First published in the UK by John Blake Publishing

An imprint of Bonnier Books UK

Victoria House, Bloomsbury Square,

London, WC1B 4DA

Owned by Bonnier Books

Sveavgen 56, Stockholm, Sweden

www.facebook.com/johnblakebooks

twitter.com/jblakebooks

First published in hardback in 2021

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78946-460-3

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78946-461-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78946-532-7

Audiobook ISBN: 978-1-78946-465-8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design by www.envydesign.co.uk

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Text copyright Stephen Davis 2021

The right of Stephen Davis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright-holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

John Blake Publishing is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

I would like to dedicate this book to my mother Jocelyn, who has always watched the news and bought a newspaper. She set me on the path to a career in journalism.

CONTENTS

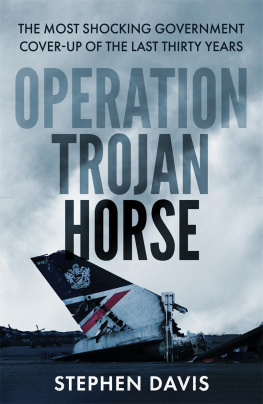

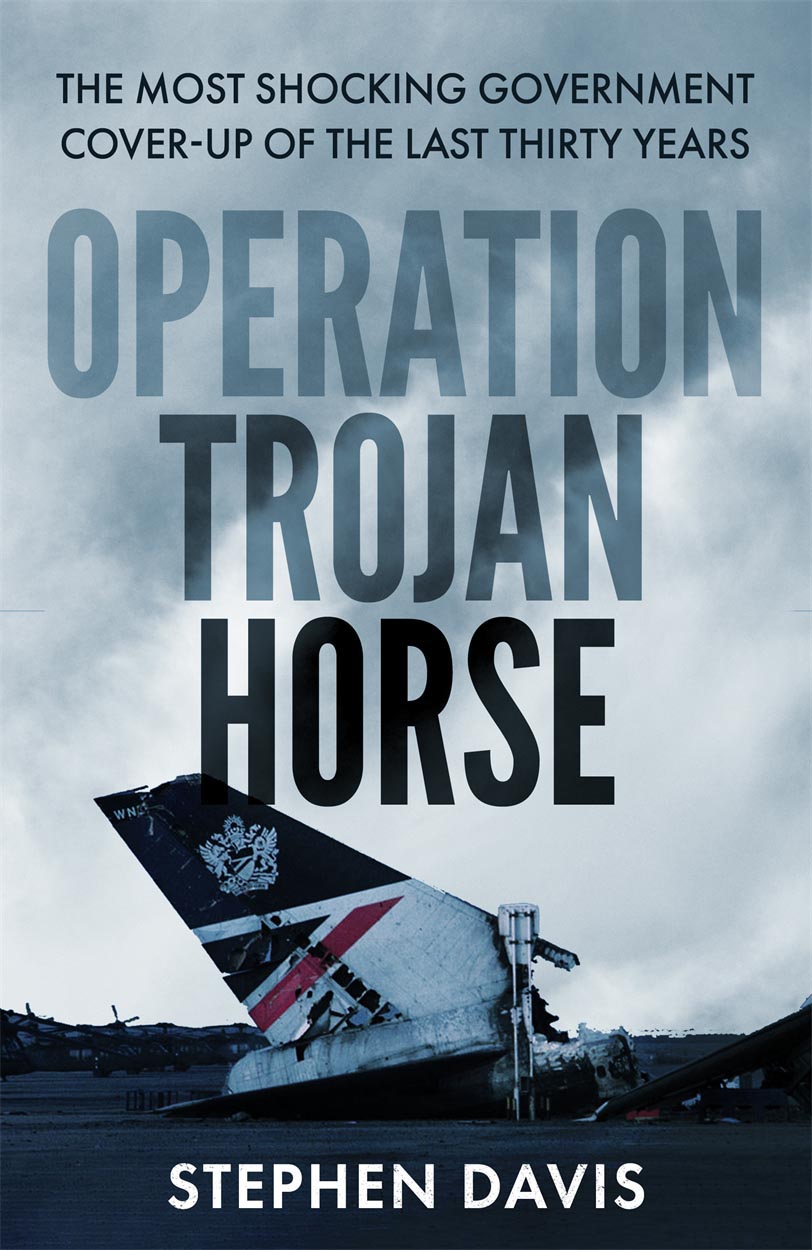

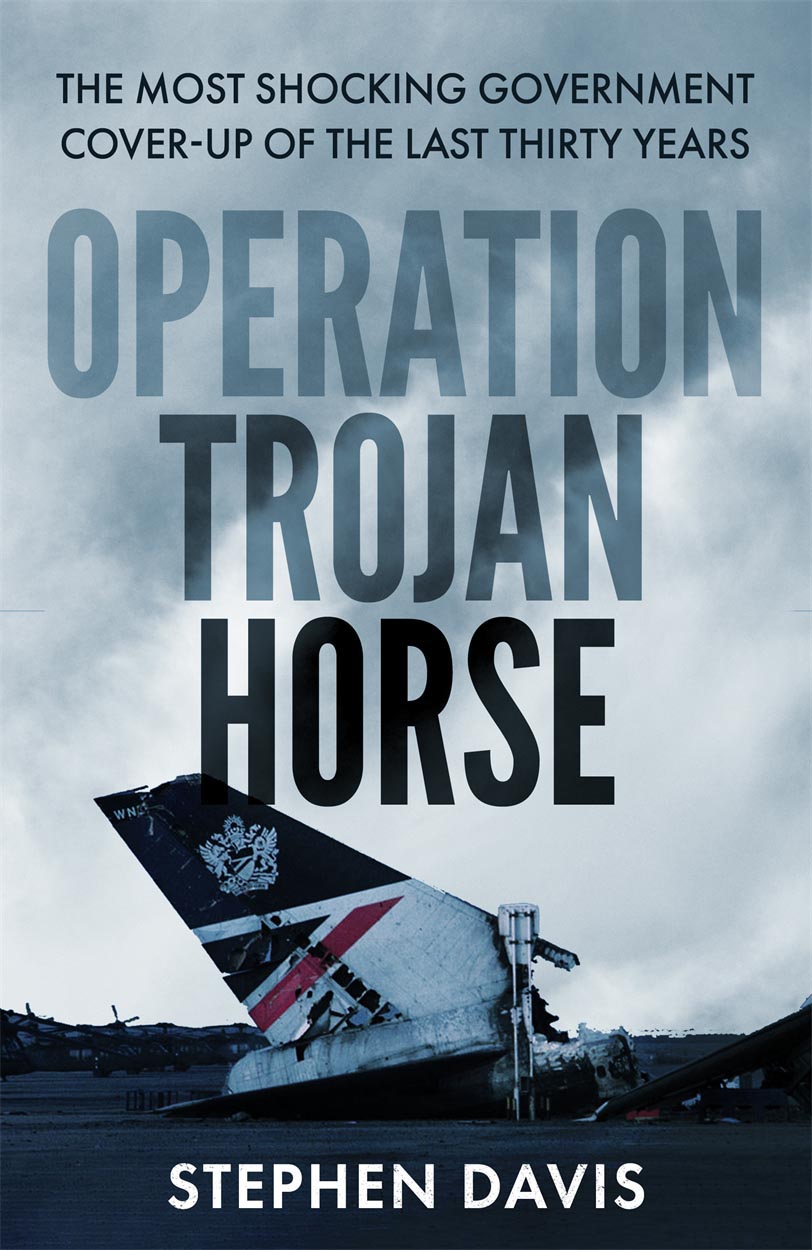

T he shattered tail of a British Airways Boeing 747 sat in inglorious isolation on the runway of Kuwait airport in February 1991 amid the celebrations over the liberation of Kuwait by George H. W. Bushs Desert Storm.

The image went round the world, a reminder of the grim fate of many of those caught up in Saddam Husseins invasion six months earlier.

In the wider shot, you can see the crumpled fuselage of Flight 149, which flew from Heathrow to Kuwait at the start of the invasion and never returned.

The picture was released with a story that quoted military sources. The 747, it said, was destroyed by the Iraqis as they fled in haste before the might of Stormin Norman Schwarzkopf and his allied armour and air power.

No one seems to have asked why the Iraqis, who looted everything of value that they could get their hands on, down to light bulbs and bathroom faucets, would destroy such a valuable propaganda prize rather than simply fly it to Iraq.

The answer is that the Iraqis did not destroy the plane. The BA 747 was destroyed by American fighter planes at the request of the British.

Why, then, blame the destruction on the Iraqis when the sad image of the shattered wing of Flight 149 was shown round the world? Was it to hide the embarrassment of an own goal or was it to cover up something else?

I was working on the news desk of the Independent on Sunday in London when the photo was released and I added it to my growing file on the mystery, a mystery that had begun with a simple phone call.

In August 1990, I had become interested in persistent rumours about Flight 149, after it landed in Kuwait as it was invaded by Iraqi troops.

All the passengers and crew had been taken hostage and were at the mercy of Saddam Hussein.

The British Foreign Office (FO) put out reassuring messages that the passengers were not in any danger. In fact, it was said, they were on a sort of unexpected holiday, drinking cocktails in the sunshine by the pool at luxury hotels.

My caller, a contact, begged to differ. There is something not right about all this, he said, you should investigate. So began a long search for the real story.

The world of 1990 was one in which it was easier to hide the truth. There were no mobile phones to photograph or live-stream events, no social media to contradict official statements. It was a world before Putin and Trump, in which it was still possible to believe that Western democracies would not go to war on the basis of misused intelligence, or that leaders would not lie every day to their citizens.

The investigation that led to this book involved over three hundred interviews in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Denmark, Canada, India, Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand, Iraq and Kuwait. I have had access to previously confidential documentation; the remarkable, unpublished diaries of American and British hostages; and talked to survivors and grieving relatives, lawyers and government officials, politicians and human rights campaigners, soldiers and spies.

Along the way, I have sat in a living room listening to a young woman describe how she repeatedly tried to take her life because she never recovered from her ordeal in captivity; heard a former flight attendant talk of his lifelong battle with crippling fear that ultimately ended his career; heard harrowing tales of rapes, assaults, mock executions and near-starvation conditions; engaged with CIA sources, who, out of conscience, helped me with classified documents; and interviewed soldiers at the heart of the most secret part of the British government who risked their livelihoods and their freedom to reveal the truth behind Flight 149.

INVASION

T he British Airways Boeing 747 was called Coniston Water. Maureen Chappell noticed the name as she stood in line to board the plane and it disturbed her. She was a frequent flier and she seldom bothered to notice the names of aircraft, but this one struck her as odd. She knew that Coniston Water was the lake in Cumbria where great British hero Donald Campbell, the holder of world speed records on land and water, was killed when his boat, Bluebird, flipped over during a 300-mph run. It was a story of disaster and death. Strange name for a plane, she thought. Her daughter Jennifer noticed the name, too, as the family entered the planes front cabin. She was too young to remember Campbell but somehow the name stuck with her as she found her way to her seat. For some reason, it made her feel uncomfortable.

The Chappell family husband John, wife Maureen and children John, fourteen, and Jennifer, twelve were travelling in Business Class. John was returning with his wife to India where he was an electronics systems adviser to the Indian navy. The children were on vacation from boarding school. Jennifer was looking forward to a big party to celebrate her upcoming thirteenth birthday. All her friends in India had been invited. Apart from that, she and John Jr. felt the way they normally did on these long-haul trips: tired, hot and bored.

It was early evening at Heathrow, on Wednesday, 1 August 1990, and Flight BA149 was headed for Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, via Kuwait and Madras. Departure had already been delayed for two hours. Apparently, a fault had been found in the auxiliary power unit, a small engine in the tail that provided air-conditioning. The delay seemed to put everyone passengers and crew on edge. The 747 they were waiting to board, registration number G-AWND, was one of the oldest in the British Airways (BA) fleet, having been built in Seattle some nineteen years earlier. It was also rumoured to have had a rather chickened history an unhappy Jamaican, spurned by his lover, had apparently walked up to the plane as it sat on the tarmac and killed himself by jumping into one of the still-rotating jet engines.

Next page