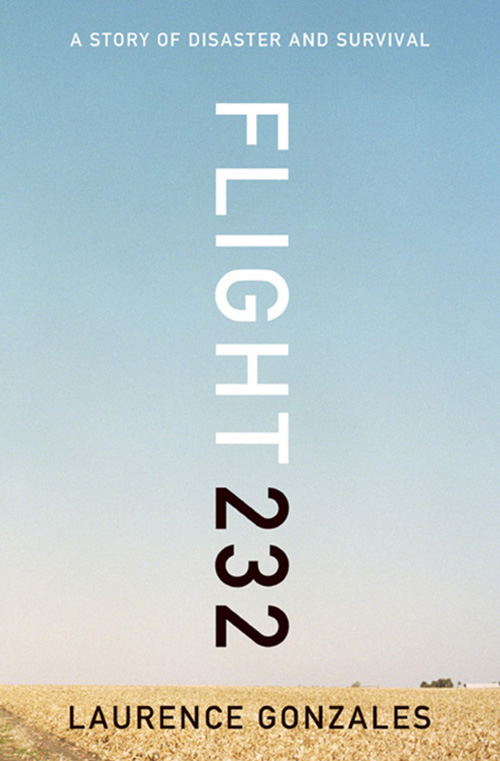

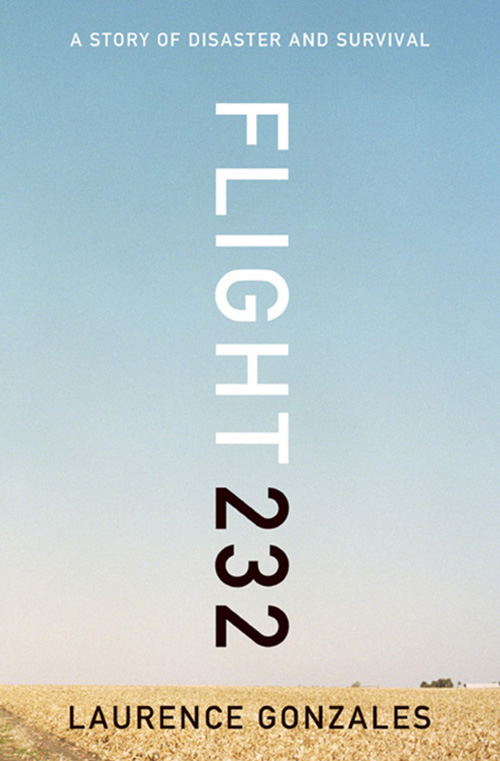

FLIGHT

232

A STORY OF DISASTER AND SURVIVAL

Laurence Gonzales

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2014 by Laurence Gonzales

All photos courtesy of the

Iowa Department of Public Safety

unless otherwise noted.

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Daniel Lagin

Production manager: Devon Zahn

ISBN 978-0-393-24002-3

ISBN 978-0-393-24414-4 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To My Son Jonas

ALSO BY LAURENCE GONZALES

NONFICTION

House of Pain: New and Selected Essays

Surviving Survival: The Art and Science of Resilience

Everyday Survival: Why Smart People Do Stupid Things

Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why

One Zero Charlie: Adventures in Grass Roots Aviation

The Heros Apprentice: Essays

The Still Point: Essays

FICTION

Lucy

FLIGHT 232

overlooking Sioux City, Iowa. He had taken the afternoon off to see a movie with his wife Jody and their two daughters, Laura, seven, and Jenna, five. Not only would he enjoy the warm nostalgia of seeing the original Walt Disney version of Peter PanYou can fly! You can fly! You can fly!but he and his family could escape the heat. Although the temperature on that Wednesday in July was only 80 degrees, a storm two days earlier had left the humidity steaming off the fields of corn and soybeans and made the day feel much hotter.

Tall and lanky, a youthful thirty-seven, Clapper, who taught theology, had an aspect both serious and gentle. That put people at ease and made him more effective as a college professor. It also helped him in his role as the chaplain for the 185th Tactical Fighter Group of the Iowa Air National Guard, which had its headquarters at the Sioux City airport. Clapper parked the car and stepped out with his wife and daughters. As the family crossed the hot paving toward the theater at the Southern Hills Mall, a sudden roaring whine turned Clappers gaze skyward. Silhouetted against a bright sky, the dark form of a jumbo jet,. Clapper thought, Jumbo jets dont land at Sioux City. As he watched, stilled, with one of his little girls hands in each of his, the plane crossed Highway 20 and Morningside Avenue and flew over Sertoma Park. It then sank out of sight. His family was waiting, but for some reason Clapper continued to watch. They stood that way, this tableau of people beneath the sun, for what seemed a long time but was in reality only seconds. Then a reef of black smoke rose and coiled from beyond the industrial buildings, and a low, almost imperceptible, rumbling vibration shook the pavement. Clapper felt his face go clammy.

He led his family back to the car. His children may have been asking what was going on, but it was as if hed gone deaf. He opened the car and put the key in the ignition. He turned on the radio. Music, static, voices. Then an announcer, with grim solemnity, said that he had received an unconfirmed report that a plane had crashed. Clapper felt a crushing sensation in his chest. He started the car.

Jody, Laura, Jenna, get in the car, he said. His wife buckled the girls in, and Clapper fled the mall for the nearby entrance to Interstate 29. He drove south toward the airfield. Perhaps five minutes had elapsed since he saw the smoke, yet already a state trooper was blocking the exit to the field. Clapper pulled up, wondering how the police had arrived so soon. He rolled down his window and showed the officer his military ID. I am a chaplain and need to be at the crash scene, he said.

I dont care, the officer said. No one is getting off here.

Seeing that arguing would not work, Clapper pulled the car another hundred feet down the highway and put it in park. Jody, he told his wife, take the kids back to the theater. Theres nothing you can do here. Ill get my own ride back home. Then Clapper started running down the highway toward the column of grimy smoke that rose into the clear blue sky.

In Great Britain jumbo jet refers exclusively to the Boeing 747. In the United States the term commonly means any wide-body airliner.

M artha Conant traveled regularly for her job with Hewlett-Packard in Denver. On that Wednesday, she was on her way to Philadelphia to work with a client. She didnt even look at her ticket until she was at the airport. She had been assigned a seat in the last row. She checked the display boards and saw that she could wait a couple of hours for a nonstop flight instead of this one, which was making a stop in Chicago. After thinking it over, she decided that she could get some work done on the plane. She kept her reservation for United Flight 232. The date was July 19, 1989.

Conant took the second seat in from the port aisle in the center section at the back of the plane. She wore a black skirt and a pink sweater. She carried a briefcase and a purse. Conant anticipated people milling around the bathrooms behind her as flight attendants bustled about with their carts in the galley. She resigned herself to a few unpleasant hours and decided to lose herself in her work. Martha Conant opened her briefcase.

She didnt pay much attention to the preparations for departure and the takeoff: a routine flight among many routine flights. She glanced up once or twice at the in-flight movie, a documentary about the Kentucky Derby or the Triple Crownsomething about horseracing narrated by a sportscaster named Jim McKay. The in-flight meal was a , as United Airlines called it that summer: a plastic basket with a red-and-white-checked napkin in which were nestled greasy chicken fingers, a package of Oreo cookies, and a paper cup with a few cherries in it. Conant had just eaten one of the chicken fingers when an explosion shook her from her reverie. Her first thought was that a bomb had gone off, and her heart went into her throat. Susan White, the young flight attendant in the port aisle, went to her knees with an armload of drinks as the plane slewed to the right. Conant felt the tail drop out from under her as the plane began climbing.

At forty-six, Conant had curly auburn hair, brown eyes, and an endearing smile. She had hoped to have a good portion of her life ahead of her as well, yet she realized that she was likely going to die that day. Fear contracted within her torso like a black spider. After a minute, though, a steady male voice came over the loudspeakers and explained that they had lost the number two engine, the one that ran through the tail above and behind Conants head. But, said the voice, the plane had two other engines, one on each wing. They could proceed to Chicago at a slower speed, a lower altitude.

Conant tried to think. She tried to convince herself of the reassuring story Dudley Dvorak, the second officer, or flight engineer, had broadcast throughout the cabin. Shortly after the explosion, the four flight attendants in her part of the plane disappeared into the galley to whisper among themselves. Now they emerged again with their carts and resumed serving drinks. Five rows ahead of Conant, Paul Olivier, a businessman who was also the mayor of Palmer Lake, Colorado, was surprised that the flight attendants continued serving. He would later recall Susan White, who would turn twenty-six that October but looked like a teenager. She was just shaking, said Olivier, visibly shaking. She asked if he wanted something to drink, and he ordered a vodka. White opened the liquor drawer on her cart. It was neatly lined with mini liquor bottles, all arranged by type. She selected a vodka, placed it on his table with a glass of ice, and closed the drawer. Make it a double, said Olivier. When White pulled out the service drawer the second time, her shaking hand seemed to have a mind of its own, and the little liquor bottles scattered all over the floor. On her hands and knees, she gathered up the bottles as they rolled around on the carpet. Once she collected herself and her bottles, she stuffed them into the drawer any way theyd fit and slammed it shut. Observing her rattled state, Olivier told White, It really looks like

Next page