The Other Side of Terror

The Other Side of Terror

Black Women and the Culture of US Empire

Erica R. Edwards

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2021 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Edwards, Erica R. (Erica Renee), author.

Title: The other side of terror : Black women and the culture of US empire / Erica R. Edwards.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020055481 | ISBN 9781479808427 (hardback) | ISBN 9781479808434 (paperback) | ISBN 9781479808403 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479808410 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : American literatureAfrican American authorsHistory and criticism. | American literatureWomen authorsHistory and criticism. | Feminist literatureUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | Terrorism in literature. | Imperialism in literature. | Racism in literature. | African Americans in literature. | Literature and societyUnited States.

Classification: LCC PS153.N5 E345 2021 | DDC 810.9/928708996073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055481

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For the insurgent ground

And in memory of Hampton Gilmore Edwards

Contents

Color illustrations appear as an insert following page 182.

What Was to Come

Velma Henry, the protagonist of Toni Cade Bambaras 1980 novel The Salt Eaters, is positioned on a stool, in the center of a healing circle, for nearly the entire duration of the 296-page text. She is in the hands of Minnie Ransom, who wants her to be well and who wants her to want to be well. But it is a decade after 1968, that bloody year of assassinations, that soaring year of Black aesthetics and Black studies, that helter-skelter year when the familiar world spun out of control. She could be a domestic terrorist, or she could be the hostage of foreign terrorists, or she could just be a Black woman at work. Velma can imagine all of these possibilities alongside the possibility that she might return to her right mind only to shoulder the burden of life right back on this side of terror, where to be liberated gives way not to the glory of achievement but to a pain that is even deeper and even more mind-scrambling. It could be that nuclear disaster, the continued failures of Black politics, ever-resurgent white supremacy, or old-fashioned warfare will finish the work of Velmas suicide attempt or simply give way to new threats. She does not yet know it, but what had driven Velma to the oven... was nothing compared to what awaited her, was to come; her next trial might lead to an act far more devastating than striking out at the body or swelling gas (29394). For now, Velma Henry sits on the healers could-be terrorist / could-be hostage stool. She sits throughout a novel that Bambara, a master of short fiction who devoted her precious latter years to filmmaking, wrote in part to satisfy a cultural marketplace that kept Black womens literary labor, even in its most radical expressions, on spectacular display. To study with care Velmas position at the intersection of liberation, terror, and work is to take up the task of studying the full range of positions that Black women occupied in the culture that has justified and spread US imperialism throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Throughout this book, I call that culture the culture of US empire.

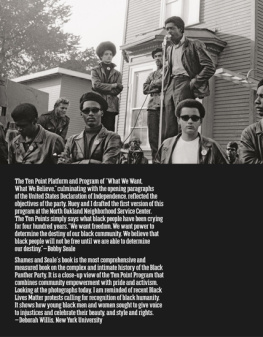

In this book, I analyze the relationship between race, gender, terror, and the making of US empire through the late Cold War technologies of counterinsurgency. I argue that throughout what I call the long war on terror, the culture of contemporary empire-building through the technologies of war, surveillance, and detentionthe culture of keeping America safe, of securing our borders, of defeating terrorismhas transformed African American literature as a social field. The imprint of domestic and foreign counterinsurgency on Black womens writing in particular at a time when the community of Black women writing became, in Hortense Spillerss oft-cited words, a vivid new fact of national life, was unmistakable in the clarity of both its inspiration (the blood spilled in Boston, Atlanta, Detroit, El Salvador, Guatemala, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Palestine, and Iraq in the name of North American security) and its imperative (to create and communicate ways of defending against what the US state was calling defense throughout the long war on terror). The long war on terror is the large-scale, multipronged campaign of counterterrorism that escalated during the late Cold War period against organizations deemed domestic terrorist threats, such as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense and the Black Liberation Army. Starting in 1968, I map the transformations of Black womens expressive culture against the campaigns of counterterrorism at home and abroad, beginning with COINTELPROs efforts to contain Black radicalism and radical Black feminism and proceeding through Reagan-era counterinsurgency, and the wars in Iraq. If US empire-building throughout the long war on terror demanded a shift in racial gendered power, with Black women coming to occupy a central place in the late twentieth-century imaginary and iconography of global power, Black feminist writers predicted and tracked that shift. More than that, they crafted ways of surviving it. This is a story of state power at its most devious, at its most absurd, and, at the same time, a literary history of Black feminist radicalism at its most trenchant. If I follow Bambaras lead, the term incessant war might serve just as well as long war. The old-timers who crowd around Velma in her healing room in The Salt Eaters are Garveyites, Southern Tenant Associates, trade unionists, Party members, Pan-Africanists, united by their memory of night riders and day traitors and the cocking of guns (15). They are those for whom the sound of a door clicking into its jamb holds within it the sonic terror of anti-Blackness spinning through the generations, those who lack the luxury of literary critics stubborn preference for discrete periods. They might know what was to come after all, and have an answer for it.

Black feminist expressive culture has taken as one of its central motives deciphering the tracks between anti-Black terror and the operations of late- and postCold War counterinsurgency, which have increasingly depended on Black loyalty to country, Black statecraft, what Gwendolyn Brooks decades ago referred to sneeringly as the government men with pretty brown faces, to spread the fiction of democracy around the world, in sentences of justification and with actual weapons of war.

Black Women and the Culture of US Empire

To read contemporary Black womens writing in isolation from the historical context of the long war on terror is to ignore the ways that the insurgent textuality and activist labor of Black feminist literary culture wrestled with the literal terms of the new world order. While studies of Black feminist literature and the wider field of Black womens writing have insightfully pointed to writers critiques of intraracial hierarchies of gender, class, and sexuality, we have yet to fully grasp the ways that Black womens writing refracts the fantasies and applications of US foreign policy, particularly as these emerged in the context of anti-Arab counterterrorism and police actions and proxy wars in the Caribbean and Central America. But as recent work by M. Jacqui Alexander, Carole Boyce Davies, Shaundra Myers, Randi Gill-Sadler, Patricia Stuelke, Roderick Ferguson, Cheryl Higashida, Grace Hong, and others has suggested, when we cast our studies of Black womens writing in the context of the new world order that was shifting the geopolitical pressures on writing itself, we better understand the nature of power and its relation to race and gender difference.