Contents

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

First published in the United States by Hudson Street Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company in 2014

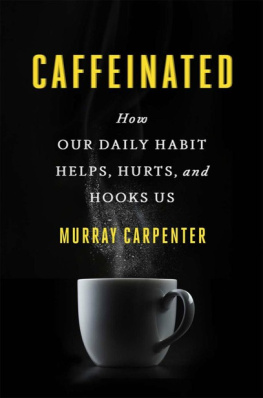

Copyright Murray Carpenter 2014

Murray Carpenter asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover photograph Shutterstock.com

Source ISBN: 9780007558513

Ebook Edition March 2014 ISBN: 9780007558520

Version: 2014-03-06

Introduction:

A Bitter White Powder

Propped up on my desk before me, there is a vacuum-sealed Ziploc bag of white powder. About the size of a compact disc, the package weighs one hundred grams. The powder is an alkaloid, extracted from the leaves and seeds of plants that grow at mid-elevations in low latitudes.

Chemists would recognize this substance as a methylated xanthine, composed of tiny crystalline structures. Biologically, the molecule is so useful that it emerged independently on four continents as an insecticide, keeping pests from nibbling on its host plants.

Lets get personal this substance courses through my veins as I write these words. It is a drug, and I have been under its influence nearly every day for the past twenty-five years. And I am in good company. Most Westerners take this drug daily. It is so effective, yet so simple, that if it did not grow on trees a neurochemist would have invented it.

This is, of course, caffeine, a bitter white powder. It is the essence of coffee or tea and the key ingredient in soft drinks, energy drinks, and energy shots. In moderation, caffeine is best known for something it does simply and effectively: It makes us feel good. But it is a drug whose strength is consistently underestimated. A sixty-fourth of a teaspoon, the amount in many soft drinks, will give you a subtle boost. A sixteenth of a teaspoon, about the amount in 350ml of coffee, is a good solid dose for a habituated user. A quarter teaspoon will lead to bodily unpleasantness racing heart, sweating and acute anxiety. A tablespoon will kill you.

Three years ago, when I decided to follow caffeine where it led me, I thought the drug was fantastic. Not only was it the easiest, cheapest way to rev up my day, increase my concentration and boost my productivity; I felt sure that it must not be really bad for you (if it were, science would have revealed it by now) and that the industry must be pretty big. But as the story took me to the coffee farms of central Guatemala, the worlds largest synthetic caffeine factory in China, an energy shot bottler in New Jersey, and beyond, I learned that I had underestimated caffeine on all accounts.

I had underestimated the drugs effects on our bodies and brains. I had underestimated the scope and scale of the caffeine industry. And I had underestimated the challenges regulators face in trying to rein in an industry running wild.

Caffeine sharpens the mind, especially for people who are stressed, tired, or sick, whether they use it regularly or not. It was a neuroenhancer long before the term came into vogue. It does not just increase acuity; it can also improve mood. A review of the psychological effects of caffeine puts it this way: of caffeine are reliably associated with positive subjective effects. The subjects report that they feel energetic, imaginative, efficient, self-confident, and alert; they feel able to concentrate, and are able to work but also have the desire to socialize.

Athletes using caffeine are stronger and faster than their drug-free peers. It has even helped Navy SEAL recruits perform better during the tryouts known as Hell Week, perhaps the most diabolical, arduous test of mental and physical fortitude ever devised. And its an effective treatment for hangovers.

Caffeine can make you stronger, faster smarter, and more alert, but it is not quite the perfect drug. In some people, it can trigger severe and unpleasant psychological effects, such as acute anxiety and even panic attacks. These are most pronounced in people with genetic variants that make them more susceptible to caffeine. Any caffeine user who believes its totally benign should try going without it for a few days. Caffeine withdrawal is real and unpleasant, often including headaches, muscle pain, weariness, apathy and depression. On a subtler level, many Americans fall into a routine of diminished sleep followed by large doses of caffeine a vicious circle.

Caffeine is not as powerful as cocaine, which can be deadly at just over a gram in inexperienced users. Youd need to down about fifty cups of coffee at once, or two hundred cups of tea, to approach a lethal level of caffeination. But if you go straight for the powder, you can get a lot in a hurry. On 9th April 2010, near his home in England. He ate two spoonfuls of caffeine powder hed bought online, washing them down with an energy drink. He soon began slurring his words, then vomited, collapsed and died. Bedford likely ingested more than five grams of caffeine. The coroner cited caffeines cardiotoxic effects as the cause of death.

The caffeine conundrum is this: It can be a fantastic drug one of the very best but, like any powerful drug, it can cause problems with real consequences.

So, its safe to say that I had definitely underestimated the drugs psychomotor effects. But to a greater degree, I had underestimated the scope and scale of the caffeine industry. I learned that the addictive, largely unregulated drug is everywhere in places youd expect it (like coffee, energy drinks, teas, colas and chocolate) and in places you wouldnt (like orange sodas, vitamin tablets and pain relievers).

I learned that brands such as Coca-Cola have ducked regulatory efforts for decades, even as they quietly use the drug to reinforce our buying patterns. I learned that consumers are uninformed about caffeine because Coca-Cola, Monster, 5-hour Energy and even Starbucks persistently and systematically downplay the drugs importance.

We need to look no further than the items on my shelf to get a sense of the breadth of the industry: Amp energy gum and 6 Hour Power energy shots both energy drinks and Jitterbeans a highly caffeinated sweet (chocolate-covered espresso beans). Cans of Red Bull, Rockstar 2X Energy and Mega Monster energy drinks. There are bottles of Mountain Dew and Coke, and the cans of Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi that I used to methodically wean myself from caffeine for the first time in decades. There is a small package of roasted and ground cacao, which I purchased in Chiapas, where it is grown. Ive got a bottle of Lipton iced tea and a couple of bags of Morning Thunder, a combination of black tea and yerba mat (an evergreen South American plant with caffeinated leaves). Ive got a box of black tea packaged by a one-man gourmet tea shop in the Green Mountains of Vermont and a single-serving K-Cup full of coffee that was processed in the massive factory a half mile away. Theres a canned coffee drink of the sort that is wildly popular in Japan and several packs of military-strength chewing gum that I picked up at an army research lab. There is a package of Starbucks instant coffee labeled in Mandarin and several ounces of Iron Buddha loose-leaf tea I bought at the worlds largest tea market in Beijing. In Ziploc bags, Ive got raw kola nuts the sort that African men chew for a caffeine boost and guarana berries, from the South American vine that packs more caffeine per ounce than any other plant. There are caffeinated energy gels, too, made for athletes: Clif Shot Bloks and a foil package of Gu that I picked up at the Ironman World Championship in Hawaii.