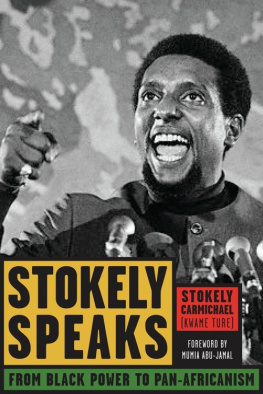

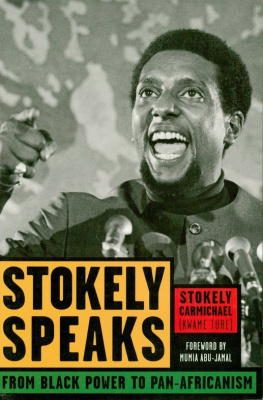

Cover photo: Stokely Carmichael speaking at a civil rights rally, 1970.

Copyright Bettmann/CORBIS

Cover design: Sommers Design

If We Must Die, by Claude McKay, is reprinted by permission of Twayne Publishers, Inc. from Selected Poems of Claude McKay.

Copyright 1953 by Bookman Associates, Inc.

This book is dedicated to President Ahmed Sekou Toure and Mme. Tour and to my brothers and sisters in Guinea who have suffered much to maintain Africas dignity and sustain Africas will to survive.

Foreword

I dont know what I expected when I received and read this text of letters, articles, and speeches by the late Kwame Ture (ne Stokely Carmichael).

The man wasnt a complete cipher.

During the period of my youthful membership in the Black Panther Party (Philadelphia chapter), this outspoken, fiery rebel held the rank of Honorary Prime Minister. When our West Philadelphia office held community political education (P.E.) classes, we often featured the Liberation Newsreel black and white film of the rally in the Bay Area for the freedom of Minister of Defense Huey P. Newton. There, standing tall, lean, and black as a Masai warrior, stood Stokely Carmichael, spitting fire and rage, lightly seasoned with his Trinidadian clip of the English tongue.

I had even met him, albeit briefly, in my life as a reporter, when I covered a speech he gave in the 1970s, in a run-down storefront in North Philadelphia. After the speech, he was gracious enough to grant a brief interview.

Yet, upon reading his own words, I was surprised. Indeed, I was surprised at how surprised I was.

For it dawned on me that, during my midteens, and even into my first fires of adulthood, I learned about Stokely by the words of others.

Press reports. Its amazing how those of us who consider ourselves revolutionaries still rely on the words of the white supremacist corporate pressa true enemy of the Black Liberation movement if ever there was one.

Or even in the Black revolutionary nationalist press, as, in my case, The Black Panther.

I was surprised, even though Id read (long ago), and recently reread, Black Power, the work penned by him and Charles V. Hamilton.

I often wondered, in a critical, small-minded way, How much of this was written by Stokely, and how much by Hamilton? And while Im sure I saw this book on shelves, on tables, and, yes, in recycling bins, I didnt buy it. I didnt read it. By then, the Party had declared him a cultural nationalist a term that, at the time, was tantamount to Enemy.

A good, loyal Party member didnt read such stuff. And, to my shame, I didnt.

I am blown away by his brilliance, his insights, his sharpness, his profound love of African people, and lastly, his humility.

In one of his last entries in this slim yet packed volume, Ture tells Black college students (at Morehouse and Federal City Colleges) that true revolutionaries must not bum-rush the mic but take the valuable time to study. He explains:

Because revolutionary theories are based on historical analysis, one must study. One must understand ones history and one must make the correct historical analysis. At the correct moment you make your historical leap and carry the struggle forward. Not only that, you cannot rap if you really dont believe what youre saying, or if you dont know the answers. Fourteen months ago it became clear to me that the black community was heading for political chaos. I knew that I didn,t have the answers, so it was silly for me to stay here and keep rapping about what I didnt know. Why should I stay here to get up on television and yell a lot of nonsense? It would only cause confusion in my community. I didnt want to do that. Confusion is the greatest enemy of revolution. (Italics added)

BoyI bet you didnt see those kinds of admissions often among leaders! And speaking of leaders, what would history have been if Ture did not leave the Party? What if the Party was big enough, strong enough, mature enough to include his insights into their own? Ture writes (in Pan-Africanism) of the ideological issues that separated him from the Party. Although he is not explicit, the issue was working with whiteradicals, something Ture found untenable. Ironically, the ideological positions between Huey P. Newton and Stokely Carmichael were perhaps closer than first thought. As early as 1971, Newton recognized that the Partys work with white radicals was unproductive, for White radicals did not give us access to the White community because they do not guide the White community. One cannot read Stokelys trenchant analysis of white liberalism without coming to the same conclusion (see his January 1969 speech, The Pitfalls of Liberalism). In the decades since this revolutionary era, we have seen how so-called radicals become liberals and, in current parlance, neoliberals (not to mention neoconservatives).

Moreover, one must be ever mindful of the efforts of the State to create, expand, and exploit divisions between Black revolutionaries. In perhaps the most infamous of the COINTELPRO documents yet uncovered, where the FBI announced as one of its primary objectives to prevent the rise of a [Black] messiah, Stokelys name was listed among them.

A steadfast Pan-African revolutionary, Ture worked tirelessly, almost literally to his last breath, to do the one thing that he repeated to every Black crowd he addressed: You must organize. Organize. Organize!

Perhaps his words, which reflect his brilliance, his courage, his ever-growing anticapitalist and anti-imperialist ideology, and his will to bring into being a Black revolutionary world, will feed a new generation who will heed his call.

Mumia Abu-Jamal, author,

We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black

Panther Party and Live from Death Row

Spring 2006

Preface to the 2007 Edition

Forty years ago, on June 17, 1966twelve days before his twenty-fifth birthdayKwame Ture, then known as Stokely Carmichael, was catapulted by the masses of African people in Greenwood, Mississippi, onto the worlds political stage when he reechoed their centuries-old demand for Black Power. It was at that fateful rally in Greenwood that Kwame deployed, for the first time before the worlds media, the full range and power of his organizing capacity, his oratory and charisma. And thanks (no thanks) to the miscalculation of the United States government and media, a refreshingly new, young, black, and revolutionary voice and image was heard and seen for the first time, in every corner of the world.

That Black Power Rally boldly announced to the world, especially to African and oppressed youth, that a new generation had come of political age and had seized control of the worlds political stage, even if only for one brief and shining moment. Kwames words and demeanor, and the crowds response to them and him, signified that a new wave of resistance, rebellion, and revolution had reached critical mass, and that it would take a radically different form. The effect was catalytic.

Five years later, in 1971, Random House published Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism, thanks to the intervention of Toni Morrison, who had been Kwames English professor at Howard University and was at the time an editor at the press, and to the editorship of Ethel Minor, Kwames secretary and advisor in the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party (BPP), the Democratic Party of Guinea (DPG), and the All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party (A-APRP). This seminal collectionof Kwames speeches and writings from 1965 to 1971 was published, according to Ethel, in order to document Kwames consistent growth and development as a revolutionary activist and theoretician. But, Ethel offered, perhaps more important than summarizing the ideological history of a controversial black leader, this book also serves to some extent as the history of the Black Movement during that [period].