Contents

About the Book

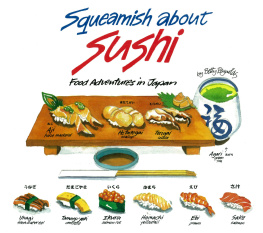

Japan is the pre-eminent food nation on earth. The Japanese go to the most extraordinary lengths and expense to eat the finest, most delectable, and downright freakiest food imaginable. Their creativity, dedication and ingenuity, not to mention courage in the face of dishes such as cod sperm, whale penis and octopus ice cream, is only now beginning to be fully appreciated in the sushi-saturated West, as are the remarkable health benefits of the traditional Japanese diet.

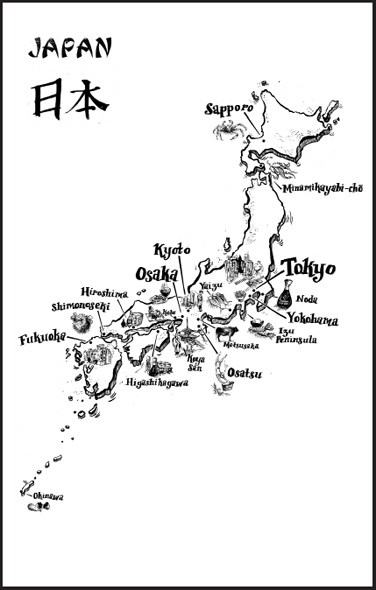

Inspired by Shizuo Tsujis classic book, Japanese Cooking, A Simple Art, food and travel writer Michael Booth sets off to take the culinary pulse of contemporary Japan, learning fascinating tips and recipes that few westerners have been privy to before. Accompanied by two fussy eaters under the age of six, he and his wife travel the length of the country, from bear-infested, beer-loving Hokkaido to snake-infested, seaweed-loving Okinawa.

Along the way, they dine with and score a surprising victory over sumos; meet the indigenous Ainu; drink coffee at the dog caf; pamper the worlds most expensive cows with massage and beer; discover the secret of the Okinawan peoples remarkable longevity; share a seaside lunch with free-diving, female abalone hunters; and meet the greatest chefs working in Japan today. Less happily, they trash a Zen garden, witness a mass fugu slaughter, are traumatised by an encounter with giant crabs, and attempt a calamitous cooking demonstration for the lunching ladies of Kyoto. They also ask, Who are you? to the most famous TV stars in Japan.

What do the Japanese know about food? Perhaps more than anyone on else on earth, judging by this fascinating and funny journey through an extraordinary food-obsessed country.

About the Author

Michael Booth is a travel writer and journalist who contributes regularly to Cond Nast Traveller, the Independent on Sunday and Monocle, among many other publications at home and abroad. His last book, Doing Without Delia, was Book of the Week on Radio 4.

www.michael-booth.com

Also by Michael Booth

Just as Well Im Leaving:

To the Orient with Hans Christian Andersen

Doing Without Delia:

Tales of Triumph and Disaster in a French Kitchen

(also published as Sacr Cordon Bleu)

To Asger and Emil

Chapter 1

Toshi

HA! YOU SO fat you not see your dankon for years! You pants too small. You so fat, sun go down when you bend over!

It was a characteristically abusive and, I should stress, not entirely accurate conclusion to what had started off as a perfectly temperate discussion about the relative merits of French and Japanese cuisines.

I had recently had dinner at the feted French restaurant, Sa.Qua.Na, in Honfleur on the Normandy coast. The chef, Alexandre Bourdas, is a fast-rising culinary star in France and I had innocently remarked on his lightness of touch, and the freshness of his raw ingredients, drawing what turned out to be a rash comparison between his food and Japanese cooking. I knew that Bourdas had worked in Japan for three years, so it didnt seem too outlandish to suggest that his cooking had been influenced by the food he had eaten there.

I ought to have known this would be a red rag to my friend Katsotoshi Kondo.

What you know about Japan food, huh? he snapped. You think you know anything about Japan food? Only in Japan! You can not taste it here in Europe. This man is nothing like Japan food. Where is tradition? Where is seasons? Where is meaning? Tu connais rien de la cuisine Japonaise. Pas du tout! From experience I knew that this sudden switching of languages was a bad sign, as was the pouting. I had to get my retaliation in before he detonated fully.

I know enough about it to know how dull it is, I said. Japanese food is all about appearance, you dont know anything about flavour. Wheres the comfort, the warmth, the hospitality? No fat, no flavour. What have you got? Raw fish, noodles, deep-fried vegetables and you stole all that from Thailand, the Chinese, the Portuguese. Doesnt matter though does it? You just dunk it in soy sauce and it all tastes the same, right? All you need to make good Japanese food is a sharp knife and a good fishmonger. What else is there? Ooh, dont tell me, cod sperm and whale meat. Mmm, got to get me some of those.

I had met Toshi while training at the Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris a couple of years earlier. A tall, austere half-Japanese, half-Korean man in his late twenties, he was wrapped in many layers of inscrutability, but had a subversive, dry sense of humour lurking behind the gruff, Beat Takeshi facade.

While the rest of us would wear our chefs whites for days until we looked like a walking Jackson Pollock, Toshi was always immaculately turned out. His plates were always perfect: his food presented just so, with ample white space surrounding it: his knives always fearsomely sharp. But he had clashed with the French chefs who taught us. They invariably marked him down because he refused to cook fish for more than a few seconds, and he served vegetables with a crunchy bite, rather than soft all the way through as they preferred. This seeded in Toshi a lingering resentment towards the French and their cuisine but still he stayed on in Paris, partly, I suspect, out of a sheer bloody-minded determination to single-handedly educate the locals in the superior ways of Japanese cooking.

The French know Japan food like she know sex, he once told me, pointing to a passing nun.

After graduating, Toshi went to work in a Japanese restaurant in the sixth arrondissement, the kind of thoroughly authentic place virtually invisible from the street but a haven of serenity within that registered only on the radar of Japanese tourists. We kept in touch and met up from time to time to eat and talk food, our get-togethers usually descending into a childish rally of insults.

But this time things ended slightly differently. OK, just shut up, OK? Toshi said, his head disappearing beneath the table as he fished around in his satchel. I have something for you. You stupid, you read.

He handed me a large hardback with a blurry painting of a leaping fish on the cover. Momentarily taken aback, I promised to read it and thanked Toshi. This was embarrassing. He had never given me anything before. It had taken me some time to explain to him the concept of buying a round of drinks, for instance. It was clearly an expensive book too and, though it sounds ridiculous given the times Toshi had ranted at me and called me a no-brain-whitey-gaijin, for the first time, as I held the book on my lap on the bus home, I began to understand how keenly he must have felt the slights from me and our teachers at Le Cordon Bleu.

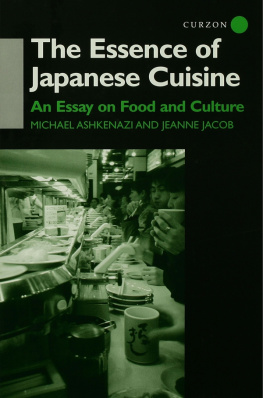

The book was Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, by Shizuo Tsuji, a new edition of the original published in 1979. Introductions by Ruth Reichl, the editor of Gourmet magazine, as well as the legendary US food writer, the late M. F. K. Fisher, served notice that this was no ordinary food book. As I would later discover, it is still the pre-eminent English-language Japanese food reference source, the bible of Japanese cooking for a generation of Japanophile food lovers throughout the world.

This is much more than a cookbook, writes Reichl. It is a philosophical treatise.

There are recipes, of course, over two hundred of them covering grilling, steaming, simmering, salads, deep frying, sushi, noodles and pickling many of the dishes unfamiliar to me but along the way Tsuji also covers everything from the spiritual meaning of rice, to the role of tableware in Japanese cuisine. No Japanese, however humble, would think of serving food on just any old plate, relying on flavour alone to please, he writes. Tsuji emphasises the fundamental importance of the seasons in Japanese food: in Japan ingredients with a particularly brief seasonal window are often celebrated with a quasi-spiritual verve by cooks and diners. I learned, too, that the Japanese employ a number of virtually flavourless ingredients tofu, burdock and something called

Next page