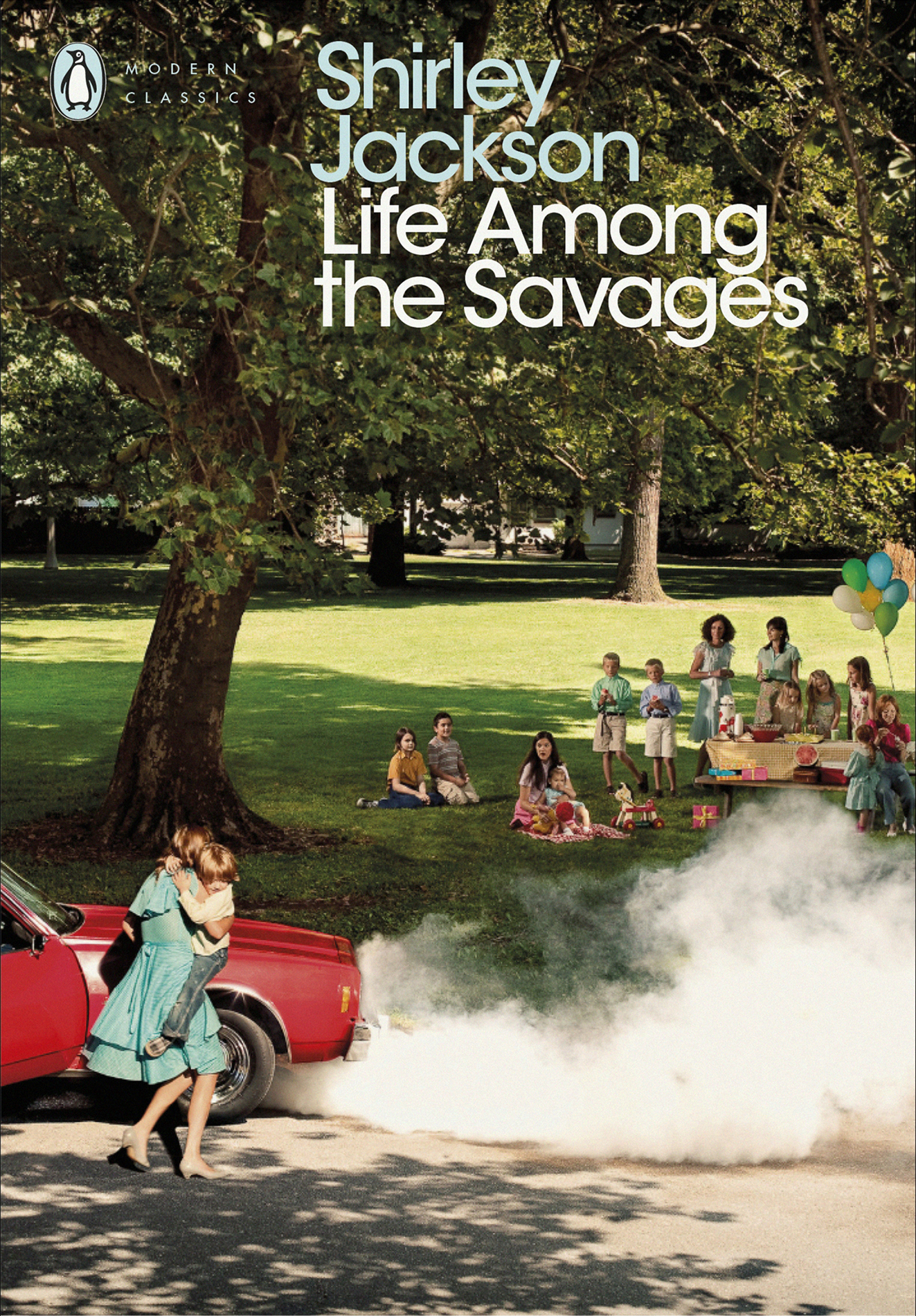

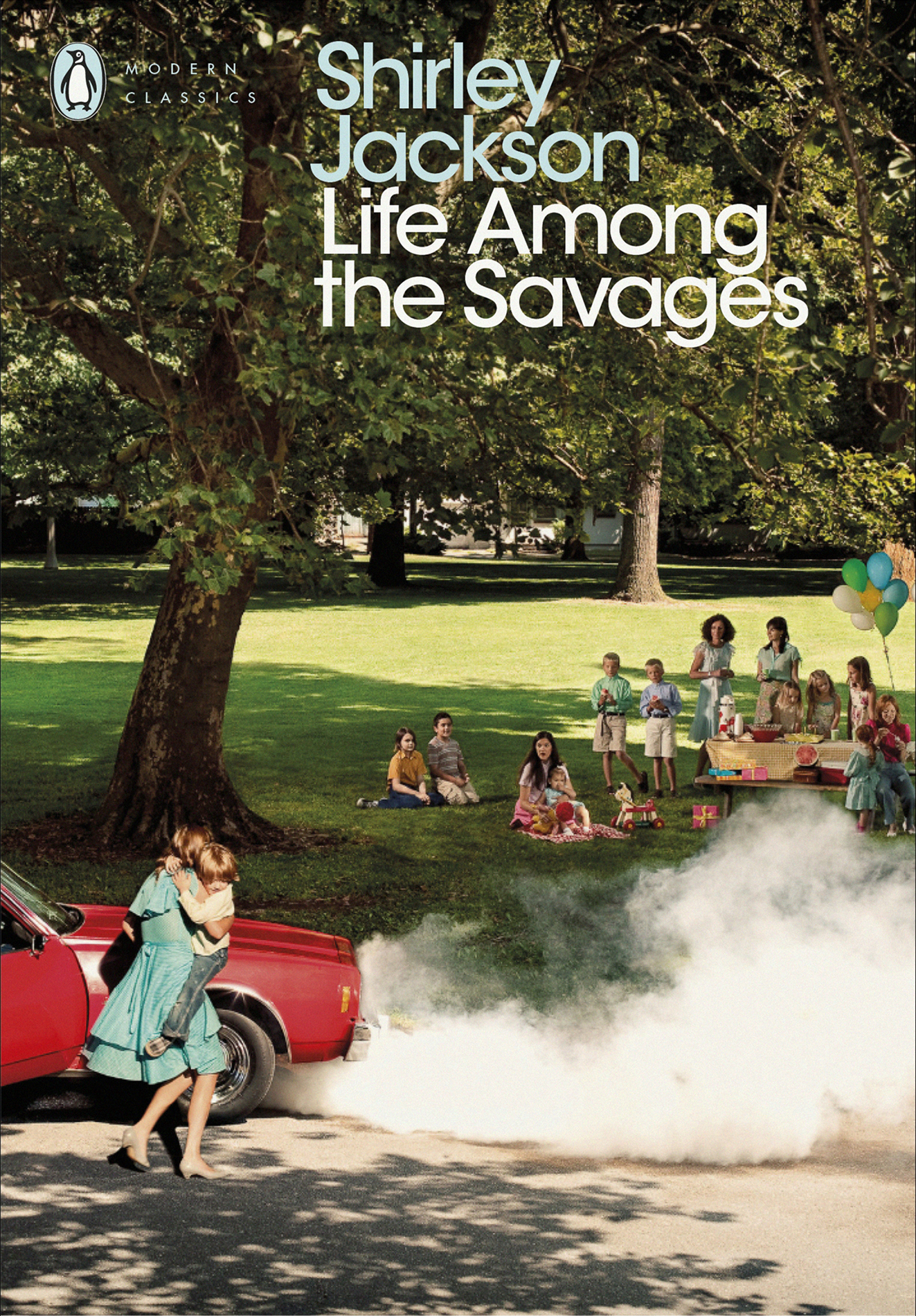

Shirley Jackson

Life Among the Savages

Contents

About the Author

Shirley Jackson was born in California in 1916. When her short story The Lottery was first published in the New Yorker in 1948, readers were so horrified they sent her hate mail; it has since become one of the most iconic American stories of all time. Her first novel, The Road Through the Wall, was published in the same year and was followed by Hangsaman, The Birds Nest, The Sundial, The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, widely seen as her masterpiece. In addition to her dark, brilliant novels, she wrote lightly fictionalized magazine pieces about family life with her four children and her husband, the critic Stanley Edgar Hyman. Shirley Jackson died in 1965.

Also by Shirley Jackson in Penguin Modern Classics

The Lottery and Other Stories

The Road Through the Wall

Hangsaman

The Birds Nest

The Sundial

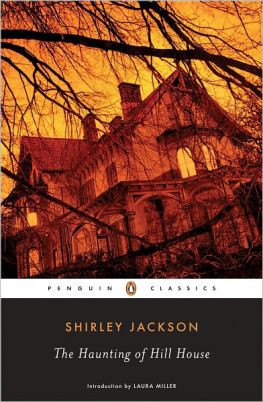

The Haunting of Hill House

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

Just an Ordinary Day

Let Me Tell You

Dark Tales

For the Childrens Grandparents

One

Our house is old, and noisy, and full. When we moved into it we had two children and about five thousand books; I expect that when we finally overflow and move out again we will have perhaps twenty children and easily half a million books; we also own assorted beds and tables and chairs and rocking horses and lamps and doll dresses and ship models and paint brushes and literally thousands of socks. This is the way of life my husband and I have fallen into, inadvertently, as though we had fallen into a well and decided that since there was no way out we might as well stay there and set up a chair and a desk and a light of some kind; even though this is our way of life, and the only one we know, it is occasionally bewildering, and perhaps even inexplicable to the sort of person who does not have that swift, accurate conviction that he is going to step on a broken celluloid doll in the dark. I cannot think of a preferable way of life, except one without children and without books, going on soundlessly in an apartment hotel where they do the cleaning for you and send up your meals and all you have to do is lie on a couch andas I say, I cannot think of a preferable way of life, but then I have had to make a good many compromises, all told.

I look around sometimes at the paraphernalia of our livingsandwich bags, typewriters, little wheels off thingsand marvel at the complexities of civilization with which we surround ourselves; would we be pleased, I wonder, at a wholesale elimination of these things, so that we were reduced only to necessities (coffeepot, typewriters, the essential little wheels off things) and thenthis happening usually in the springtimeI begin throwing things away, and it turns out that although we can live agreeably without the little wheels off things, new little wheels turn up almost immediately. This is, I suspect, progress. They can make new little wheels, if not faster than they can fall off things, at least faster than I can throw them away.

I remember the morning, long ago, when the landlord called. Our son Laurie was three and a half, and our daughter Jannie was six months old, and I had the lunch almost ready and the diapers washed, along with the little shirts and the nightgowns and the soakers and the cotton blankets, and they were all drying on the line (and I dont care what anyone says, thats a mornings work, when you consider that I had also made brownies and emptied the ashtrays) and then the landlord called. He was a kindly man, and a paternal one, so that he asked first about my health, and my husbands health, and then he asked how was our boy? and how was the baby? and when I said that we were all fine, fine, he said that of course we were aware that our lease was up? I said well, no, we hadnt really known that our lease was up. So he said well, he supposed that we hadnt looked at the lease recently and I (wondering if that was the paper Laurie had torn up and eaten) said that it had been quite a while, really, since we sat down together and read over our lease. That was too bad, he said. Wasnt it, I said. Because, he said, his voice gentle, the apartment had been rented to someone else. After a minute I said rented? to someone else? Then I laughed and said what were we supposed to domove? He said well, yes, we were supposed to do just that.

Naturally, he went on, we could evict you if we wanted to.

You could? I was thinking of letters to the president, appeals for the sake of our two small children. Wed much rather youd just move out, he said.

But where?

He laughed genially. Ask me another, he said. Apartments are mighty tough to find these days.

I suppose we could take a look around, I said dubiously. Letters, I was thinking, sue them for the piece of plaster that fell on my husband while he was shaving: lawyers.

Well expect to take possession around May first, he said.

Today is March twenty-fifth, I said.

Thats right, he said. Rent almost due, and he laughed again.

The next day we got a letter saying that it was first notice of warning to evict. I began to think in terms of pouring boiling oil from the windows and barricading the doors with the dining room table. What made both of us even angrier was the fact that we had never had any intention of renewing our lease, but had planned vaguely on moving as soon as we found another place. The very idea, I told my husband indignantly, renting this apartment to someone else without fixing that broken step. The one on the stairs.

Leave a note for the new people about the cockroaches, my husband advised. He also advised strenuously against bringing suit for some undetermined reason (the piece of plaster? the neighbors radio?) and said, patting me on the shoulder, that he knew how anxious I had been to find another place.

Our fondest dream had been to move to Vermont, to a town where a couple we knew had settled and from which they had written us glowing accounts of mountains, and children playing in their own gardens, and clean snow, and homegrown carrots, and now suddenly it looked overwhelmingly as though we moved either to Vermont or to a tent in the park. I called half a dozen city agents, and they all laughed as gaily as our landlord had laughed; Got any relatives you could move in with? one of them asked me.

Finally, two hardy adventurers making for unexplored territory, we left the children with their grandparents, got ourselves and our suitcases and our overshoes onto a train at the station, and set out, an advance scouting party, for the small town where our friends lived, and where the mountains were so high and the snow so clean. There was no doubt, we discovered, about the snow. Our city overshoes went in over their heads as we stepped off the train, and for the three days we were there we both went constantly with damp feet and small bits of ice melting against our socks.

Next page