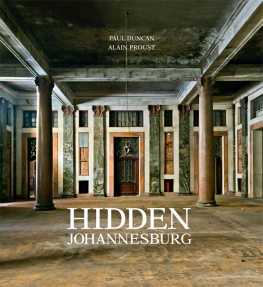

Published in 2016 by Struik Lifestyle

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Company Reg. No 1966/003153/07

The Estuaries, 4 Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue, Century City 7441, Cape Town

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.randomstruik.co.za

Copyright in published edition: Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd 2016

Copyright in text: Paul Duncan 2016

Copyright in photographs: Alain Proust 2016

ISBN 978 177007 992 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, digital, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and the copyright owner(s).

Publisher: Linda de Villiers

Managing editor: Cecilia Barfield

Design manager: Beverley Dodd

Designer: Helen Henn

Editor: Gill Gordon

Proofreader: Cecilia Barfield

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Mary Armour, Imam Ibrahim Atasoy, James Ball, Flo Bird, Father George Coconas, Duan Coetzee, Michael Collins, Puneet Dhamija, Dominique Enthoven, Dick Glanville, Susan Greig, David Hart, Rabbi Ilan Hermann, Eric Itzkin, Craig Kaplan, Russell Kaplan, Skye Korck, Ruth Kuper, Reshma Lakha-Singh, Robert Long, Saleh Mayet, Barbara McGregor, Gavin McInnes, Brian McKechnie, Gussie Nourse, Phetsile Nxumalo, Catherine Page, David Pickard, Jo-Marie Rabe, Kalim Rajab, Alayne Reesberg, Warren Siebrits, Beverley Smith, Michael Spicer, Jacques Stoltz, Ernst Swanepoel, Sim Tshabalala, Julia Twigg, Neil Viljoen, Sarah Welham.

The View

CONTENTS

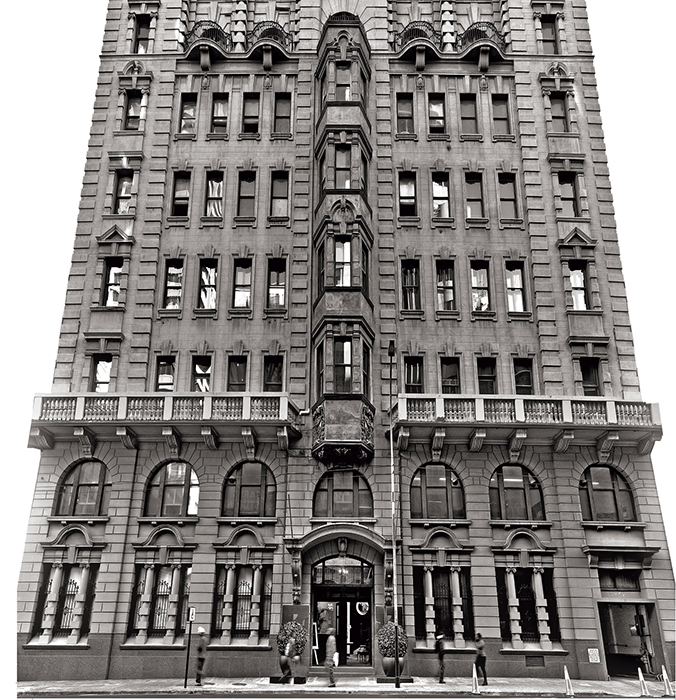

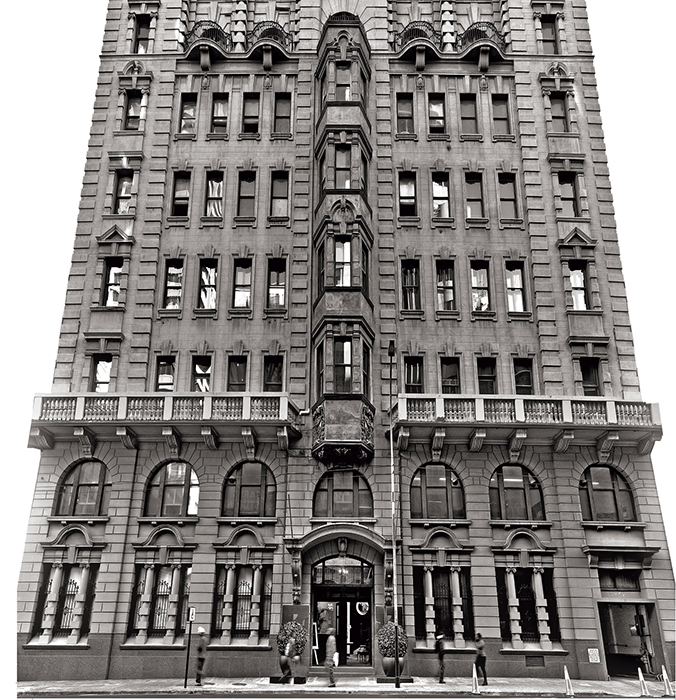

The entrance faade of Leck & Emleys Corner House is characterized by a copper-clad projecting central bay.

INTRODUCTION

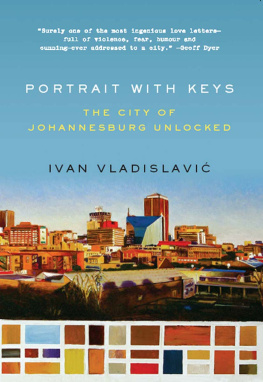

T here is always way more to see when you explore a city on foot, keeping to the pavements, crossing its streets from side to side, and making detours to catch a glimpse of something overlooked previously, or to take a short cut. Suddenly, you become aware of looming faades, their adornments, the detail, door cases and windows, roofscapes, symmetry, scale, monumentality, light and shade in fact, all those things that give buildings their presence and underpin their contexts and their place in the world. And theres that constant question asked more out of curiosity than from any particular concern: what does the inside look like? If theres an interesting faade theres probably an even more fascinating interior. And if the exterior is intact, whats happened inside? Whats the story behind how this particular building came to stand here and play a role in a city plonked down and grown like some hybrid maverick in the hot African veld?

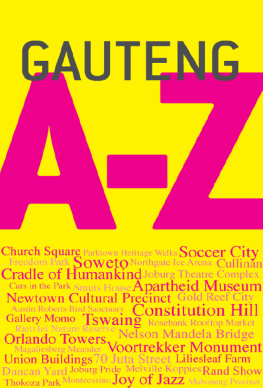

Johannesburg old Johannesburg is no exception to any of this. It may be difficult now to be a pedestrian (try it though; I did) in the CBD and the old suburbs nearby, like Hillbrow or Doornfontein, other than on an organized tour, but in other places Newtown for example, and lately, Braamfontein theres been a revival of cultural and mercantile life leading to a revitalizing of neighbourhoods and an almost dizzying injection of activity thats woken them from near-death experiences.

But Johannesburg is a city that only truly reveals itself when you look upwards on the outside anyway. Not only are there plenty of magisterial faades festooned with a wealth of detail, much of it preserved because its out of reach, but also there, writ large, is a plausible visual microcosm of Western architecture between the two last decades of the nineteenth century and those at the middle of the twentieth. Much of it apes its peers in sophisticated, fashionable European metropolises like London or Berlin or Paris, or American cities like New York or Chicago. That such a new city was able to do this so quickly hints at its resources both financial and physical. They had the cash to do it, and the spacious land. Look at the Rand Club: a puffed-up building with three different street faades, on a site where, not 20 years before it was built, there had been just open veld. Much of early Johannesburg, including the Rand Club, went through successive waves of building construction as the earliest wooden shacks and corrugated iron-roofed shanties were transformed into more permanent, two- or three-storey brick-and-mortar structures with cast-iron verandahs templated out of a catalogue in the Victorian style, only to be replaced by statelier buildings that, indicating a mature city at full throttle, ran the gamut of late nineteenth century and early twentieth century architectural styles from fin de sicle to beaux arts, Arts and Crafts to neoclassical, designed by architects who had distinguished themselves either in Cape Town or in the offices of well-known, even famous, British practices.

Most often, and from the close of the Anglo-Boer War, Johannesburgs buildings are an architectural representation of British imperial hegemony; City Hall for example, or the buildings of Herbert Baker that today seem to be extraordinarily non-indigenous white elephants in territories far from home. Bakers picturesque country houses, like Northwards and Glenshiel, spring to mind, until you look closely and notice that they respond to their environments both functionally and respectfully. And sometimes, here and there, you stumble on a building thats transitional; not yet distanced enough from that old world and still tentatively embracing a new global language, like Gordon Leiths Freemasons Hall. Now and again there are buildings that are in tune with, even herald, a brave new world and are revolutionary; Leck & Emleys Corner House is the best example of this. Most often, they just ape the fashion of the day and are first-class examples of sparkling new styles of design, interpreting international optimism with attention to local needs or bullishness. Johannesburgs Art Deco buildings fall into this category and there are some remarkable survivors of the period, like Gleneagles apartment block in Killarney, and Ansteys Building, on the corner of Jeppe and Joubert Streets in the CBD. Sometimes theyre part of an attempt to inculcate into the cityscape a national architectural style as in the building boom of the 1930s. Leith, again, is a key protagonist, along with Gerard Moerdijk, their opus in this respect being their work in association as the architects of Park Station.

Johannesburg is filled with hidden treasure. And while this, the Chassidic Synagogue, formally known as the Chassidim Shul or Chabad House, in Yeoville, doesnt actually feature in this book, its a remarkable find in an unremarkable neighbourhood, its facings in terrazzo the work of local sculptor Edoardo Villa.

Im making very broad sweeps here. But a walk around the CBD is like finding yourself in a labyrinthine textbook discovering or uncovering signs and symbols and, learning to read them, being enabled to understand ever more the contexts of the city and its history. Its an uplifting experience simply because so much of early Johannesburg is still there, even though business has mostly moved on to places like Sandton, leaving these old neighbourhoods and their monuments in decline. The CBD is key in this respect, as are Hillbrow and Doornfontein. And while Hidden Johannesburg looks at a variety of buildings in those areas, it also reaches into Parktown, Westcliff and further afield, into Killarney, Kew, Orange Grove, Linksfield Ridge, Victory Park and Orchards. Names barely able to do justice to the evolution of these streets and suburbs.

Next page