P ROLOGUE

T HE L AST R ACE OF THE C HAMPION

Weihsien, Shandong Province,China

1944

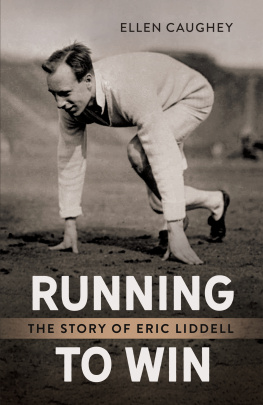

H E IS CROUCHING on the start line, which has been scratched out with a stick across the parched earth. His upper body is thrust slightly forward and his arms are bent at the elbow. His left leg is planted ahead of the right, the heels of both feet raised slightly in preparation for a springy launch.

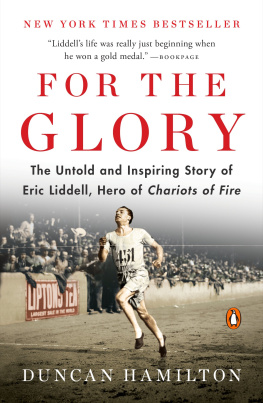

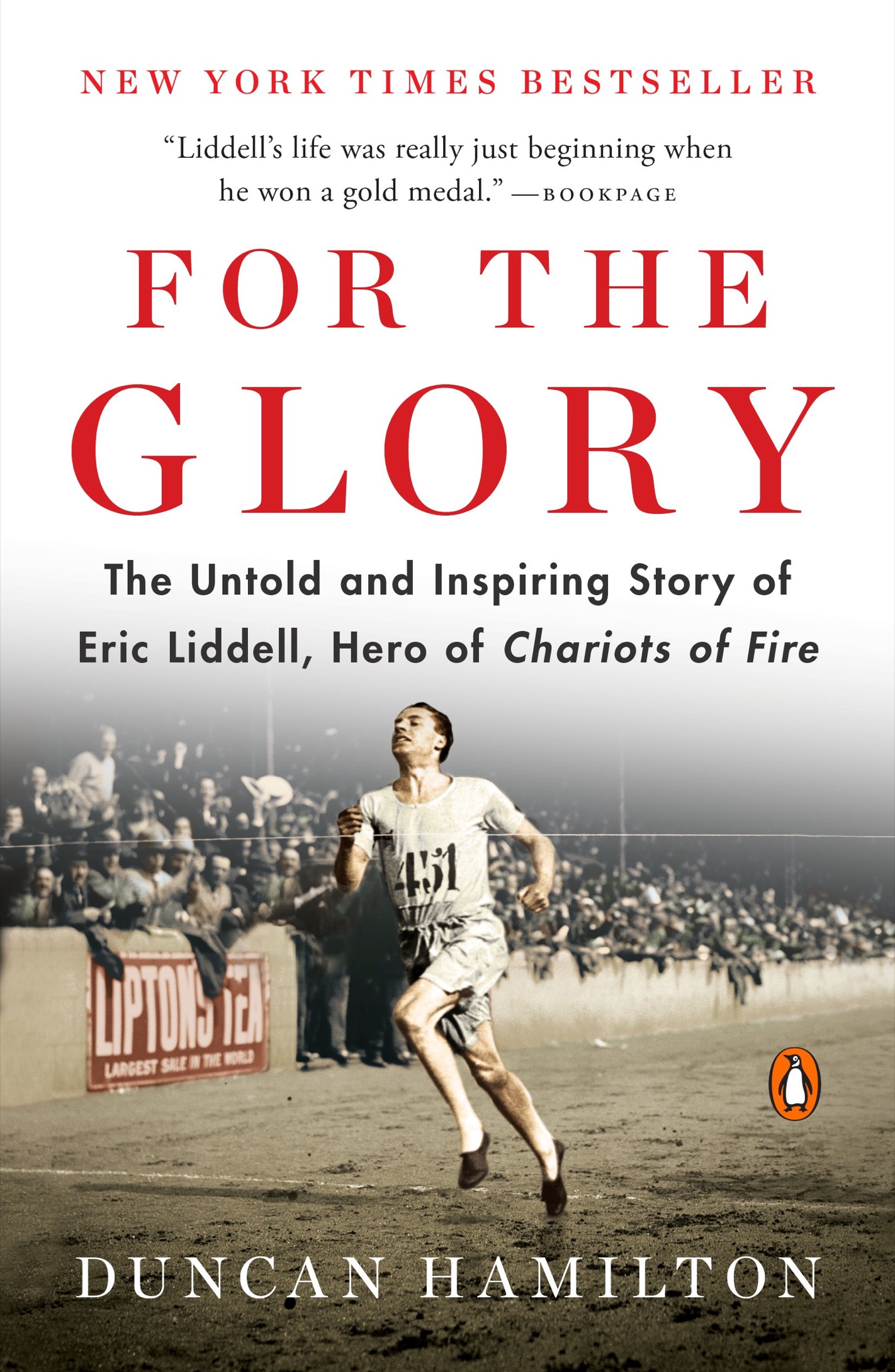

Exactly two decades earlier, he had won his Olympic title in the hot, shallow bowl of Pariss Colombes Stadium. Afterward, the crowd in the yellow-painted grandstands gave him the longest and loudest ovation of those Games. What inspired them was not only his roaring performance, but also the element of sacrificial romance wound into his personal story, which unfolded in front of them like the plot of some thunderous novel.

Now, trapped in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, the internees have teemed out of the low dormitories and the camps bell tower to line the route of the makeshift course to see Eric Liddell again. Even the guards in the watchtowers peer down eagerly at the scene.

In Paris, Liddell ran on a track of crimson cinder. In Weihsien, he will compete along dusty pathways, which the prisoners have named to remind them nostalgically of faraway home: Main Street, Sunset Boulevard, Tin Pan Alley.

Liddell claimed his gold medal in a snow-white singlet, his countrys flag across his chest. Here he wears a shirt cut from patterned kitchen curtains, baggy khaki shorts, which are grubby and drop to the knee, and a pair of gray canvas spikes, almost identical to those hed used during the Olympics.

As surreal as it seems, Sports Days such as this one are an established feature of the camp. For the internees, it is a way of forgettingfor a few hours at leastthe reality of incarceration; a prisoner wistfully calls each of them a speck of glitter amid the dull monotony.

Even though he is over forty years old, practically bald, and pitifully thin, Liddell is the marquee attraction. Those who dont run want to watch him. Those who do want to beat him.

Though spread over sixty thousand square miles, the coastal province of Shandong, tucked into the eastern edge of Chinas north plain, looks minuscule on maps of that immense country. Weihsien is barely a pencil dot within Shandong. And the camp itself is merely a speck within thata roll of land of approximately three acres, roughly the size of two football pitches. Caught in both the vastness of China and also the grim mechanism of the Second World War, which seems without respite let alone end, the internees had begun to think of themselves as forsaken.

Until the Red Cross at last got food parcels to them in July, there were those who feared the slow, slow death of starvation. Weight fell off everyone. Some lost 15 pounds or more, including Liddell. He dropped from 160 pounds to around 130. Others, noticeably corpulent on entering Weihsien, shed over 80 pounds and looked like lost souls in worn clothes. Morale sagged, a black depression ringing the camp as high as its walls.

Those parcels meant life.

While hunger stalked the camp, no one had the fuel or the inclination to run. So this race is a celebration, allowing the internees to express their relief at finally being fed.

Liddell shouldnt be running in it.

Ever since late springcumearly summer hes felt weary and strangely disconnected. His walk has slowed. His speech has slowed too. Hes begun to do things ponderously and is sleeping only fitfully, the tiredness burrowing into his bones. He is stoop-shouldered. Mild dizzy spells cloud some of his days. Sometimes his vision is blurred. Though desperately sick, he casually dismisses his symptoms as nothing to worry about, blaming them on overwork.

Throughout the eighteen months hes already spent in Weihsien, Liddell has been a reassuring presence, always representing hope. He has toiled as if attempting to prove that perpetual motion is actually possible. He rises before dawn and labors until curfew at ten p.m. Liddell is always doing something; and always doing it for others rather than for himself. He scrabbles for coal, which he carries in metal pails. He chops wood and totes bulky flour sacks. He cooks in the kitchens. He cleans and sweeps. He repairs whatever needs fixing. He teaches science to the children and teenagers of the camp and coaches them in sports too. He counsels and consoles the adults, who bring him their worries. Every Sunday he preaches in the church. Even when he works the hardest, Liddell still apologizes for not working hard enough.

The internees are so accustomed to his industriousness that no one pays much attention to it anymore; familiarity has allowed the camp to take both it and him a little for granted.

Since Liddell first became public propertyalways walking in the arc light of famewherever he went and whatever he did or had once done was brightly illuminated. The son of Scots missionaries who was born, shortly after the twentieth century began, in the port of Tientsin. The sprinter whose locomotive speed inspired newspapers to call him The Flying Scotsman. The devout Christian who preached in congregational churches and meeting halls about scripture, temperance, morality, and Sunday observance. The Olympic champion who abandoned the track for the sake of his religious calling in China. The husband who booked boat passages for his pregnant wife and two infant daughters to enable them to escape the torment he was enduring in Weihsien. The father who had never met his third child, born without him at her bedside. The friend and colleague, so humbly modest, who treated everyone equally.