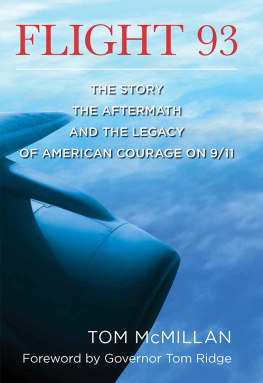

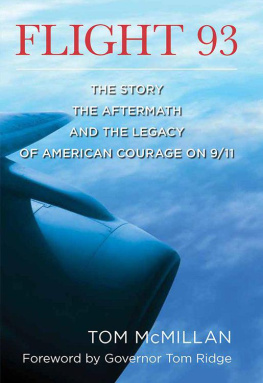

O N S EPTEMBER 11, 2001, passengers were not encouraged to assist the crew in the rare case of an airplane hijacking. They were actively discouraged. Passengers were to be mollified with food and drink, with vague information and nebulous assurance. That all changed with the brave insurrection of the passengers and crew members aboard United Flight 93, which was hijacked en route from Newark, New Jersey, to San Francisco. Having learned about the horrific unfolding of the mornings events from a series of telephone calls, and given time to act, those aboard the jetliner thwarted an attempt by the terrorists to crash the plane into a Washington landmark of government or security. As Americans, we believed we had control over our lives inside secure borders. On the day we lost that control, the forty passengers and crew members attempted to regain it. And thus, they won the first battle in the new war against terrorism.

We believe those passengers on this jet were absolute heroes, Robert S . Mueller III , director of the FBI , said at a memorial at the Flight 93 crash site outside of Shanksville, Pennsylvania. And their actions during this flight were heroic.

Many crucial questions about the final minutes of the flight remain unanswered, but it is clear the passengers and crew acted with heroic defiance. They accomplished what security guards and military pilots and government officials could notthey impeded the terrorists, giving their lives and allowing hundreds or thousands of others to live.

Flight 93 redefined sacrifice for me, President George W. Bush told The Washington Post. And if a handful of people will drive an airplane into the ground to save either me, or the White House, or the Congress, you know others in our country will make the sacrifice to save us down the road.

I covered the crash of Flight 93 as a reporter for The New York Times, along with my colleagues Sara Rimer and Jo Thomas. When the idea of a book was proposed to me, I hesitated. There is no worse job for a journalist than having to speak with grieving families. Nothing you say can provide any solace. And in these disconsolate times, the last thing family members want is a notebook or camera thrust into their faces. Then I reconsidered. It seemed that someone ought to write about these remarkable people. Many years from now, their brave uprising will surely be remembered as a defining moment in American history.

This book was meant to accomplish three thingsto recreate the actions aboard Flight 93 in as much detail as is known, to commemorate the forty passengers and crew members, and to attempt to understand how Ziad Jarrah, the hijacker pilot, became radicalized to the point of suicidal terrorism. It was important to write about all the pilots, flight attendants and passengers. While there is no doubt about the heroism of the four or five passengers who became well known from their phone calls, it would be reckless to assume they were the only ones who acted heroically.

The term that keeps coming into my mind is esprit de corps, said Lisa Beamer, whose husband, Todd, was a passenger on Flight 93. There were probably some people who hatched the plan and initiated it to other people, but I dont think there were people sitting back, going, Please dont jump on the hijackers, they might explode. Ive felt strongly all along that people did what they could do, whether it was pushing a cart down the aisle, or boiling water, or comforting others, or cheering them on.

For this book, I contacted the families of each passenger and crew member. All agreed to speak with me; in the end, only one did not. I also contacted friends and co-workers of each passenger and crew member. And, after weeks of trying, I reached by phone, in Lebanon, the family of Jarrah, the hijacker pilot. Upon conducting more than three hundred interviews, I came to realize that the passengers and crew members aboard Flight 93 were not ordinary citizens placed in an extraordinary situation, as they have often been portrayed. As a group, these were people who were on top of their game, who kept score in their lives and who became successful precisely because they were assertive and knew how to make a plan and carry it out. The people aboard the plane had varied skills. Not everyone could rush the cockpit, but I am convinced that each person offered whatever resources he or she had available in the final moments of the flight. I heard tapes of a couple of the phone calls made from the plane and was struck by the absence of panic in the voices.

As could be expected with an early-morning flight, at least fifteen people were inadvertent travelers on Flight 93, having made travel plans at the last minute or having switched from another flight. One of the passengers, William Cashman, was an ironworker who helped build the World Trade Center. Another passenger, Donald Peterson, ran an electric company whose motors were used, according to his son, to operate the backup water-pressure system in the Trade Center. Kristin White Gould was a writer from New York and a descendant of one of the most influential Pilgrims on the Mayflower. Donald F. Greene, who had a pilots license, was the son of a woman whose family founded Saks Fifth Avenue. His stepfather invented a device to warn against stalling, which is standard equipment on the worlds aircraft.

There were connections, unknown on September 11, among a number of people aboard Flight 93. Of the passengers who made telephone calls, Todd Beamer and Mark Bingham both graduated from Los Gatos High School in northern California. Mark Bingham, Jeremy Glick and Tom Burnett were all presidents of their college fraternities. Cathy Stefani, the mother of passenger Nicole Miller, was a classmate of Captain Jason Dahl at Andrew Hill High School in San Jose, California. Jeremy Glick and Linda Gronlund both lived on Greenwood Lake that straddled the border between New York and New Jersey.

Richard Guadagno, who managed the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge in Eureka, California, was a federal agent who had been trained in close-quarter fighting. A handful of passengers had practiced martial arts. Several were emergency medical technicians. The lone married couple aboard Flight 93, Donald Peterson and Jean Hoadley Peterson, devoted their later lives to crisis counseling. CeeCee Lyles, a flight attendant, was a former policewoman. There were a number of people aboard who were trained to be calm and decisive in times of stress.

While it is futile, even arrogant, to think that the existence of forty individuals can be wholly compressed into the pages of a book, I have attempted to get beyond the grim numbers of this tragedy and to portray the resolve and quiet dignity of human lives given so selflessly and heroically.

Just the thought of people on an airplane saying, Were not going to let these guys get away with this, makes you want to live your life better than you had been, said Ed Figura, a fifty-five-year-old salesman who visited the crash site a month after Flight 93 was hijacked.

Three days before Christmas, a British man named Richard C. Reid boarded American Flight 63 from Paris to Miami and attempted to ignite his shoe with a match. His shoes were packed with plastic explosives, authorities said. A flight attendant and passengers subdued the man, and doctors on board gave him a sedative. The plane was safely diverted to Boston. Given the bold lesson of United Flight 93, people knew exactly what to do. No longer would passengers and crew sit idly by while someone attempted to hijack or blow up a plane. No longer would passivity be an expected response to terrorism in the sky.