Introduction

This book is a collection of case studies about the precarity of everyday life in Johannesburg. It is made up of chapters based on case studies that document peoples practices of help-seeking, care, support and healing in response to their everyday insecurity. Throughout the book, the authors describe a state of ontological insecurity that manifests itself in economic, spiritual, psychological and physical ways and, perhaps most importantly, refuses neat distinctions between these categories. However, alongside this sense of insecurity is an equally strong sense of optimism, care and a striving for change. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that this book deals very centrally with themes of the struggle for progress, mobility (geographic, material and spiritual) and a sense of possibility and change associated with Johannesburg. This book is, therefore, about precarious life in the city of Johannesburg and peoples responses to it.

The context for the case studies is the complex political reality of post-apartheid South Africa, a country emerging from the repression of apartheid and the violence leading up to and through the period of transition to democracy. In the popular imagination, the South African transition to democracy was celebrated throughout the world as one that was emblematic of a peaceful, negotiated settlement following a protracted period of violent conflict. South Africas period of violent political conflict, leading up to democracy in 1994, captured the worlds attention (Habib & Desai, ).

However, in the 20 years since democracy, people in South Africa have had to deal with the impact of the apartheid past as they struggle to cope with the continued, deeply alienating, inequalities and deprivations that have persisted since its formal demise (see Hamber, ).

Perhaps the fault line that was most obviously neglected during South Africas political transition was that of economic inequality. Fairly soon after the TRC, Posel and Simpson ().

In addition to economic inequality, South Africa remains known for its high levels of violence even as this violence is recast as criminal rather than political violence (see Cohen, ).

South Africa has also seen ongoing violence shaped by enduring racial hierarchies such as the murders of black farm workers by their employers. For example, in 2003, farmer Gerrit Maritz dragged Jotham Mandlazi, a worker on his farm, behind a truck for 70 km. Mandlazi died from his injuries (Mhlabane, ).

Similarly, there has been ongoing violence perpetrated by the state against those in police custody and those protesting against poor government service delivery and low wages. The most high profile of these is the Marikana massacre in which 34 people were killed and 78 injured during a protest demanding better wages at the Marikana mine. Also, between 1997 and 2004, the Independent Complaints Directorate recorded 4,688 deaths in police custody showing ongoing abuses of police and state power (Bruce, ). This kind of violence has both similarities and differences to what is often (too loosely) referred to in South Africa as the legacy of violence that reflects new forms of social inclusion and exclusion even whilst the nature of the violence (including public necklacing and police violence against civilians) remains all too familiar.

Beyond the violence that is a familiar feature of South Africas racist past, political change has also been accompanied by new conflicts. One of the most notable has been violence against foreigners. This violence, made known to the world through the 2008 attacks on foreigners, has both familiar and unique qualities in a society for which violence has been a defining characteristic. The attacks began in Alexandra township north of Johannesburg and spread across the country (see Landau, for more). This violence has brought to the fore how notions of belonging and entitlement have been reshaped in post-apartheid South Africa as well as the limits to the tolerance and peace that is emblematic of the South African political transition.

Alongside the high levels of violence, South Africa has become well known for high rates of HIV infection. Indeed, the struggle against HIV began with democracy and has been one of the greatest challenges, testing political and democratic structures, family livelihoods and gender relations. Much has been written on how those infected with HIV are exposed to an ailing health-care system, social exclusion, discrimination and indignity (see, e.g. Le Marcis, ). That townships are more affected than suburbs and, within townships, informal settlements have the highest HIV infection rate shows the ways in which the disease mirrors other forms of social exclusion, marginalisation and inequality.

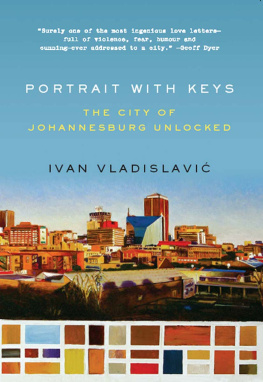

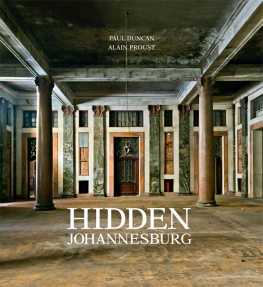

Johannesburg: The City from Above

Within this context of hope, transformation, marginalisation and violence, Johannesburg occupies an important material and symbolic space. In many ways it mirrors the image of South Africa painted above as a place of violence, disease, poverty and immorality. However, to many in South Africa, and beyond, it is also a place of opportunity and life change. Gauteng, the province in which Johannesburg is based, contributes 10 % of the GDP of the African continent and 33 % of the GDP of South Africa. It is a place of upward mobility and offers an opportunity to escape poverty and unemployment. However, it is also one of the most unequal places on earth with a Gini coefficient of 0.63. This means that peoples hopes for wealth are often difficult to attain. A city of migrants, 41.9 % of Gautengs population were born in Gauteng with everyone else having moved from across the borders or from another part of South Africa. Mahati () notes how children migrating to South Africa from Zimbabwe refer to the entire country as Jozia colloquial term for Johannesburgnot realising that South Africa is more than Johannesburg. In IsiZulu Johannesburg is known as Egoli or the place of gold. This refers to its mining history but also embodies the aspirations of many who have come to it since it was founded.

A place of myth and fantasy, sparked by the possibility of a new life, Johannesburg is also seen as exceptional and, more specifically, different from other African cities. This was perhaps most clear in a recent political gaffe by President Jacob Zuma when, in urging South Africans to pay tolls on Johannesburg highways, he said, We cant think like Africans in Africa generally. We are in Johannesburg. This is Johannesburg. It is not some national road in Malawi (Africa Check, ). Johannesburg is special.

In spite of the economic opportunities and sense of optimism that Johannesburg inspires, it is also a place of transience and social disconnection. Most people do not see Johannesburg as home and most would prefer to live elsewhere. And so peoples connection to the city is ambivalent. Whilst Johannesburg is a place of diversity with people from all over the continent, every linguistic and ethnic group and all religious affiliations, it is a place that people do not completely become a part of even if they lay claim to an entitlement to the city.