Contents

About the Book

In this often hilarious yet deeply researched book, food and travel writer Michael Booth and his family embark on an epic journey the length of Japan to explore its dazzling food culture. They find a country much altered since their previous visit ten years earlier (which resulted in the award-winning international bestseller Sushi and Beyond).

Over the last decade the countrys restaurants have won a record number of Michelin stars and its cuisine was awarded United Nations heritage status. The worlds top chefs now flock to learn more about the extraordinary dedication of Japans food artisans, while the countrys fast foods ramen, sushi and yakitori have conquered the world. As well as the plaudits, Japan is also facing enormous challenges. Ironically, as Booth discovers, the future of Japans culinary heritage is under threat.

Often venturing far off the beaten track, the author and his family discover intriguing future food trends and meet a fascinating cast of food heroes, from a couple lavishing love on rotten fish, to a chef who literally sacrificed a limb in pursuit of the ultimate bowl of ramen, and a farmer who has dedicated his life to growing the finest rice in the world in the shadow of Fukushima. They dine in the greatest restaurant in the world, meet the world champion of cakes, and encounter wild bears. Booth is invited to judge the world sushi championship, enjoys the most popular Japanese dish you have never heard of aboard a naval destroyer, and unearths the unlikely story of the Englishwoman who helped save the seaweed industry.

Sushi and Beyond was also a bestseller in Japanese where its success has had improbable consequences for Booth and his family. They now star in their own popular cartoon series produced by national broadcaster NHK.

About the Author

Michael Booth is the author of five books, including the international bestseller, The Almost Nearly Perfect People, winner of the British Guild of Travel Writers award for Book of the Year, and Sushi and Beyond, which won the Guild of Food Writers award.

Also by Michael Booth

Just As Well Im Leaving

Doing without Delia

Sushi and Beyond

Eat, Pray, Eat

The Almost Nearly Perfect People

To my family

The whole of Japan is a pure invention . There is no such country, there are no such people.

Oscar Wilde

Chapter 1

The Return

A decade ago, in the autumn of 2007, I boarded a plane with my wife and our two sons and flew to Tokyo.

We were living in Paris where I had spent twelve months learning the techniques of classical French cooking at the Cordon Bleu school and then working in Michelin-starred restaurants in the city. I had wanted to learn how to cook without recipes, without the guidance of Jamie, Delia or Nigella, and I did, but along the way I had consumed about as much butter, cream, sugar and pastry as any mans elasticated waistband could accommodate. I was, if not jaded by dishes like blanquette de veau and livre la royale, then definitely feeling the effects of the calorific overload brought on by an excess of classical French cooking. My stomach was now entering rooms before the rest of me. Bits kept moving after others had stopped.

By way of an antidote, a friend had given me a copy of Shizuo Tsujis Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, back then one of the few books on traditional Japanese cooking available in English. Its recipes seasonal, light, healthy, modern and, as the title promised, simple were a revelation.

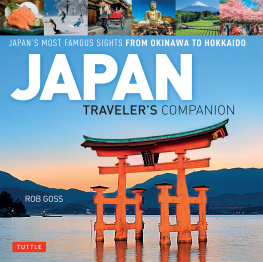

Inspired to find out more about what the Japanese ate and how they prepared it, I had booked four open tickets to Tokyo. My family and I ended up spending just over three months travelling the length of the country from Hokkaido in the chilly north to subtropical Okinawa in the south, exploring the dazzling diversity of Japans food culture, dining with sumo wrestlers, meeting Japans most famous food TV stars and discovering the secrets of how the centenarians of Okinawa lived well into three digits, among other adventures.

I wrote a book about our journey, Sushi and Beyond, but, rather than getting Japan out of my system, the whole experience only made me more eager to return. A new world had opened up of unfamiliar ingredients and strange techniques, a world which was utterly alien, often tantalisingly inaccessible, yet never less than beguiling. From the edible aquarium that was Tsukiji fish market, to Tokyos smoky yakitori alleyways, I was captivated. From the minimalist kaiseki restaurants where I held my breath between courses for fear of disrupting the flower arrangements, to the ascetic temple food of Mount Koya, I was perplexed yet fascinated.

I knew that on that first visit we had only really scratched the surface of Japans extraordinarily refined culinary landscape. We had visited fewer than a dozen of its forty-seven prefectures; so much about the Japanese what they ate, and why remained a mystery. That chronic sense of missing out had barely diminished over the years despite several return visits on my part to write food and travel stories for newspapers and magazines.

In the decade since our first visit to Japan there had been several major developments on the countrys food scene. There were headlines around the world when, in 2007, the first Michelin guide to Tokyo awarded more of its precious stars to the Japanese capital than to Paris. Whatever ones views of the value of Michelin, it seemed that Tokyo was now the worlds food capital, and subsequent guides, not just to the capital but to other Japanese cities, have reinforced the countrys status as the most starry in the culinary firmament. Then, in 2013, UNESCO granted Japanese cuisine Intangible Cultural Heritage status. This also made headlines globally and, although I suspect it meant more to the Japanese than it did to the rest of the world, as a result still more foreign chefs have visited Japan in the years since and been inspired by Japanese techniques, ingredients and presentation styles. Japan is, for instance, the source of all the snazzy open-kitchen counter restaurants and fixed multi-course menus which have come to define high-end dining in London, New York, Paris, Copenhagen and elsewhere; and the Japanese were doing the local/seasonal thing long before anyone else. Meanwhile, the fooderati bloggers, social media and conventional food media had gone crazy for ramen, and were slowly discovering other Japanese fast foods and ingredients. Had this given the Japanese a new pride in their so-called B-kyu gurume (B-class gourmet) foods about which Tsuji and Japans food elite had always tended to be rather sniffy? At least the Japanese had finally woken up to the branding potential of their food culture in terms of tourism and, as a result, there had been a record growth in foreign visitors in recent years, many of whom I suspect came primarily for its food. The tourist boom is likely to continue with the Olympics, awarded to Tokyo for 2020. How had the Japanese reacted to all this attention? How were its restaurants preparing to welcome the world, I wondered.

On 11 March 2011 an earthquake measuring 9.0 on the Richter scale struck just off the Pacific coast of eastern Japan, destroying entire towns and killing over 18,000 people. It was the most powerful earthquake ever to hit Japan and I suspect many around the world shared my horror as they watched the footage of the destruction of an entire region of the country. Since then, we have also witnessed the stoic resilience of the Japanese people in recovering from 3/11 but, among other things, the earthquake, tsunami and ensuing nuclear disaster devastated what had been an important food-producing region of Japan. What have been the long-term effects of the disaster?