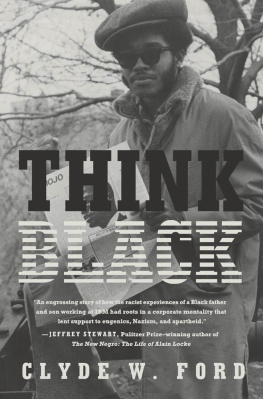

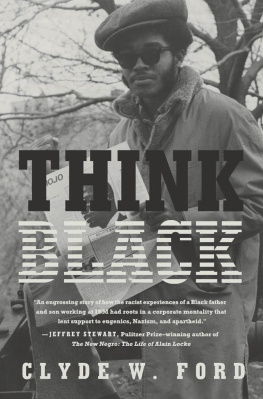

The authors father in the mid-1950s with his IBM colleagues.

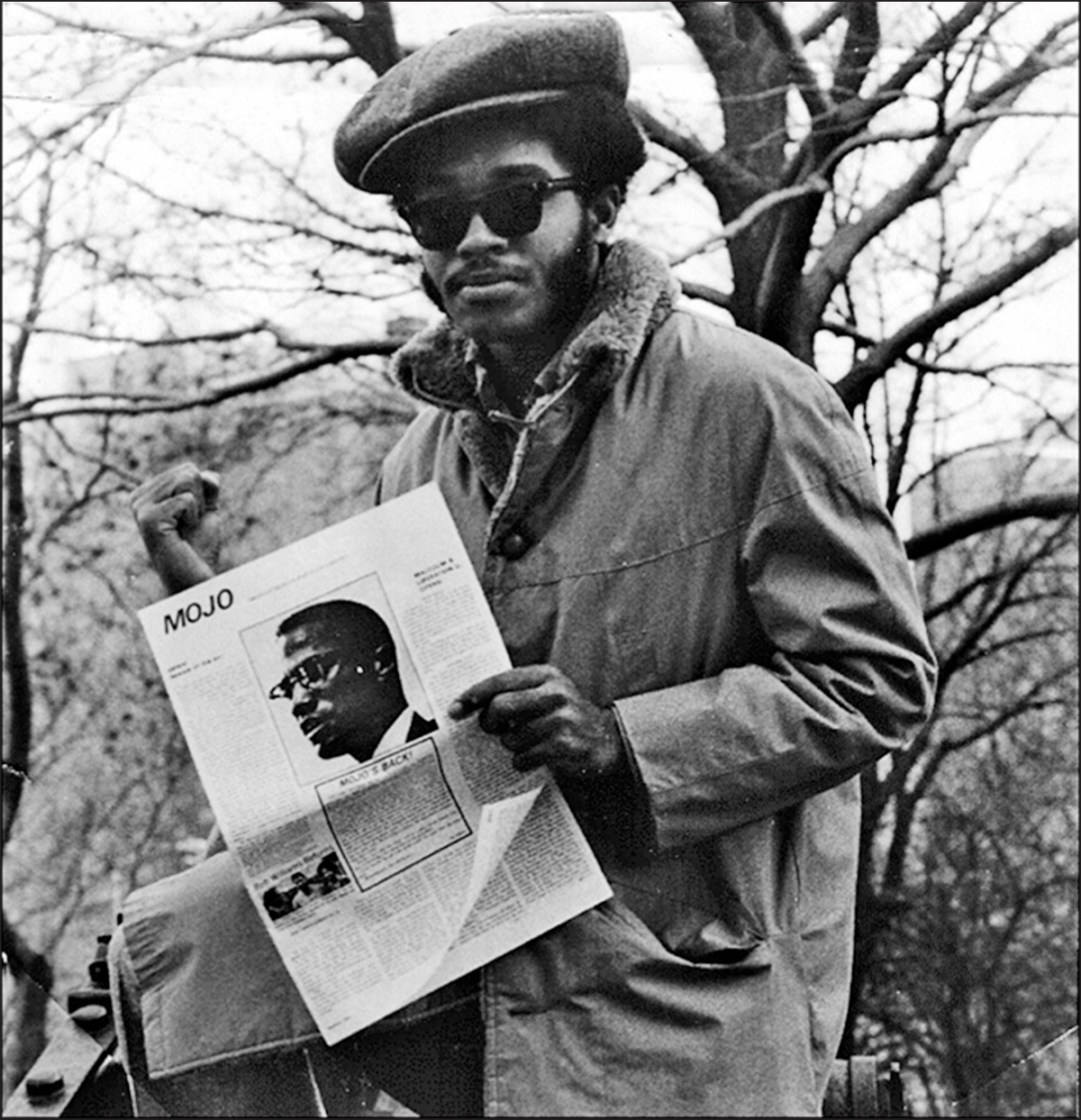

I held fast to an overhead bar as the elevated train I rode in swayed side to side, rocketing into Manhattan from the Bronx. When it dove beneath the Harlem River, everything outside the car went dark, and I caught a reflection of myself in the window: a ballooned Afro, pork chop sideburns, a blue zoot suit with red pinstripes, a fire engine red turtleneck, a trench coat with its collar turned up.

A half hour later, I strutted from the subway through the light rain hanging over Wall Street, humming the theme song to the film Shaft, which Id seen the night before. I fancied myself as the movies Black hero, about to engage in battle with the White troops of injustice arrayed before me. I entered one of the skyscrapers squeezed into the Financial District and took an elevator to a higher floor. There, stenciled in blue, the sign on the glass doors read IBM , and beneath it in white: NEW YORK FINANCIAL OFFICE . I grasped the door handle but paused, catching another glimpse of myself in the glass door pane. I shook my head, unsure of what to make of this decision, unready to push through those glass doors, uncertain of what fate awaited me on the other side of the threshold.

On that fall day in 1971, I was young and Black, defiant and angry, and more than ever determined not to be like my father. Yet there I stood, about to report for work at IBM, where hed worked for twenty-five years.

When I finally pushed through the double doors, conversation stopped. The whiz-peck-whiz of Selectric typewriters fell silent. Many heads turned toward the teenager with the huge Afro, who now stood inside their doors. For an instant, I held hostage some fifty men in white shirts and ties, cradling telephone headsets, and a dozen female secretaries with their fingers perched on typewriter keys. I scanned the room for Black faces, but found only three: two men immersed in a sea of White faces at the center, and a young woman at work as a secretary to my left.

Art Conrad, the branch manager, stood abruptly when I entered his office. He embodied what I came to call the IBM managers looka man who could have played football in college, tall, broad-shouldered, square-jawed, solidly built, and White. He reached down to shake my hand.

IBM dress code, he said.

I didnt reply.

Conrad trained an intense stare on me. But I held my silent ground and returned his stare. At last, he seemed to finally relent.

Im supposed to give you this.

He handed me a small, open box containing a silver pen and pencil set nestled in cotton.

Thanks. I headed toward the door.

Ford.

I spun back around.

Take any empty seat. He pointed toward the open floor. You wont be here long.

Excuse me?

His devilish grin now seemed to be payback for my previous silence. Class, he said. Youll be in class for the better part of a year.

I can only imagine his first entries in my employee file.

I took a seat partially hidden by one of the large pillars that supported the floor above. I had not been seated long when my telephone rang.

I like the way you look, the female voice said. She hung up.

I swung around to the secretarial pool, but no one looked back.

Soon after, a Black man casually made his way to my desk. He sat on the edge and leaned over.

Names Harold, he said. Harold Brown.

Clyde Ford.

Listen, Clyde. You want to do well in this company? Take some advice. Suit? Lose it! Get a plain suit, dark blue or gray. Normal length. No wide lapels. Wear a white shirt, maybe light blue shirt. Red or blue tie. You want to be different? Try a three-piece suit, a button-down shirt, or a dotted tie.

Harold pulled up a pant leg. Dark socks. Black or dark brown shoes.

He looked at my Afro and pork chop sideburns, ran a hand through his crew cut, and smoothed the sides of his face. Man, I dont know what to tell you about all of that hair. Its embarrassing. You just dont get it, do you? Youre working for IBM now.

Harold made his way back to his desk, shaking his head.

In fact, it was Harold who didnt get it. I may have been nineteen years old, still a teenager, that first day at work, but nothing about my dress or my demeanor was unconscious or unintentional.

* * *

A generation earlier, in 1947, my father also gazed across a similar threshold, into an IBM office in New York City. He was a member of the Greatest Generation and had been a first lieutenant in the famed Black 369th Infantry Regiment of the US Army. From the photographs I saw of my father as a young man, at twenty-seven years old he cut a handsome figure in his dark gray suit, red striped tie, and wide-brimmed hat with a satin band. But instead of defiance, he masked diffidence; instead of anger, he displayed anticipation; instead of determination not to be like his father, he stood ready to prove to everyone, including his father, that he deserved to be the first Black systems engineer to work for IBM.

It was the late 1940s, postWorld War II America. Anything was possible! Duke Ellington swung jazz. Jackie Robinson swung a big-league bat. Brown v. Board of Education swung through the courts. Nowhere were new possibilities and promises felt more deeply than in Harlem, which was then Black Americas gravitational center. In a City College classroom on the edge of Harlem, an accounting professor invited one of her students to dinner. The Black GI arrived at her swanky apartment dressed to the nines, and Thomas J. Watson Sr., founder of IBM, stepped from the shadows. Watson offered my father a job, and a Branch RickeyJackie Robinson moment ensued: the start of an unknown chapter in the history of modern-day computers.

As a staunch Dodgers fan, thoughts of Jackie Robinson could not have been far from my fathers mind as he crossed the threshold into IBM. Less than two years before, on October 23, 1945, Wesley Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to the Montreal Royals, a farm team of the Brooklyn Dodgers, thereby breaking the color line in Major League Baseball and ending decades of segregation. In the postwar Black community of New York City, as around the world, Jackie Robinson came to symbolize change and a long-fought, long-sought victory for racial justice. Though Robinson would wait until the spring of 1947 for his at-bat debut as a Dodger, by the time my father entered IBM in early 1947, Jackie Robinson had already taken firstnot first base but the status as the first Black ballplayer in Major League Baseball. And in this important regard, my father and Robinson played for the same team.

My father was not the first Black man hired by IBM. That distinction belonged to T. J. Laster, hired less than a year earlier. But Laster was hired as a salesman, making my father the first Black man hired to work as a systems engineer. And just like Robinson, hired by Branch Rickey, the head of the Dodgers organization, my father was hired by Thomas J. Watson Sr., the legendary president and founder of IBM.

From the military to academia, politics, the media, and entertainment, postwar America was a time of firsts for Black men and women. Many had risked their lives on the battlefields of Europe, Asia, and Africa. They had experienced a world where bravery, not skin color, determined their fate. Then they returned to America, to hatred, to Jim Crow, and to lynchings. Something had to give. A similar push for change after World War I stalled in the wake of mounting violence by White mobs. But this time, after World War II, a few Black men and women pushed, or were catapulted, past Americas discrimination.