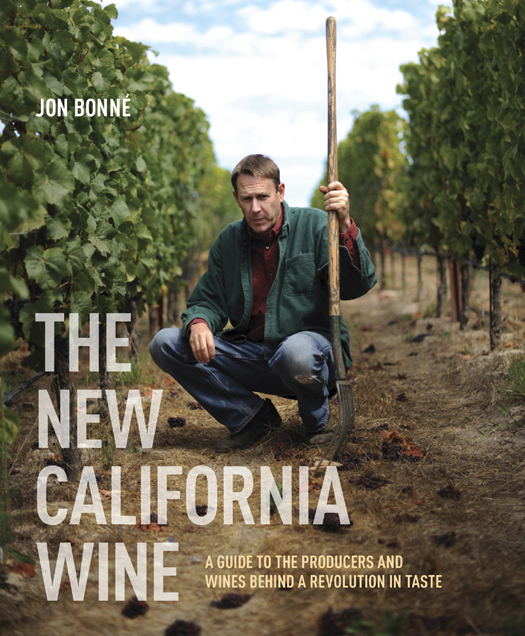

Copyright 2013 by Jon Bonn

Photographs copyright 2013 by Erik Castro

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Some material in this work includes quotes from or is based on pieces by Jon Bonn originally published in the San Francisco Chronicle . Grateful acknowledgement is made for the use of this material, as well as additional material from pieces originally published in Decanter and Saveur magazines.

The photos appear courtesy of Ted Lemon

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bonn, Jon.

The new California wine : a guide to the producers and wines behind a revolution in taste / Jon Bonn.

pages cm

1. Wine and wine makingCaliforniaGuidebooks. I. Title.

TP557.B64 2013

641.22dc23

2013017577

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-60774-300-2

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-301-9

Cartography by Moon Street Cartography, Durango, Colorado

v3.1_r1

The people who are experimenting are not generally found among the large growers, but are more likely discovered among the hills and retired nooks in the counties nearest the bay. I find that they have worked cautiously. Most of them are men of small property and limited means, and do the greater part of the work themselves. I think that the finest wines of the State will eventually be found to have been made by this class of viticulturists. They have time and they use it properly; they have ambition and they follow it. They do not reckon their time at so many dollars an hour. Very likely it will require some length of time before their products are appreciated, but the time will come either in their lives or in those of their children following. I know several people, the exact counterpart of those above described, and believe them the forerunners of a new era of wine making in our State.

Arpad Haraszthy, 1891

Contents

Introduction

I hear you hate California wine.

The spokeswoman for one of the states most powerful wine personalities was on the phone. I wasnt in the mood.

If I hated California wine, I replied, would I be doing what I do?

I knew, when I moved to California in 2006, that I was facing long odds. I had come to a place that believed, above all, in the superiority of its wines. Anyone who didnt embrace that belief was viewed as a threat. And in the past I had dared to voice my dissatisfaction with a California wine culture that I saw as often self-satisfied and underwhelming. Worse, I was from the East Coast, an outsider. My years spent in New York, where I learned from my father about European wines from Vouvray to Valpolicella, were a liability instead of an asset.

Six years earlier I had moved to Seattle, and while there I came to love West Coast winesin particular the pioneering wines of Washington State. I began my wine-writing career there. Clearly, I was no foe of American winemaking. But none of that mattered the moment I landed at the Oakland airport.

I had come to the Bay Area to run the wine section of the San Francisco Chronicle , six to ten pages of some of the countrys most influential wine journalism. The California wine industry was not pleased: their work was about to be judged by someone whose palate was honed not on hefty Cabernet and Zinfandel but on nuanced Old World wines.

I approached my work earnestly. But from the moment I arrived, I had to confront my own deep skepticism about Californias winemaking reality. Again and again I was disappointed by what I found to be the shortfalls of California wine: a ubiquity of oaky, uninspired bottles and a presumption that bigger was indeed better.

The truth was, I had come to California to be convinced. I was looking for signs that skeptics like me were wrong, and that what had long been a near-magical land for wine could still achieve greatness.

Whatever I might have thought about California wines at that point, I had started from a place of love. In February 1985, when I was twelve, my father took our family to California. At the time I was far more interested in the Apple factory tour in Cupertino, but Dad had always brought us up around wine. He gave me my first glass at age five, and soon enough I was having a bit with dinner most nights. When he took us to Napa Valley, it was clear we were somewhere special. We visited the Robert Mondavi Winery, with its campanile and familiar arch, the brick-and-mortar icon from the labels I had often seen around the house. Even then I knew we had arrived at the cradle of American wine. California wines at the time were vibrant, the industry invigorated by its speedy rise to rival Europe in quality.

Why, then, had California wine fallen into such a stupor years later? That was the question I set out to answer. I wanted to reconcile these two Californiasthe one I remembered that was so full of promise and life, and the one that was stuck in a self-satisfied funk.

My first couple of years in California were tough. I hunted desperately for local wines worth praising while I featured lots of imports in the newspapers wine section, arguing that the Bay Area in fact had a critical mass of great importers (like Berkeleys Kermit Lynch). This argument did not sit well among partisans of Californias wines, but I couldnt overlook the sad fact that Napa had become a bombastic shell of its earlier, humbler self. Its top namesBeaulieu and Beringer and even Mondavihad grown into big corporate entities, while its smaller labels were locked in an arms race, each trying to create bigger, riper, and more outrageous wines.

Still, I had come prepared with good leads. Just two weeks into the job I had to choose our winemaker of the year, and quickly enough I selected Paul Draper of Ridge Vineyards. Drapers work was beyond reproach: for nearly forty years he had been at the helm at Ridge, where he made not only the states benchmark Zinfandel-focused wines, Geyserville and Lytton Springs, but also one of the finest Cabernet-based wines in the world, Monte Bello.

My choice of Draper came with a subtler message. In the midst of an industry that had blindly embraced technology and by-the-numbers winemaking, he was an outspoken traditionalist. He rejected commercial yeasts and fancy flavor-enhancing techniques and was a vocal critic of the science-minded efforts of the University of California at Davis, one of the top winemaking schools in the world.

![Jon Bonné - The New French Wine [Two-Book Boxed Set]: Redefining the Worlds Greatest Wine Culture](/uploads/posts/book/443558/thumbs/jon-bonn-the-new-french-wine-two-book-boxed.jpg)