished floor. It was hard to decide whether she liked or disliked me, because she extended a tyranny in small ways to all who had dealings with her. In my case she issued a stream of whispered edicts relating to such matters as politeness, punctuality and personal cleanliness, and by being scrupulous in their observance I found that we got along together fairly well. I scored marks with her by mastery of the tedious and lengthy collects I was obliged to learn for recitation at Sunday school. When I showed myself as word perfect in one of these it was easy to believe that she was doing her best to smile, as she probably did when I accompanied her in my thin and wheedling treble in one of her harmonium recitals of such favourite hymns as Through the Night of Doubt and Sorrow.

Smiling Aunt Annie, who counted for very little in the household, and who seemed hardly to notice my presence, loved to dress up, and spent an hour or two every day doing this. Sometimes she would come on the scene attired like Queen Mary in a hat like a dragoons shako, and other times she would be a female cossack with cartridge pockets and high boots. Once, when later I went to school, and became very sensitive to the opinions of my school-friends, she waylaid me, to my consternation, on my way home got up as a Spanish dancer in a frilled blouse and skirt, and a high comb stuck into her untidy grey hair.

Li, youngest of the aunts, was poles apart from either sister. She and Polly had not spoken to each other for years, and occupied downstairs rooms at opposite ends of the house, while Annie made her headquarters in the room separating them, and when necessary transmitted curt messages from one to the other.

My grandfather, whom I saw only at weekends, for he worked in his business every day until eight or nine, filled every corner of the house with his deep, competitive voice, and the cigar-smoke aroma of his personality. At this time he had been a widower for twenty-five years; a man with the face of his day, a prow of a nose, bulging eyes, and an Assyrian beard, who saw himself close to God, with whom he sometimes conversed in a loud and familiar voice largely on financial matters.

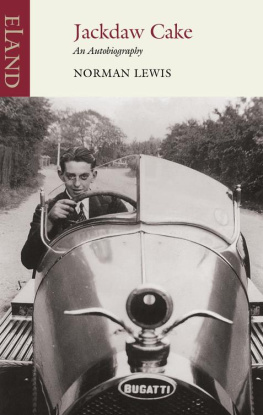

A single magnificent coup had raised him to take his place among the eleven leading citizens of Carmarthen, with a house in Wellfield Road. It was the purchase of a cargo of ruined tea from a ship sunk in Swansea harbour, which he laundered, packaged in bags dangerously imprinted with the Royal crest, and sold off at a profit of several thousand percent to village shops and remote farming communities scattered through the hills. This had bought him a house full of clocks and mirrors, with teak doors, a wine cellar, and a wide staircase garnished with wooden angels and lamps. After that he was to possess a French modiste as his mistress, the towns first Model T Ford, and a valuable grey parrot named Prydeyn after a hero of the Mabinogion, too old by the time of my arrival to talk, but which could still, as it hung from a curtain rod in the drawing room, produce in its throat a passable imitation of a small, squeaking fart.

My grandfather had started life as plain David Lewis but, swept along on the tide of saline tea, he followed the example of the neighbours in his select street and got himself a double-barrelled name, becoming David Warren Lewis. He put a crest on his notepaper and worked steadily at his family tree, pushing the first of our ancestors back further and further into history until they became contemporary with King Howel Dda. For a brief moment the world was at his feet. He had even been invited to London to shake the flabby hand of Edward VII. But on the home front his life fell apart. The three daughters he had kept at home were dotty, a fourth got into trouble and had to be exported to Canada to marry a settler who had advertised for a wife, and the fifth, Lalla, an artist of sorts, who had escaped him to marry a school teacher called Bennett, and settled in Cardiff, was spoken of as eccentric.

This was Welsh Wales, full of ugly chapels, of hidden money, psalm-singing and rain. The hills all round were striped and patched with small bleak fields, with the sheep seen from our house as small as lice cropping the coarse grass, and seas of bracken pouring down the slopes to hurl themselves against the walls of the town. In autumn it rained every day. The water burst through the banks of the reservoir on top of Pen-lan, sent a wave full of fish down Wellfield Road, and then, spilling the fish everywhere through Waterloo Terrace, down to the market. What impressed me most were the jackdaws and the snails on which the jackdaws largely lived. The snails were of every colour, curled and striped like little turbans in blue, pink, green and yellow, and it was hard to walk down the garden path without crushing them underfoot. There were thousands of jackdaws everywhere in the town, and our garden was always full of them. Sensing that my mad aunts presented no danger, they were completely tame. They would tap on the windows to be let into the house and go hopping from room to room in search of scraps.