Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Dana, who made me promise to just do my best.

And for Sam and Sylvie. Youre just as old as we were then, but youre too young to read this book.

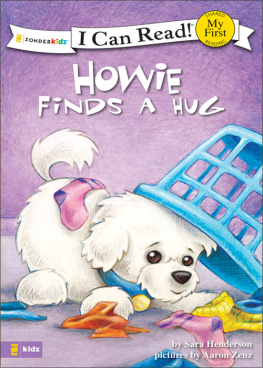

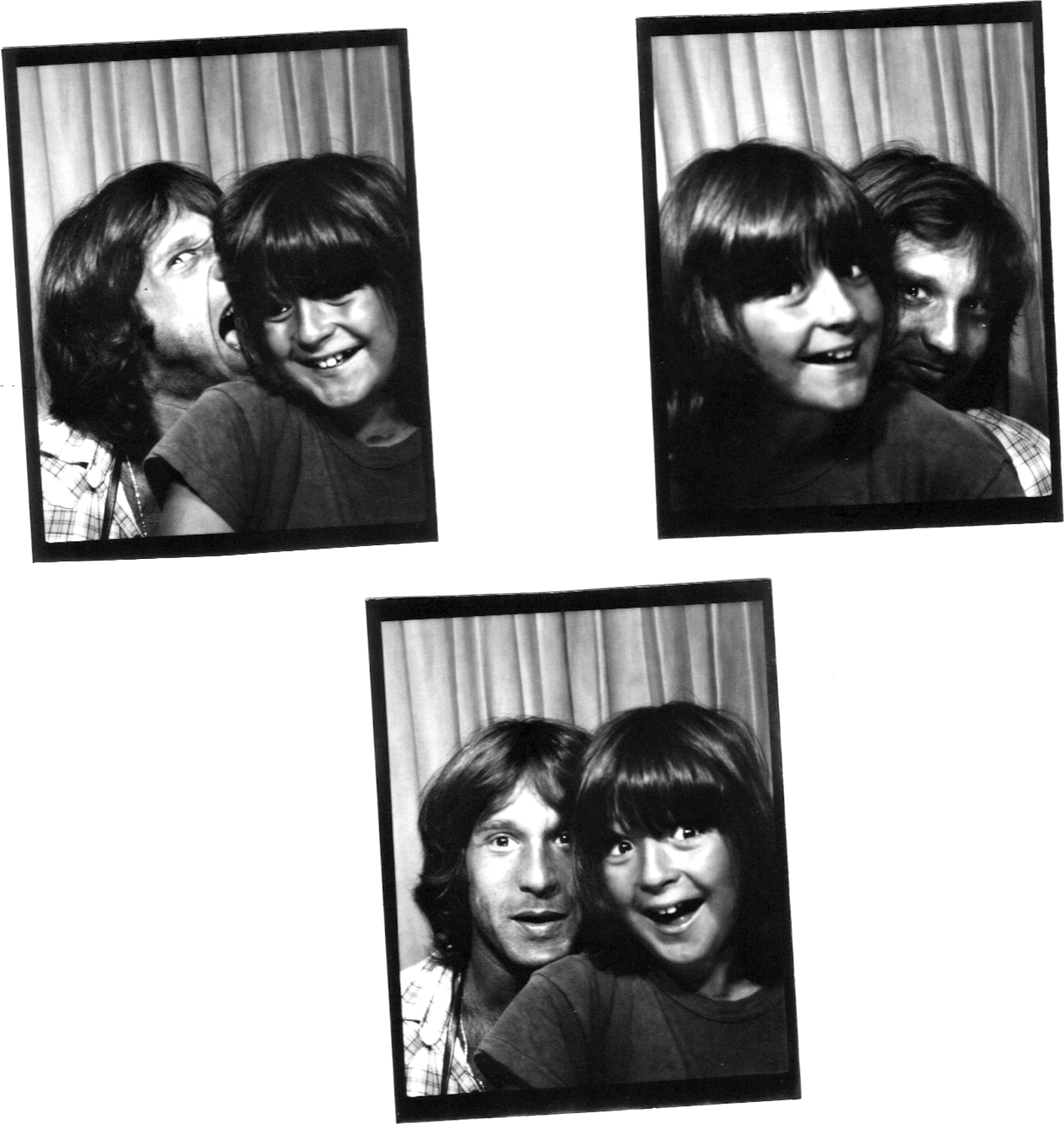

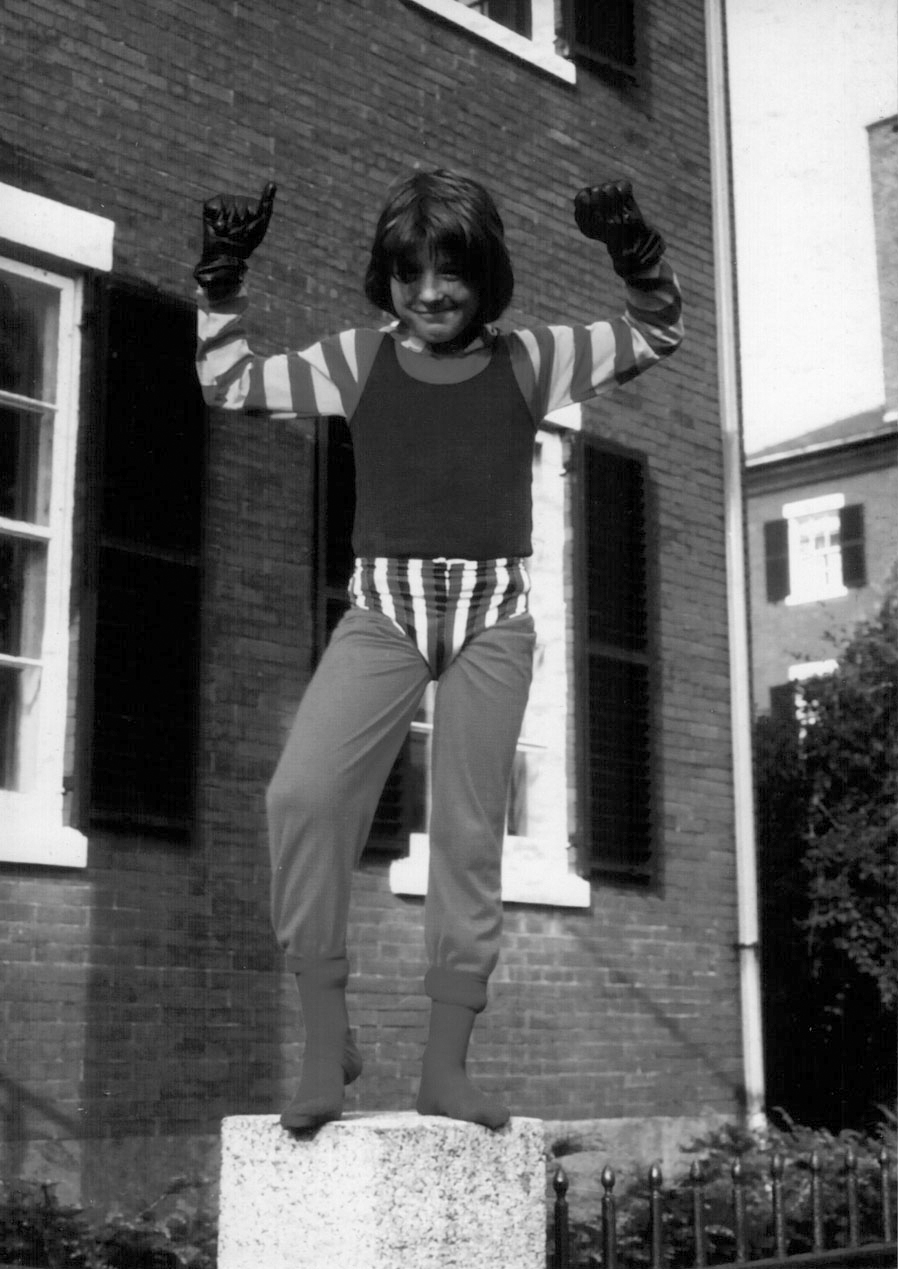

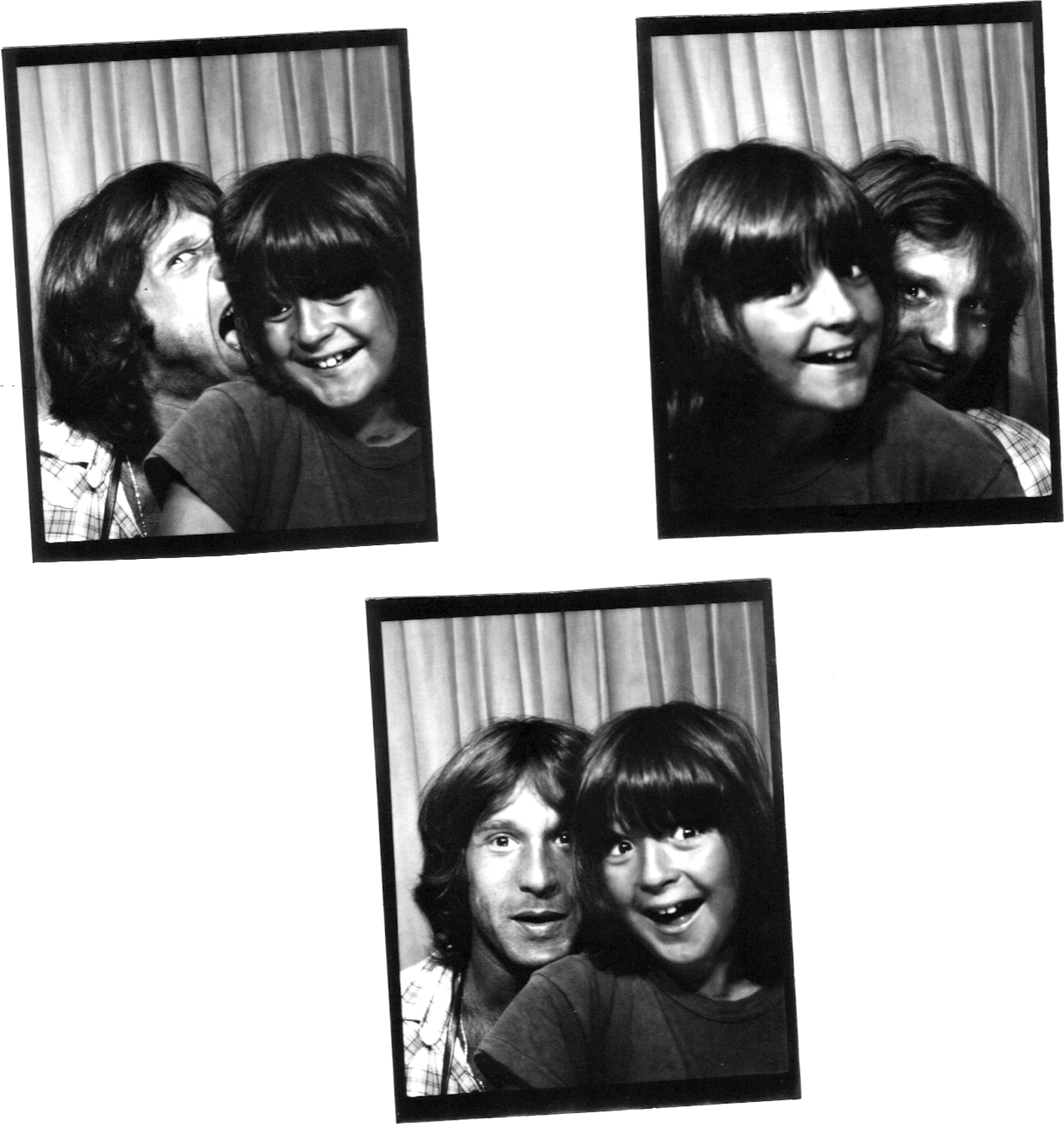

Howie and me, 1978

It contributes greatly towards a mans moral and intellectual health, to be brought into habits of companionship with individuals unlike himself, who care little for his pursuits, and whose sphere and abilities he must go out of himself to appreciate There was one man, especially, the observation of whose character gave me a new idea of talent.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

If Im going to be Starsky, then youre going to have to be my Hutch.

Howie Gordon

What the hell are we doing in Salem? The town famous for torching neighbors who seemed anything other than Puritan. Were not just strangers, were Jews! Sure, were unobservant, noncomformist, freethinking New York Jews in paisley-patched dungareesbut still, were so very Other, and so very wandering. Nice to meet you, Salem, Massachusetts. Well be gone soon.

Its our eighth move in twelve years, but none of the first seven were nearly as bleak. Everything about Salem is different than Manhattan, right from the break of day. No noise. No cars. No life until the Salem dads emerge from their front doors, suited up and shuffling to the train for the slow weekday ride to Boston. They are followed by the sockless, Docksider-wearing sea-captain wannabes, unshaven and still bleary from the rum scrum of the night before. They buy fresh bread and weak coffee at the Athens Bakery, drag on long brown cigarettes on their way to their boats or their private painting studios, avoiding the gaze of the dudes cruising rusty Camaros and booming Jethro Tull and Black Sabbath, gunning for their morning dogs hair at the Pigs Eye.

But on Sunday mornings these streets are empty. I ride alone.

I deliver papers, and not that well. At six thirty each Sunday my alarm buzzes and a fresh pile of North Shore Sunday s, bound with wire and wrapped in plastic, waits for me on the front steps.

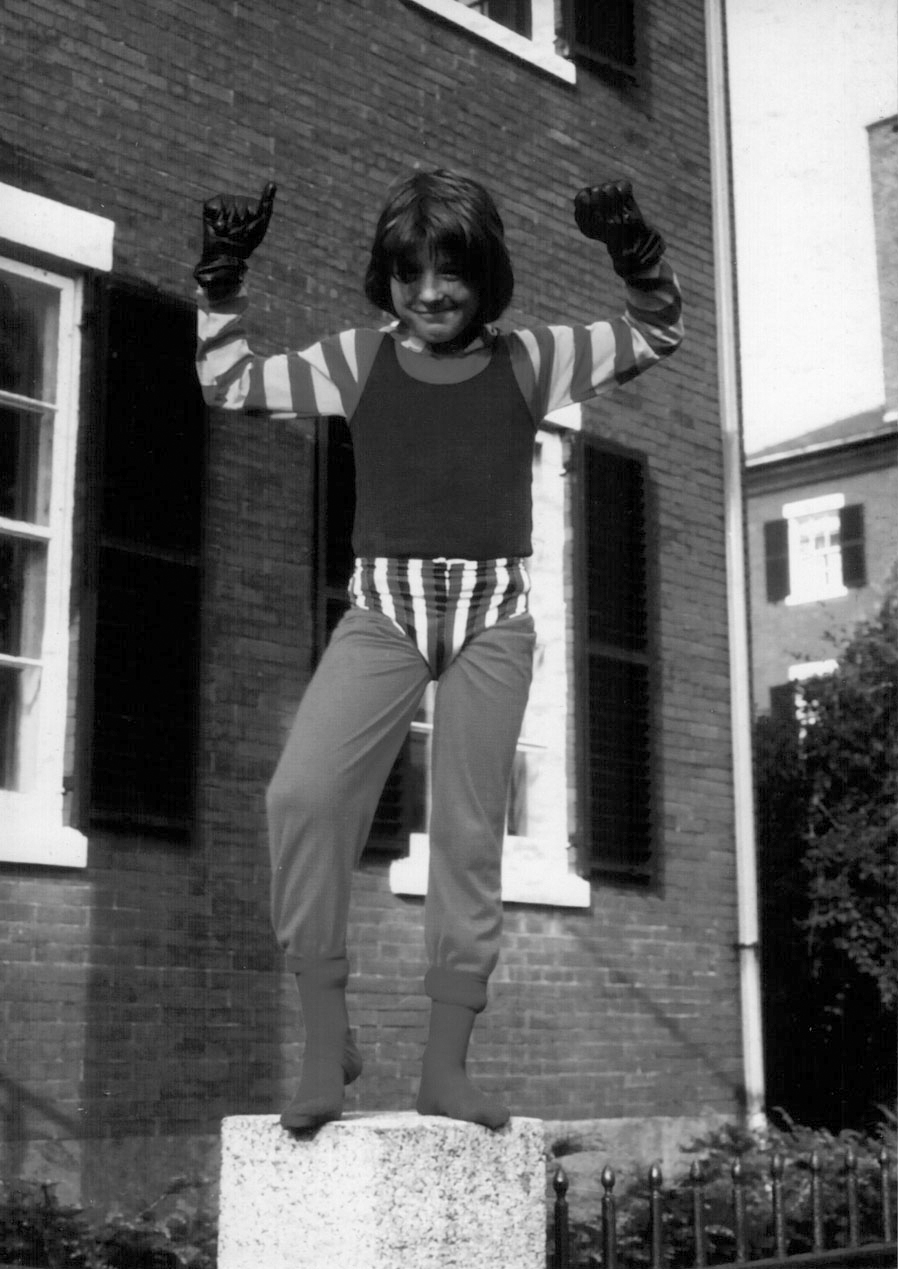

I grab a T-shirt, the striped jeans I wore yesterday, a Marblehead zip sweatshirt and my canvas paper bag. Atjeh, our dog, is still settled by the foot of my bed in the same Sunday rhythm reserved for the rest of the Cove family. Her black lids rise wearily when I open the door, ice-blue eyes indifferent.

The North Shore Sunday has just enough original content to merit being called a newspaper, but its otherwise filled with advertisements for the butcher sale at the A&P, marine supplies, and cordwood delivery. People dont pay for itthe only person who seems to care if it shows up is Mr. Getchell, my route supervisorbut I still try to get tips for delivering it when I can.

Outside, it looks as if the cold mist might give way. I snip the rigid newspaper bindings with the wire-cutter crotch of my pliers. The news of the week is a mix of global import and local fluff. The Vatican denies foul play but refuses to conduct an autopsy on Pope John Paul I. The Marblehead Squirts hockey team made the cover after a visit to Quebec. Peter Frampton is still recovering from his car accident. I fill the stiff paperboy bag with my burden. I hate this. Every part of it. Waking up early, balancing as I ride, the sack cutting into my shoulder like a claw, rolling through the haunted streets alone, forced into neighborhoods that smell like damp ashtrays. I rarely finish the job, and now towers of undelivered papers teeter in my closet and sop up rabbit tinkle in Bunny Yabbas wooden crate in the center of my room. The first few weeks, I threw maybe twenty or thirty copies in there. Just the last couple of streets worth. As the weather got colder I started quitting the route three-quarters of the way in. Then halfway.

I shamble out back, where my Apollo waits by a rosebush. Its a Ross, five-speed, stout, rugged tires, whitewalls, chrome fenders, banana seat, and Easy Rider handlebars. The saving grace of any paper route morning.

This is the eighth time Ive had to move. Eighth! Mama and Papa keep trying to convince us that moving to Salem is a great achievement, the realization of a long-held dream to return to the place of their youth, the North Shore of Massachusettsand to do so in spectacular fashion. Mamawho grew up nearby in Lynn, Lynn, the city of sin, you never come out the way you went inspent months shopping for a house in Marblehead. Thats the next town over from Salem, where Papa grew up and where his parents, Grandma Wini and Grandpa Sam, still live. Weve ended up just a few miles away from them, and thats really the only good thing I can say about leaving our apartment on West End Avenue in New York.

It needs to be something historical. Something old, Mama had said over the phone to the Realtor, who couldnt produce anything close to my parents price range in the dense clapboard cluster of houses along Marbleheads sparkling harbor.

Would you consider living in Salem? the Realtor had asked as Mama calculated mortgage rates on a piece of pink scrap paper.

Theres only one street I would consider living on in Salem and thats Chestnut Street, she answered, believing this wasnt an option.

Well, then you better come and see this house.

Its the most beautiful street in America, Mama told us. And Im not the only one who feels that way.

Apparently it was true because Papa had said the same thing over the phone to me when he heard that Mama was going to look at 31 Chestnut. Its the most beautiful street in America, he said cheerily. Magazine worthy. Youll see.

Who says that? I asked Mama, wondering what was so bad about the first street we lived on. Or the fourth. Or the seventh. Who says its the most beautiful? And why do we need to live somewhere beautiful? Riverside Park is beautiful. So was Washington, D.C. And Westport, Connecticut. And New York the first time around.

It is, said Mama, and it smells like someone peed all over it. This is a better place to grow up. Youll see.

Our house is one of three brick homes pressed into one, side by sidea gift from a Salem sea merchant to his three daughters. Our part, the left third of the manor, has three sprawling floors, all of which show their age. Seventy-three-hundred square feet! Papa never tires of proclaiming, whatever that means. There are seven bedrooms, five bathrooms, a haunted attic, and an entire apartment hidden behind an unlocked swinging door in the disproportionately small galley kitchen.

My sister, Amanda, and I run the length of the house when we first arrive, through not one but two living rooms, craning to see the dust bunnies and dead flies caught in the cobwebs dangling from the impossibly high ceilings. There are fireplaces in nearly every room, and a gigantic basement, once the servants kitchen, with a wooden dumbwaiter at one end. It could still be used to transport toys and snacks (but NO kids!) to the little kitchen above by way of a thick, oily rope worn smooth by decades of calloused hands sending dishes and meals up and down. Every room shows its age, wallpaper drooping and bubbled, signs of water recently dribbled from under the crown moldings and ceiling medallions, and fractures in all the wood floors which promise legendary splinters.