The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For my Mother

and for Catarina

We need to expand the civil-rights struggle to a higher levelto the level of human rights. Whenever you are in a civil-rights struggle, whether you know it or not, you are confining yourself to the jurisdiction of Uncle Sam. No one from the outside world can speak out in your behalf as long as your struggle is a civil-rights struggle.

Malcolm X, The Ballot or the Bullet

So Black Power is now a part of the nomenclature of the national community. To some it is abhorrent, to others dynamic; to some it is repugnant, to others exhilarating; to some it is destructive, to others it is useful. One must look beyond personal styles, verbal flourishes and the hysteria of the mass media to assess its values, its assets and liabilities honestly.

Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

PREFACE

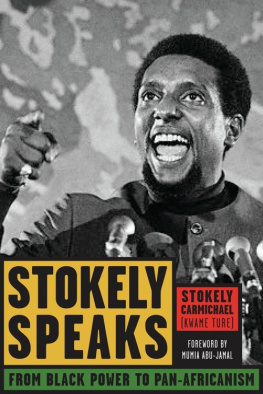

The Black Power movement remains an enigma. Historians trace its origins to Stokely Carmichaels defiant declaration during the June 1966 Meredith March, which would unleash a movement that would peak with the calls for armed struggle announced by the Black Panthers, and inspire the poetry and race consciousness of the Black Arts movement. In the popular mind, Black Power is most often remembered as a tragedya wrong turn from Martin Luther King Jr.s hopeful rhetoric toward the polemics of black nationalists who blamed whites for the worsening urban crisis, on the one hand, and, on the other, gun-toting Black Panthers who vowed to lead a political revolution with an army of the black underclass.

Waiting Til the Midnight Hour reconsiders this story, arguing that understanding the history behind the iconic Black Power imageryclenched fists, Black Panthers, racial upheavals, dashiki- and afro-wearing militantsrequires plumbing the murky depths of a movement that paralleled, and at times overlapped, the heroic civil rights era. Early Black Power activists were simultaneously inspired and repulsed by the civil rights struggles that served as a violent flashpoint for racial transformation. Occupying marginal arenas of black life that Ralph Ellison characterized as the lower frequencies, radicals laid the groundwork for the racial militancy, cultural transformation, and political organizing of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the time in which Black Power occupied the national stage.

Black Power at the local, national, and international level would launch a radical political movement that while racially specific was nevertheless interpreted by a variety of multiracial groups as a template for restructuring society. Black Power, beginning with its revision of black identity, transformed Americas racial, social, and political landscape. In a premulticultural age where race shaped hope, opportunity, and identity, Black Power provided new words, images, and politics. If the movements confrontational posture quickened the pace of racial change, it also provoked a visceral reaction in white Americans who could more easily identify with civil rights activists than with Black Power militants. Ultimately, Black Power accelerated Americas reckoning with its own uncomfortable, often ugly, racial past, and in the process spurred a debate over racial progress, citizenship, and democracy that would scandalize as much as it would change the nation.

INTRODUCTION

TO SHAPE A NEW WORLD

Malcolm X arrived in Harlem in the early 1950s on the heels of the contentious departure of another of its adopted, if little-known, sons. As Malcolm was bounding into Harlems local political arena, Harold Cruse was settling downtown, still clinging to wistful dreams that he had, temporarily at least, put on hold. As a young boy, Harold Cruse dreamed of becoming a writer. For a southern-born black boy coming of age in the Great Depression, this was an ambitious goal, with long odds. Born in Petersburg, Virginia, in 1916, Cruse moved as a young boy to New York City as part of the exodus to northern cities that would shortly transform African American life. The then-largest internal migration in American history sowed the seeds for Harlems emergence as a cultural mecca that would become the headquarters for black political resistance, intellectual achievement, and cultural innovation. A second great migration, which started during the early 1940s, of southern-born blacks (which eventually eclipsed its earlier counterpart in both density and geographical breadth), extended to cities and regions recently buoyed by the movement for civil rights. Coalitions of civil rights activists, trade unionists, Communists, and Pan-Africanists led strategic campaigns for racial justice and radical democracy that stretched from gritty Harlem neighborhoods through Detroits industrial shop floors to Dixies cradle, Birmingham, Alabama, and out west to Oaklands postwar boomtown.

Cruses favorite time was spent reading books at the local library. It was no ordinary public library. Harlem was home to the New York Public Librarys Negro History Division, a repository of black history and culture founded by the Afro-Puerto Rican bibliophile, historian, and curator Arturo Schomburg. Schomburgs passion for African, Caribbean, and African American history provided the residents of Harlems black community a window onto its past.

In the 1950s, black nationalists stalked Harlem like itinerant Baptist preachers in search of wayward flocks, wistful for the heady postWorld War I years, when New Negroes reshaped Afro-America with a dose of militancy as effervescent as it was unprecedented. Marcus Mosiah Garveys dynamic presence had fueled this golden age, when the Universal African Legions (soldiers in Garveys Universal Negro Improvement Association) held Harlem captive with precision marching, ornate uniforms, and defiantly proud stares. No sooner had Garvey overcome what appeared to be insurmountable organizational, financial, and political obstacles than his movement collapsed, victimized by internal ineptitude, government surveillance, and jealous rivals. Garveys arrest on charges of mail fraud, and subsequent incarceration during the mid-1920s, made room for other advocates of interracial class struggle who, during the height of the New Negro, could barely be heard above the din of nationalist fervor.

If Garveys absence created space for radicals, the Great Depression invited another front in the war for racial equality: class-based political agitation. With organizing energies fueled by social crises, the Communist Party (CP) made small, but surprisingly robust, headway in Harlem. While Garvey stoked controversy through grand gestures aimed at coaxing dignity from Africas descendants, the CP offered a Promethean vision of class struggle. As Cruse remembered, anyone who couldnt debate the finer points of Marx and Engels was considered a goddamned dummy!

By the late 1930s, the Depression introduced the possibilities of social, cultural, and political revolution at home and abroad and reached Harlems street corners, barbershops, churches, and other institutions. Much of Cruses early political education took place at the Harlem YMCA, which served as a debating society, intellectual training ground, and incubator for what Cruse later described as a hotbed of political activity. The all-black neighborhood blurred class distinctions among Afro-Americans, where Harlemites rubbed shoulders with leading black literary lights. Virtually every block of Harlem was up for grabs: nationalists exhorting on one corner, while Socialists and others set up their headquarters fifty yards away. Pamphlets on class struggle, Pan-Africanism, and trade unionism compressed decades of social history into easily digestible prose. Walking through parts of Harlem, you risked being bombarded by pamphleteers selling, or sometimes giving away, propaganda that recounted the history of Negro oppression and offered a blueprint for black liberation.