SOLAR CATACLYSM

How the Sun Shaped the Past and What We Can Do to Save Our Future

Lawrence E. Joseph

To Phoebe, the sunshine of my life, and Milo, the star of my solar system

Contents

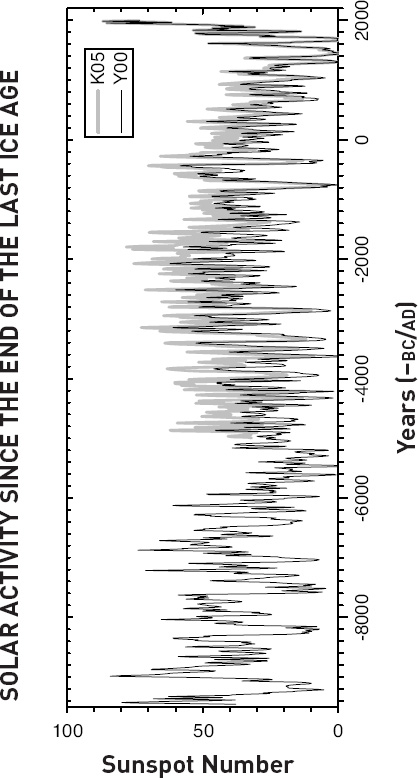

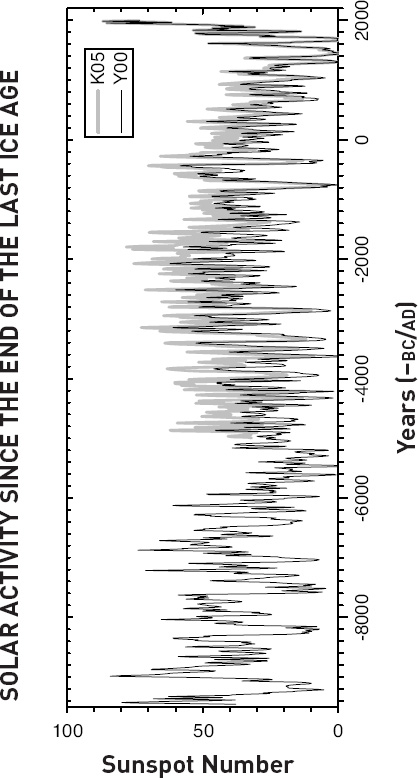

Did you ever find yourself staring at something for no good reason? Cant take your eyes off it even though you really have no idea why? Nerd that I am, I recently became fixated on a graph of the Suns activity over the past 12,000 years or so, from the end of the most recent Ice Age on up through present day. The graph is from A History of Solar Activity over Millennia, by Ilya G. Usoskin of the Sodankyl Geophysical Observatory in Oulu, Finland. As you can see from the facing page, its not much to look at, no fetching fractals, no graceful curves, just the quirks and jerks of some lifeless supermolten fusion behemoth 93 million miles away. One hundred and twenty centuries of solar boom and bust compressed into a single piece of paper turned sideways. After way too many hours of blinking uncomprehendingly, I taped the graph to the front of my computer printer, right next to the yellow Post-it note that says, My Dad is the best Dad in the univers!!!!!a gift from my then-seven-year-old daughter, whose spelling, I must admit, was slow to embrace the silent e.

Phoebes little love note cast the solar activity graph in a whole new light. After confirming that Usoskins diagram is not some one-off outlier, but in fact genuinely reflective of other respected work in the field, I came to realize that the Suns history is, after all, our history as well. For all intents and purposes, it is our only power source, our life-giving energy supply. Nearly every aspect of human existence is susceptible to changes in the Sunin the long term due to climate change, in the short, utterly abrupt term due to the possibility of solar blasts causing massive blackouts, plus many other events, disruptive and benign.

My Moody Sun Hypothesis holds that nothing, including sunshine, is exempt from the laws of change. Random fluctuations in the Suns behavior shape the course of history, affect our daily life, and determine our future in both subtle and cataclysmic ways. Our star is surprisingly changeable, moodier, in a sense, than most of us, scientists and nonscientists alike, had ever assumed. Each time the Sun erupts, goes dormant, or mixes up the spectral composition of its radiation, our environment changes, and, in one way or another, so do we. However, it is crucial to note that the Moody Sun Hypothesis is not of the deterministic ilk. Our fortunes, collectively and individually, are not anchored to the Suns ups and downs. We simply respond to changes in its behavior with our ingenuity and survival instincts. The Sun is always a factor but rarely our master. We are not its slaves. (For more on the Moody Sun Hypothesis, see the Special Note that follows this introduction.)

Just how intimately our destiny is intertwined with that of our sustaining star was brought home to me while I was sitting in a sunny little park at the foot of Broadway on the southern tip of Manhattan, a few dozen yards from where General George Washington once surveyed New York Harbor to protect it from the British. Neither Washington nor I nor anyone else would ever have been nearly so interested in that particular vista had it not been for a bizarre quirk in the Suns behavior at the end of the most recent Ice Age. Look back to the very beginning of Usoskins graph, starting around 12,000 years ago. Thats when temperatures soared due to a wicked spike in solar activity. Picture the moment some 12 millennia ago when the Hudson River, frozen solid for thousands of years, finally gave way. A trillion tons of ice melted into a mighty flood that inundated the isthmus known as the Verrazano Narrows and carved out the canals that now connect New York Harbor to the Atlantic Ocean. Had the Sun never melted the most recent Ice Age, New York Harbor might still be a freshwater lake, and would definitely never have become the grand ocean gateway for immigrants and commerce that made the city one of the greatest in the world.

Second in magnitude only to the giant postIce Age leap in the Suns activity is the solar surge that began in the middle of the 19th century and that continues today. What if solar activity had instead troughed in the mid-1800s, and temperatures fell, not rose? New York Harbor just might have frozen up again, meaning that New York City would be landlocked for much of the year; no Big Apple, just a minor municipality. No Verrazano Bridge from Brooklyn to Staten Island for John Travolta and his pals to clown around on, and fall to death from, in Saturday Night Fever. Maybe the movie would never have been made at all.

The Sun also shares credit for the fact that the best-ever Brooklyn film was shot in English, not Norse, the language of the Vikings. During the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries, the first European immigrants to what is now called North America did succeed in establishing settlements during the Medieval Warm Period. The heyday of the Norse, which lasted roughly from AD 800 to about 1200, was not only a byproduct of such social factors as technology, overpopulation, and opportunism. Their great conquests and explorations took place during a period of unusually mild and stable weathersome of the warmest four centuries in the previous 8,000 years, writes climate anthropologist Brian Fagan in The Little Ice Age. But then solar activity and terrestrial temperatures plummeted during the Little Ice Age, roughly 1300 to 1750. This drop had a profoundly chilling impact on the settling of the New World. The failure of the Norsemen to establish permanent colonies on our continent is less the result of any military, sociological, or cultural lapse than of the fact that formerly passable reaches of the northern North Atlantic became choked with ice for much of the year, thus preventing the seafarers from crossing the seas readily. Vinland, as the Vikings had dubbed their Newfoundland colony, grew too cold to cultivate grapes, from which they made wine (vin). Without profits to be made from exporting wine back to Scandinavia, the dangerous trip was no longer worthwhile. As temperatures dropped during the Little Ice Age, so therefore did seafaring latitudes, favoring balmier climes. Colonizing power shifted southward to the British Isles, Portugal, and Columbuss Spain, essentially enabling those societies to reproduce themselves in the New World, unlike the barren intercourse of their Scandinavian forerunners. Thus it was George Washington, of English heritage, and not some descendant of Leif Eriksson, who ultimately led our nations war of independence from overseas control.

The Moody Sun Hypothesis applies to the future as well as the past. The exploration and colonization of new worlds is just as susceptible to solar output variations today as it was a millennium ago. Astronauts are particularly vulnerable to radiation storms issued by the Sun, much as the ancient mariners were exposed to storms at sea. Both respond in pretty much the same way: hunker down and wait out the storm. But while the Vikings were frozen out of their destiny by the Little Ice Age dip in solar activity, a lull in solar activity would suit space travelers just fine. The fewer the sunspots, and the less powerful they are, the better the prospects for exploring and settling the Moon and Mars; relative space-weather calm is required for establishing dependable lifeline links between Earth and space colonies. A spike in sunspots can scramble long-range plans terribly, as happened in 1977, when Skylab 4, a precursor of todays International Space Station, was disabled when abnormally high solar activity caused Earths atmosphere to heat up and expand. This increased the frictional drag on the satellite, causing its systems to malfunction. Fortunately, no astronauts were aboard at the time. The damage was irreparable, and Skylab 4 eventually fell out of the sky in 1979. This premature demise dealt a blow to NASA, which had expected the little space station to be the first port of call for the Space Shuttle program, when it was launched in the 1980s.

Next page