An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

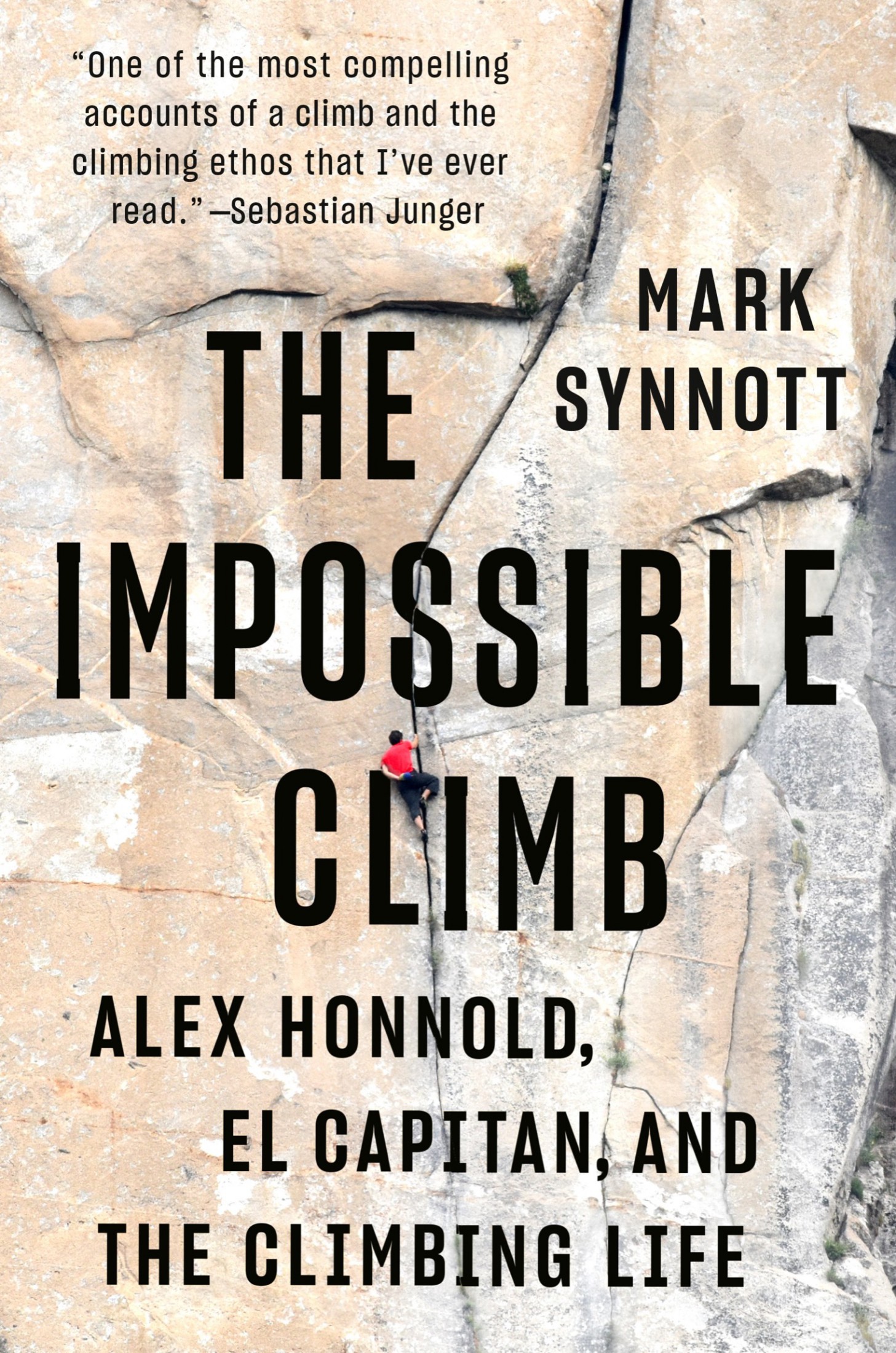

Copyright 2018 by Mark Synnott

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

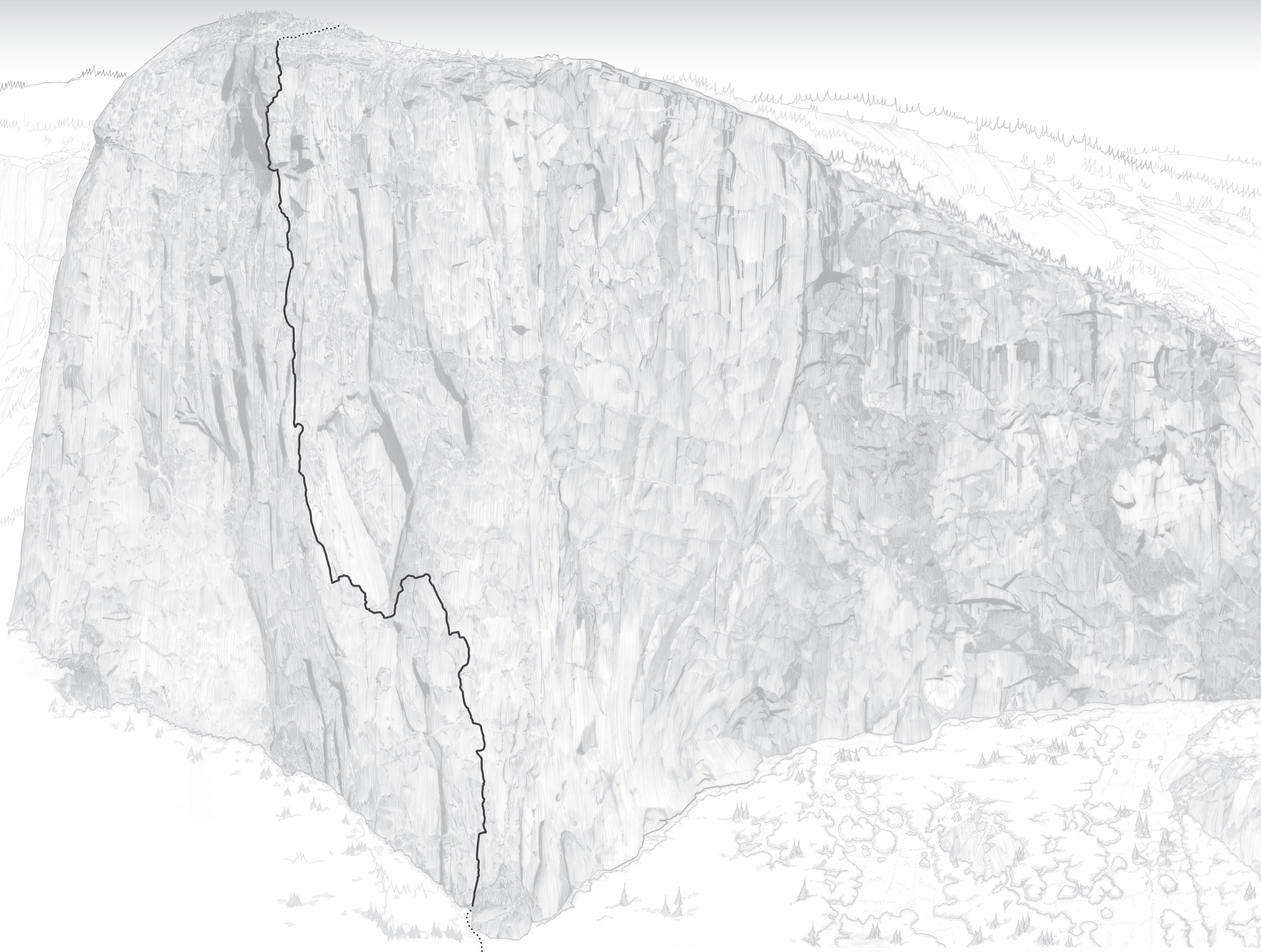

by Clay Waldman, climbingmaps.com

Photograph on of Cathedral Ledge Peter Doucette

Photograph on of Great Trango Mark Synnott

Photograph on of El Capitan Christian George

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

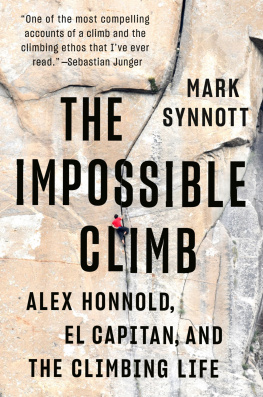

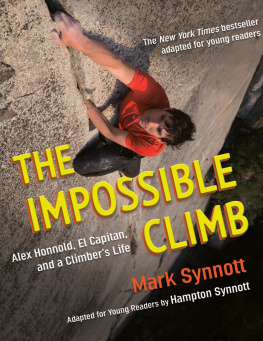

Names: Synnott, Mark, author.

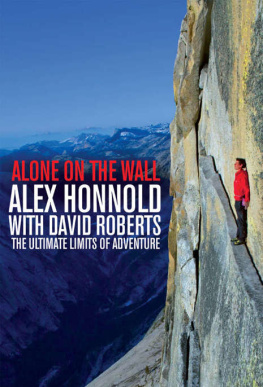

Title: The impossible climb : Alex Honnold, El Capitan, and the Climbing Life / Mark Synnott.

Description: New York, New York : Dutton, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007271 | ISBN 9781101986646 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101986653 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Honnold, Alex. | MountaineersUnited StatesBiography. | Free climbingCaliforniaEl Capitan.

Classification: LCC GV199.92.H67 S96 2018 | DDC 796.522092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007271

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_2

For

Tommy,

Lilla,

Matt,

Will, and

Hampton

CONTENTS

Prologue

The Ditch, as climbers sometimes call Yosemite Valley, typically remains summer hot well into September, but a rogue cold front had blown in overnight. A wan sun slouched low to the east, barely discernible through a thick, overcast sky. Tiny droplets of water saturated the air. Alex wondered, Is the rock getting slippery? The friction still felt okay, probably because a stiff breeze was drying the stone as quickly as the moisture-laden air was wetting it. But the rock had absorbed the raw gray cold, and that was starting to bother his feet. His toes were a little numb, and the size 42 shoes felt sloppy on the glacier-polished granite. He wished hed worn the 41s.

Years earlier, when he first contemplated free soloing El Capitan, Alex had made a list of all the crux sections on Freerider, the parts that would require careful study and extensive rehearsal. The traverse to Round Table Ledge, the Enduro Corner, the Boulder Problem, the downclimb into the Monster, and the slab section on pitch 6, six hundred feet off the deck, which he now confronted. Of all the various cruxes on the 3,000-foot-high route, this one haunted him most, and for a simple reason: Its a friction climb that is entirely devoid of grips on which to pull or stand. Like walking up glass, thought Alex.

He couldnt help thinking about the fact that it had spit him off before. Its only rated 5.11, which, while still expert-level climbing, is three grades below Alexs maximum of 5.14. But unlike the overhanging limestone routes in Morocco that Alex could bully into submission by cracking his knuckles on the positively shaped holds, the crux here required trusting everything to a type of foothold called a smear. As the name implies, a smear involves pasting the sticky-rubber shoe sole against the rock. Whether the shoe sticks depends on many factors, including, critically, the angle at which it presses the rock. The best angle is found by canting ones body out away from the wall as far as possible without toppling over backward. This weights the foot more perpendicular to the stone, generating the most friction available. The more a climber can relax, the better a smear feels. Conversely, a tense or timid climber instinctively leans in toward the rock, questing for a nonexistent purchase with the hands. To rely solely on such a delicate balance between the necessary adhesion and teetering past the tipping point in a high-consequence situation is perhaps the most dreaded move a rock climber can encounter.

Alex had climbed this section of El Cap twenty times and fallen once on this move. A guy who keeps numerical records of every climb he has done since high school, he had noted to himself in recent days that 5 percent of his attempts at this move had gone awry. And those were low-consequence situations; he had worn a rope clipped to a bolt two feet below his waist.

He had obsessed about free soloing El Capitan for nine years, nearly a third of his life. By now he had analyzed every possible angle. Some things are so cool, theyre worth risking it all, he had told me in Morocco. This was the last big free solo on his list, and if he could pull it off, perhaps he might start winding things down, maybe get married, start a family, spend more time working on his foundation. He loved life and had no intention of dying young, going out in a blaze of glory. And so one in twenty wasnt going to cut it. He needed to get this move, along with the other crux sections, as close to 100 percent as possible.

But Alex wasnt thinking any of this. He had trained himself not to let his mind wander when he was on the rock. He was famous, after all, for his ability to put fear in a box and set it on an out-of-the-way shelf in the back of his mind. The life questions, the analyseshe saved that stuff for when he was hanging out in his van, hiking, or riding his bike. At that moment, he was just having fun and not thinking about anything except climbing and climbing well.

Details, whether they rose to the surface of his mind or not, did factor into the climbing equation he was in the midst of solving: how he wasnt sure how his right foot felt because his big toe was slightly numb, or how the callus on the tip of his left index finger seemed glassy on the cold rock, or that his peripheral vision, key for picking up all the subtle ripples and depressions in the rock, diminished when he had his hood up, as he did now.

Back in the 1960s, when this section of El Cap was pioneered, the first ascensionist drilled a quarter-inch hole in the rock here, hammered in an expansion bolt, clipped an trier to it, and stood up in this stirrup to reach past the blankness. That bolt (since replaced with a much beefier three-eighths-inch stainless steel version) was still right here, next to Alexs ankle.

Balancing on his left foot, Alex lifted his right leg high and squeegeed his toe onto the blank seventy-five-degree-angle rock. Trusting more than feeling the friction, he rocked the full weight of his body onto this smear.