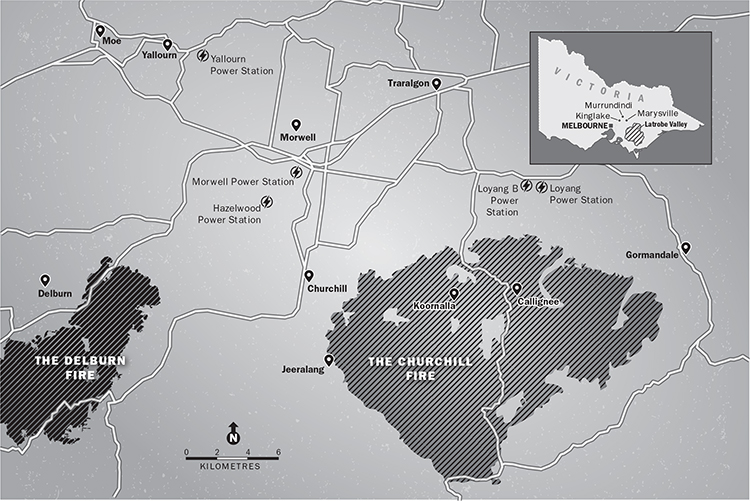

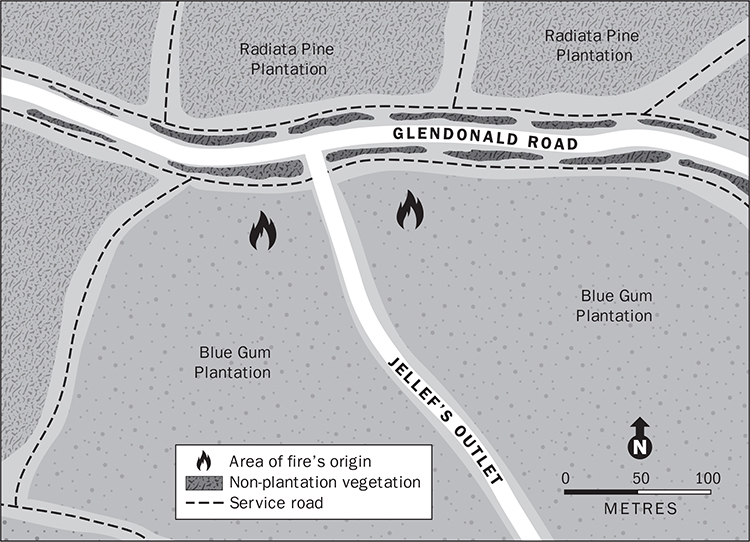

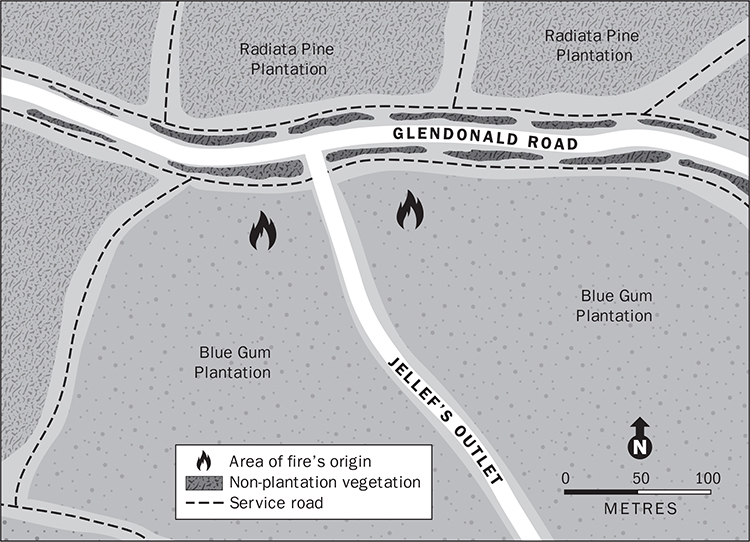

Map of the fires origins

Picture a fairytales engraving. Straight black trees stretching in perfect symmetry to their vanishing point, the ground covered in thick white snow. Woods are dangerous places in such stories, things are not as they seem. Here, too, in this timber plantation, menace lingers. The blackened trees smoulder. Smoke creeps around their charcoal trunks and charred leaves. The snow, stained pale grey, is ash. Place your foot unwisely and it might slip through and burn. These woods are cordoned off with crime scene tape and guarded by uniformed police officers.

At the intersection of two nondescript roads, Detective Sergeant Adam Henry sits in his car taking in a puzzle. On one side of Glendonald Road, the timber plantation is untouched: pristine Pinus radiata , all sown at the same time, growing in immaculate green lines. On the other side, near where the road forms a T with a track named Jellefs Outlet, stand rows of Eucalyptus globulus , the common blue gum cultivated the world over to make printer paper. All torched, as far as the eye can see. On Saturday 7 February 2009, around 1.30 pm, a fire started somewhere near here and now, late on Sunday afternoon, it is still burning several kilometres away.

Detective Henry has a new baby, his first, a week out of hospital. The night before, he had been called back from paternity leave for a 6 am meeting. Everyone in the Victoria Police Arson and Explosives Squad was called back. The past several days had been implausibly hot, with Saturday the endgame mid-forties Celsius, culminating in a killer hundred-kmh northerly wind. That afternoon and throughout the night, firestorms ravaged areas to the states north, north-west, north-east, south-east and south-west. Henry was sent two hours east of Melbourne to supervise the investigation of this fire that started four kilometres from the town of Churchill (pop. 4000). An investigation named, for obvious reasons, Operation Winston.

Through the smoke, and in the added haze of the sleep-deprived, he drove with a colleague along the M1 to the Latrobe Valley. On the radio, the death toll was rising fifty people, then a hundred. Whole towns, it was reported, had burned to the ground. The officers hit the first roadblock an hour out of the city. The dense forest of the Bunyip State Park was on fire, and the traffic police ushered them past onto a ghost freeway. For the next hour they might have been the only car on the usually manic road.

Outside, a string of towns nestled in the rolling green farms of Gippsland, and then it changed to coal country. Latticed electricity pylons multiplied closer to their source, their wires forming waves over the hills.

Turning a corner beyond Moe, Henry saw the cooling towers and cumulus vapours of the first power station, then, round the next bend, a valley ruled by the eight colossal chimneystacks of another station called Hazelwood. A vast open-cut coalmine abutted the highway. Layers of sloping roads descended deep into a brown core the carbon remnants of a 30-million-year-old swamp where dredgers, shrunk by a trick of the eye to Matchbox versions, relentlessly gouged the earth.

He turned off to Churchill, a few kilometres south of the highway. The town, built in the late 1960s as a dormitory suburb for electricity workers, had wide streets and a slender, anodised statue rising thirty metres out of the ground. It was the sole public monument, commemorating the great man of Empire in the form of a stylised golden cigar.

The detective didnt stop. He could see smoke above the blackened hills circling the town and wanted to get to the fires suspected area of origin before it was disturbed. If this was a case of arson, the police needed to prove the connection between the point of ignition and the victims, some of whom were likely to be kilometres away in places still too dangerous to access.

Passing the final roadblock, Henry parked and sat looking at the Nordic dreamscape on one side of the road, and the blackness on the other the axis where the world had tilted.

Out of the car, it was eerily quiet. No birds cried, no insects thrummed their white noise. The air was cool, pungent with eucalyptus smoke. A not unpleasant smell. On the other side of the police tape, Henry saw the police arson chemist.

George Xydias had slightly hunched shoulders and a slant to his neck as if from his many years looking for clues in ashes and rubble. He had investigated accidental fires and deliberate fires; explosions in cars, boats, trucks, planes; and, after the terrorist attacks of 2002, nightclubs in Bali. He had been to so many scorched crime scenes he could smell what type of vegetation or building material had just been incinerated, and even to the irritation of those in his laboratory, exposed by his meticulous ways the percentage of evaporated fuel sometimes left behind.

Wearing disposable white suits, Xydias and his assistant were talking with Ross Pridgeon, a bespectacled, shy, dryly humorous man with a mop of shaggy brown hair. Pridgeon, a local wildfire investigator from the Department of Sustainability and Environment, had been the first to examine the scene that morning. Amongst the precise rows of smouldering blue gums, hed found signs of two deliberately lit fires, a hundred metres apart on either side of Jellefs Outlet.

Pridgeon showed the assembled police team how hed traced his way to the place where the two fires joined. Three hundred metres along the outlet, flames had crossed from the east side to the west, high up, flashing in the tops of the trees. This was where a head fire one of the two burgeoning fire fronts had come surging through. The eucalypt crowns had been stripped out and the remaining blackened leaves appeared stiff, snap-dried, arrowing in the direction of Saturdays wind. The gum leaves, pliable up to a certain temperature, were like thousands of fingers pointing the way the fire had gone: a sign to the investigators that if they entered the fire zone here and moved back in the opposite direction, they might come to where it started.