Contents

Guide

In Memory of

Vincent Gordon Harding (19312014)

Lerone Bennett, Jr. (19282018)

Contents

Phillip Corvens case against Charles Lucas came before the Virginia Supreme Court on the afternoon of June 16, 1675, for final disposition, Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Chicheley presiding. Opposing counsels may have argued the case a few days earlier, on June 12, to the full court of Governor Sir William Berkeley. Most cases landed at the Virginia General Council (the colonial-era supreme court) on appeal. Either the petitioner, Corven, or the defendant, Lucas, presumably contested an adverse ruling by the lower Warwick County Court, which is how the case came up for final review by judges Henry Chicheley (knighted by Charles I), Thomas Bacon, James Bridger, Phillip Ludwell, James Bray, and William Cole.

We know for certain that Phillip Corven was a Black man, his case officially annotated as the Petition of a negro for redress, etc. In his initial filing, Corven presented details of how he had been treated like property: Anne Beasley bequeathed him to her cousin, Humphrey Stafford, who then sold him to Charles Lucas.

Phillip Corven, however, asserted he was not a slave. Beasleys will stipulated an eight-year indenture, after which Corven was to have been given his freedom. But Lucas, his present master, had forced Corven to work three years longer than the terms of that will. Then, after those eleven years of service, Lucas forced Corven to sign an indenture for an additional twenty years, under threats & a high hand, Corven said.

At that point, Phillip Corven had had enough. He took his case to the judicial system of colonial Virginia, demanding not only his freedom but also the three barrels of corn and a suit of clothes promised him in Anne Beasleys will; that promise was widely known in colonial America as freedom dues.

Chicheley handed down the supreme courts ruling, from which there would be no subsequent appeal: Petitioners twenty-year indenture? Vacated. Petitioners request for freedom? Granted. Petitioners request for court costs paid by defendant Lucas? Granted. Petitioners request for freedom dues from defendant? Granted.

Freedom dues is an idea as old as America. Not expressed in the Declaration of Independence, nor enshrined in the Constitution, nor enumerated in the Bill of Rights, freedom dues, nonetheless, arrived on Americas shores with the first colonists: a belief that power and wealth created from the labor of others entitled those who helped create that power and wealth to their fair share.

Stolen from Africa, hoodwinked, captured, or voluntarily signed on from Europe, in the early 1600s, indentured servants worked in the fields of colonial planter-masters without pay. But unlike slaves, bound in perpetuity, the labor of indentured servants had limits. They entered into contracts with their masters, offering their service for four, five, seven, eleven, fourteen years, and in some cases longer.

At the end of their bondage, indentured servants expected not only their freedom but also their freedom duessome combination of land, seed, tools, and clothes to help them begin anew. Freedom dues represented a promise: for a very few, a path up from poverty into the wealth, security, and prominence of the privileged planter class; for most, at least the bare essentials of subsistence living, enough to keep poverty at bay.

This book focuses on the clash and convergence of two fundamental human conditionsfreedom and bondageand how that clash and convergence has played out in America.

The clash between freedom and bondage is obvious.

Not surprisingly, many masters, like Charles Lucas, refused to pay freedom dues, especially when it came to land grants. This failure to pay freedom dues was but one of many means by which landholding masters thwarted the aspirations of indentured servantsbrutal working conditions, refusing to abide by contracts, arbitrary extension of the terms of indenture were others.

But landowners fought most bitterly to prevent those formerly bonded to them, Black or White, from owning land, which, after all, was the basis of colonial-era power and wealth. So, in this conflict between those who owned land and those who felt deserving of land lies another, equally potent force coursing through early Americathe amassing of wealth and power by a few, and the denial of even a portion of that wealth and power to many.

Here is the earliest glimmer of the 1 percent in America, for the roots of wealth inequality lay in this gathering and holding tight of land. Here, too, lay the earliest roots of the 99 percent calling for a reversal of this inequality in the form of freedom dues. And this contest between masters and servants; between the landed and the landless; between those denying freedom dues and those demanding them; between freedom and bondage, has animated America ever since.

The convergence between freedom and bondage is less obvious.

In his books and lectures, the late Edmund S. Morgan, a professor of American history at Yale University, captured this convergence succinctly. In America, Morgan said, freedom presupposes bondage; in other words, there is no freedom without bondage. Heres what Morgan was getting at. Take any of the slaveholding Founders, for example: Washington, Jefferson, or Madison. In previous generations, they were considered heroes because of the lofty ideals of freedom and equality they espoused. The fact that they owned slaves was never an issue, even though slavery was diametrically opposed to freedom. In modern times, the fact that most Founders owned slaves looms large; for some, this hypocrisy looms larger than the ideals of freedom they espoused. On one hand, freedom is most important. On the other hand, bondage is most important. Morgan would say that either position misses a deeper truth, a truth that is both more revealing and more damning.

Without slavery, the Founders would not have been able to pontificate on the lofty ideals of freedom that made their way into documents like the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. They would have been so tied to their land, growing their crops, mostly tobacco, that they simply would not have had time for anything else. Cultivating tobacco, it turns out, even with slave labor, was incredibly time-consuming. Thus, freedom in early America was a privilege that derived from slavery.

This idea of an inextricable link between freedom and slavery proves to be extremely useful. Its a means for understanding why almost 25 percent of the US Constitution is related to the support of slavery, while the word slavery is never mentioned in the original text. Its a tool for examining the Emancipation Proclamation, and Lincolns motives, then realizing the proclamation itself did not free a single slave. And, its the basis for understanding how Black labor built White power and wealth.

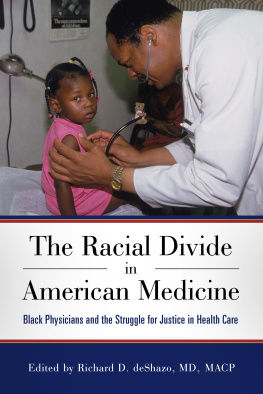

If, historically speaking, there was no freedom without slavery in America, then the institutions of power and wealth that emerged in America owe themselves to the slavery upon which America established its freedom. Pick an institution, any institutionagriculture, politics, jurisprudence, religion, medicine, policing, finance, transportation, militaryapply Morgans rule, and youll discover that as a means of power and wealth, that institution is rooted in slavery. In fact, thats exactly what this book intends to doexamine how American institutions of power and wealth came about as the result of Black labor, which before 1865 meant, for the most part, slavery.

Sometimes, the answer to the question of how Black labor built a particular institution of White power and wealth will be direct. Take agriculture. Black labor, slave labor, by working in farm fields, literally built the agricultural industry in America as one of the first institutions of power and wealth. At other times, the answer to this question will be indirect. Like policing. Black men and women had no direct hand in creating the institution of policing, an obvious instance of power used to protect White wealth. But the institution of policing was created to control the labor of Black men and women. Without the need of White slave owners to control their slave populations, policing may not have developed in America the way that it did. And occasionally, the answer will be both direct and indirect. How did Black labor build Wall Street? Turns out slaves actually built the wall, but slavery was also the basis for many of the financial instruments and investment vehicles used by brokers on the Street.