FLYING IN SUPPORT OF THE GERMAN LUFTWAFFE

Frank Joseph

PART I: WESTERN EUROPE

CHAPTER 2: 45

CHAPTER 3: 57

PART II: EASTERN EUROPE

CHAPTER 4: 73

CHAPTER 5: 83

CHAPTER 6: 95

CHAPTER 7: 117

CHAPTER 8: 141

CHAPTER 9: 159

PART III:THE MIDDLE EAST

CHAPTER 11: 195

CHAPTER 12: 203

PART IV: ASIA

CHAPTER 13: 209

CHAPTER 14: 215

CHAPTER 15: 257

CHAPTER 16: 269

The Luftwaffe fights today on many fronts-from the Arctic Circle to the Bay of Biscay and the North African desert; from far out over the Atlantic Ocean to the Volga. But we are not alone. The skies are illuminated by the different national colors of other peoples who share our epic struggle for the common defense of European civilization.

-Hermann Goering, February 2, 79431

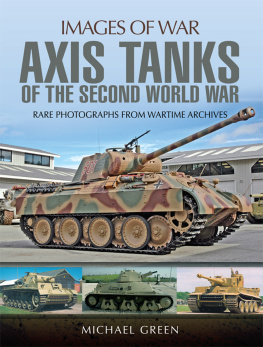

Although countless books and magazine articles describe virtually every aspect of German air power in World War II, their millions of readers are mostly unaware that the Luftwaffe fought in concert with a broad variety of foreign air forces across Europe and Asia. Benito Mussolini's partnership with the Third Reich is well known, but his Regis Aeronautics is usually dismissed as having been too weak and ineffectual for interest. So too, Japan's contribution to the Axis is popularly understood, although beyond common familiarity with the carrier-based attack on Pearl Harbor; and the Zero fighter plane's enduring reputation, little is known, even to serious students of the Pacific War, about the Imperial Japanese Army or Naval Air Forces.

A general lack of appreciation for their significance stems from the pitifully few books devoted to the air arms of either Fascist Italy or Imperial Japan. Far fewer books even go so far as to mention the contemporaneous air forces of Spain, Vichy France, or Hungary, to say nothing of Slovakia, Thailand, and Manchuria. Nor were the air forces operated by these and other Axis nations the miniscule, insignificant military services readers may assume. Close examination of their histories uncovers a hitherto undisclosed, unsuspected panorama of World War II that throws a whole new light on the conflict.

We learn, for example, that the Romanians developed and flew their own interceptor, which capably defended the vital Ploie~ti oil fields against Anglo-American heavy-bombers. Finnish pilots, invariably outnumbered in the air by their Soviet opponents, ranked among the highest-scoring aces of all time. Far from having been saddled with an obsolete air force, the Italians made the world's first cross-country jet flight in 1941, and their Macchi Greyhounds and Centaurs bested both British Spitfires and U.S. Mustangs.

Contrary to Allied wartime portrayals, not every nation fighting at the side of the Third Reich was headed by a Nazi regime, nor even sympathetic to National Socialism. Croatia, Italy, and Slovakia had Fascist or Fascist-style states aligned with Germany. Hungary went Fascist in late 1944, but had been preceded for most of the war by the regency of an arch-conservative anti-Fascist, Miklos Horthy. Monarchies reigned over Bulgaria, Romania, Manchuria, and Japan, while an authoritarian republic ruled Thailand. The parliamentarians of Finland's constitutional democracy wanted as little to do with Adolf Hitler as possible, and rejected his plea to advance their armed forces beyond reclaimed Finnish soil previously annexed by the Soviets, thereby losing the Battle of Leningrad for both Germany and Finland. Rightist governments in France and Spain under Philippe Petain and Francisco Franco, respectively, allowed volunteers to join the Wehrmacht, but refrained from formally allying themselves with the Axis.

These and many thousands of volunteers from the occupied and neutral countries made up the German Luftwaffe's foreign comradesin-arms. Not all shared the same dream. Idealists saw Operation Barbarossa-the code name for Adolf Hitler's June 22, 1941, invasion of Russia-as the most historically significant, unique opportunity for defending all Europeans from otherwise certain destruction and slavery, a struggle that would make possible a new Golden Age of racial unity and cultural greatness. Blinkered nationalists cared not a fig for their fellow Europeans but fought on the Eastern Front entirely for their own particular lands, and were absolutely blind to the necessity of continental cooperation. Others regarded the conflict only as a means to regain lost territories and/or obtaining new ones. Conquest in the East would simultaneously eliminate Stalin and create Lebensraum ("living space") for continental over-population, while providing Europe's new breadbasket.

For all their disparate motivations and agendas, what these strange bedfellows shared in common was the will to extirpate the Soviet colossus growing ever more powerfully next door. Some had first-hand experience with Communism in practice, when Bela Kuhn seized power in post-World War I Hungary, or Lenin sparked a bloody civil war throughout Finland during the 1920s, followed the next decade by another civil war that tore Spain in half. Since then, the Red Army had mushroomed into the largest military phenomenon on Earth, and was universally perceived as a common threat to every European people. Tens of thousands of them-from Iberia to the Balkans-had already died in Soviet-sponsored upheavals long before Operation Barbarossa was launched.

Like the Regia Aeronautica, most Axis air forces operated independently from, but in concert with, the Luftwaffe, although all of them were more or less indebted to Germany for training and, at least partially, leadership and equipment. The distant Manchurians flew Junkers-86 medium-bombers, and the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force's Kawasaki Tony interceptor began as a Heinkel-100. Particularly surprising were the numerous crucial roles undertaken by the crews of these relatively obscure air forces during the war, and how that global struggle sometimes hinged on their performance.

To be sure, influence on the development and even the outcome of World War II was all out of proportion to their low numbers and outdated aircraft. Operating cast-off Brewster Buffalo fighters, sometimes against 12-to-1 opposition in the skies over Leningrad, Finland's Eino Juutilainen claimed 94 confirmed "kills;' though his actual score was well over 100. Even little Slovakia produced world-class aces, such as Jan Reznak, who downed 32 enemy aircraft and destroyed dozens more on the ground.

Meanwhile, Hungary's Laszlo Molnar and Bulgaria's Petar Botchev accounted between themselves for literally thousands of Red Army troops, armored vehicles, and supply trucks. Their victories are no less unacknowledged than those scored by France's Vichy Air Force, which turned back an Allied invasion of West Africa and effectively defended Madagascar against overwhelming odds for half a year. Estonians, Latvians, and even anti-Communist Russians operated their own squadrons on the Eastern Front, where they regularly spoiled Soviet initiatives. During the struggle for Stalingrad, Croatian pilots averaged more than 20 missions per day, until they were the last Axis pilots still flying over the embattled city. While Manchurian airmen rammed their planes into some of the first American B-29s lost during World War II, Japanese interceptors defeated America's early strategic bombing offensive against their country, and USAAF P-38 Lightnings fell under the guns of Thai pilots.