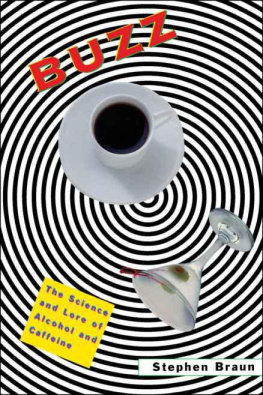

Buzz

Buzz

THE SCIENCE AND LORE

OF ALCOHOL AND CAFFEINE

Stephen Braun

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogot Bombay

Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi

Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Copyright 1996 by Stephen Braun.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press,

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Braun, Stephen.

Buzz : the science and lore of alcohol and caffeine /

by Stephen Braun,

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-19-509289-9

1. AlcoholPopular works. 2. Caffeine--Popular works.

I. Title.

QP80LAW3 1996

61 $.7828dc20 95-47790

The author and publisher thank the following for permission to reprint specified material:

From One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish by Dr. Seuss. TM and copyright 1960 and renewed 1988 by Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P, Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

Excerpted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, from A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway. Copyright 1964 by Mary Hemingway. Copyright renewed 1992 by John II. Hemingway, Patrick Hemingway, and Gregory Hemingway.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid free paper

To the memory of

Robert Arnold Braun

Shaman, Scientist, Father

Acknowledgments

The idea for this book germinated during a fellowship in neurobiology at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. There I was introduced to a radical new understanding of the brain and the way it worksand there, too, I saw clearly for the first time how substances such as alcohol and caffeine could affect the machinery of the mind. I am indebted to Irwin Levitan, the scientist in charge of the lab in which I was a student, for his patient explanations, steadfast encouragement, and infectious enthusiasm for neuroscience. To the MBL I owe thanks as well, for offering science journalists such a unique opportunity to experience science by doing it, rather than simply reporting it.

Buzz has benefited tremendously from the keen-eyed review of many scientists. Foremost among them is Steven N. Treistman, who carefully and thoughtfully read the entire manuscript and who was an unflagging supporter of the project from day one. In addition, the following scientists took time from busy schedules to read selected chapters or chapter portions: Gary Kaplan, Thomas Dunwiddie, Barry Green, Robert Greene, and Annette Rossingnol. Other scientists helped by answering often lengthy lists of questions and by providing copies of papers on relevant subjects. My thanks to Robert D. Blitzer, Joseph Brand, James Brundage, Michael Charness, John Daly, David Lovinger, Quentin Regestein, Forrest Weight, and Mark Whitehead.

For the excellent molecular models included in the book, I thank Joe Gambino of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. The superb line drawings of ion channels and the neuronal synapse are the work of Ann Bliss Pilcher.

I am grateful to Howie Frazin and Lynn Prowitt for deftly finding the confusing parts and helping me clarify them. My editor at Oxford University Press, Kirk Jensen, provided invaluable guidance and repeatedly led me to the correct voice for the book. I am also most grateful to copy editor Gail Weiss, whose many valuable suggestions improved Buzz considerably.

Finally, my heartfelt thanks to Mary Anna Towler for teaching me to write; to Steve Pilcher, Tim Braun, and Doug Beyers for invaluable lessons in perceptual relativity; to Oralec Stiles for the fabulous quote; and, above all, to my wife, Susan Redditt, for patience far beyond the call of duty. Were it not for her loving support in matters great and small, this book would not have been possible.

Contents

Buzz

Introduction

The government of a nation is often decided over a cup of coffee, or the fate of empires changed by an extra bottle of Johannisberg.

Duc de Richelieu

Aristotle, in The Problemata, posed the following questions: Why are the drunken more easily moved to tears? Why is it that to those who are very drunk everything seems to revolve in a circle? Why is it that those who are drunk are incapable of having sexual intercourse? Aristotle considered the brain nothing more than a radiator for cooling blood, so its not surpising that he couldnt answer these questions. He and others attributed the intoxicating powers of wine and beer to mysterious spirits of inebriation.

In a similar vein, seventeenth-century doctors puzzled over the stimulating effects of coffee and tea. Some argued that the beverages contained cold and moist essences that altered the balance of the bodys four vital fluids, or humors. Others, however, thought that coffee and tea should be classified as warm and dry in the humoral spectrum. The issue was never resolved, though it exercised some of the eras best medical minds for decades.

Alcohol and caffeiene today are the worlds most widely consumed mind altering substances, and people are as curious as ever about what they are and how they work. Like Aristotle, they wonder why, when theyre drunk, they see things spinning and why alcohol can deaden sexual response. In addition, people have new questions, arising as often from media reports of scientific studies as from popular myth. Do women become intoxicated more easily than men? Does caffeine worsen premenstrual symptoms? Is alcoholism a genetic disease? Is caffeine bad for you or isnt it? Does alcohol really kill brain cells? Can caffeine help you lose weight?

The answers to such questions elude even sophisticated consumersthose who know their cabernet sauvignon from their sauvignon blanc, and their Kenya AA from their Aged Sumatra. The reason is simple: until very recently, nobody has been able to answer these questions. Its not that alcohol and caffeine are terribly complex or difficult to understand. In fact, they are rather simple molecules, the structure of which has long been known. The problem is that the target of those molecules, the human brain, is terribly complex and difficult to understand. Progress in learning how alcohol and caffeine work has had to wait for new knowledge of how the brain works.

Fortunately, in the past two decades the science of the brainneurosciencehas blossomed. New investigative techniques have opened up the black box of the brain and have begun to shed light on its inner workings. Out of this new insight has come a radically improved understanding of how alcohol and caffeine work. Much of this information is so new that it is known only to certain research scientists and people who read scientific journals. And on the rare occasion that new findings have made it from the lab bench to the corner bar, the message often arrives garbled.

Next page