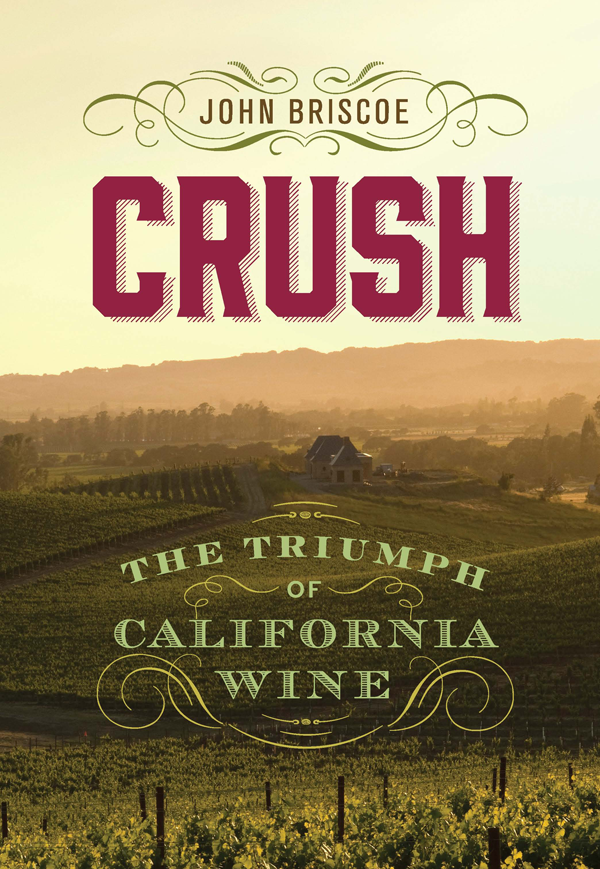

Title: Crush : the triumph of California wine / by John Briscoe.

Description: Reno : University of Nevada Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 978-1-943859-49-8 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-0-87417-715-2 (e-book) | LCCN 2017036463 (print) | LCCN 2017037617 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Wine and wine makingCaliforniaHistory. | WineriesCaliforniaHistory. | VineyardsCaliforniaHistory. | ViticultureCaliforniaHistory.

Classification: LCC TP557.5.C2 B75 2017 (print) | LCC TP557.5.C2 (e-book) | DDC 663/.209794dc23

I was interested in California wine. Indeed, I am interested in all wines, and have been all my life, from the raisin wine that a schoolfellow kept secreted in his play-box up to my last discovery, those notable Valtellines, that once shone upon the board of Caesar.

The stirring sunlight, and the growing vines, and the vats and bottles in the cavern, made a pleasant music for the mind.

Preface

Love of good living is one of the peculiarities of the nation, possibly, but in California the national weakness is a ruling passion.

NOAH BROOKS, Restaurant Life in San Francisco, Overland Monthly

CALIFORNIANS TALK WINE more than they do weather; but, unlike weather, they actually do something about wine. They swirl it, peer at and through it, inhale it, sip it, and guzzle it. They also make itin both small and prodigious quantities, and in qualities ranging from nearly swill to rather swell.

And they write about it. Californians, native or adopted, have been writing about wine for as long as theyve been making it. Father (now Saint) Junpero Serra, the Spanish founder of the California mission system, bemoaned in his letters the short supply of wine. The putative father of California wine, Agoston Haraszthy, wrote scientific treatises on it in the mid-nineteenth century, both for the California legislature and for readers in general; he was followed by more historicalor, at least, anecdotalwriters like Frona Eunice Wait. Writing about California wine then proliferated in the twentieth century. Some discussed just one varietyZinfandel, for example; others described a particular growing region, like Napa Valley. Still others addressed only a particular terroirthe particular blend of soil, climate, and sunlight that make any grape its ownwithin a region. Some are serious, scholarly works; some, though no less serious, are intended for the nonacademic reader; and some, notwithstanding the very self-serious nature of wine and winemaking in California, are light, effervescenteven gossipy.

So why another book about California wineor, more precisely, why this particular addition to the prolific and proliferating literature on the subject? For one, the history of wine and wine-making in California is entwined with the tumultuous boom-and-bust history of this stateeven, dare I say, with the history of the world. Yet the many excellent books on wine and its historyin California do not sufficiently reference or illuminate the larger history in which took place, for example, the fiasco of 1915namely the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Indeed, this leads to the second point: the 1915 debacle was just one of several crushing setbacks to the wine industry, and yet most histories recognize just the disaster brought on by Prohibition. And third, while several of the books have a richness, even a surfeit of details, none teases out the most pertinent strands of Californias wine historynotable for five high points and four devastating low ones. One history of winemaking in California (assiduously researched, maddeningly unfootnoted) doesnt even mention a significant pinnacle of California winemaking, a blind tasting in Paris in 1976even though the event occurred a mere seven years before that books publication.

A fourth reason is particularly impressive. San Franciscos culinary traditionand, by extension, Californiasbegan in the Gold Rush of 1849, from which it catapulted to ambrosial heights. No city on earth, that we know of, had attained such greatness in any endeavorbe that food, wine, art, or military conquestin such short order.

The wine tradition of California began as early as 1769. But it would take more than two hundred years before any authority would rank California wines as having achieved world-class statusand even then the winners would likely not have been selected had they been identified as Californian.

In the end, there are many stories of wine and California. This particular one suggested itselfwith an insistent, almost audible ahemas being worthy of writing.

Notes

. Serra, Writings of Junpero Serra, 1:263, 281.

Introduction

Providence has given us the most extended wine country in the world, as if to complete our means of industry, wealth, and human happiness; and who so insensate as to place obstacles in its development?

MATTHEW KELLER, California Wines

WHEN OUR FOREBEARS first made wine, how they did it, and how their first vintage tasted, well never know. We do know there were wine jars in the tomb of Scorpion I of Egypt, dating from 3150 BCE. Scorpions wines came not from Egypt, scholars believe, but from the Jordan River valley.

We also know that the kings and soldiers of the Trojan War drank wine. In the Iliad and Odyssey Homer refers scores of times to a wine-dark seanotwithstanding that no vintage has the color of the Aegean. When Achilles insults Agamemnon he calls him a wine sackor, in more modern translations, a staggering drunk.

Wine figures throughout the Old Testament. After the Flood, Noah apparently planted a vineyard, made wine, got drunk, fell asleep naked, and raged livid at his son for finding him so.

Alexander the Great liked wine so much he had his own wine-pourer, a young man named Iollas. Indeed, wine may have been Alexanders undoing. Some historians state he died of alcoholism; others suspect that Iollas poisoned Alexanders wine at the behest of Iollass father, Antipater, who had fallen out of favor with Alexander (and whose name sounds suspiciously seditious, like anti-father).

A few centuries after Alexander, wine served as the dramatic tension for the New Testament story of the wedding feast at Cana. When the wine ran out, Jesus changed water into wineand good wine at that. Of course, wine was poured at the Last Supper as well.

In the common era, winemaking was, interestingly, imported to France twice. First came the Phoenicians, who settled Marseilles in 600 BCE. As Andr L. Simon notes in his book The Noble Grapes and the Great Wines of France, the Phoenicians had no need to bring cuttings of their own Eastern vines: they had only to prune, train, and tend the [wild] native vines in order to get better grapes and to make wine. Five hundred years later, when Julius Caesar came to, saw, and conquered Gaul, he bid the lands nearest essential waterways be stripped of their trees so as to prevent unexpected assault by hidden, resentful natives. Caesar then encouraged pliant residents to plant vineyards in the river valleys of the Loire, Marne, Rhne, Sane, and Seine. But he didnt do this just to produce wine; by this means he also sought to more deeply root the locals to their soilas well as to him. When Crassus extended Roman dominion to the Atlantic a few years afterward, he found a flourishing viticulture already rooted in the area we know as Bordeaux.