CONTENTS

Mind you, a lot can happen in a week. It just did.

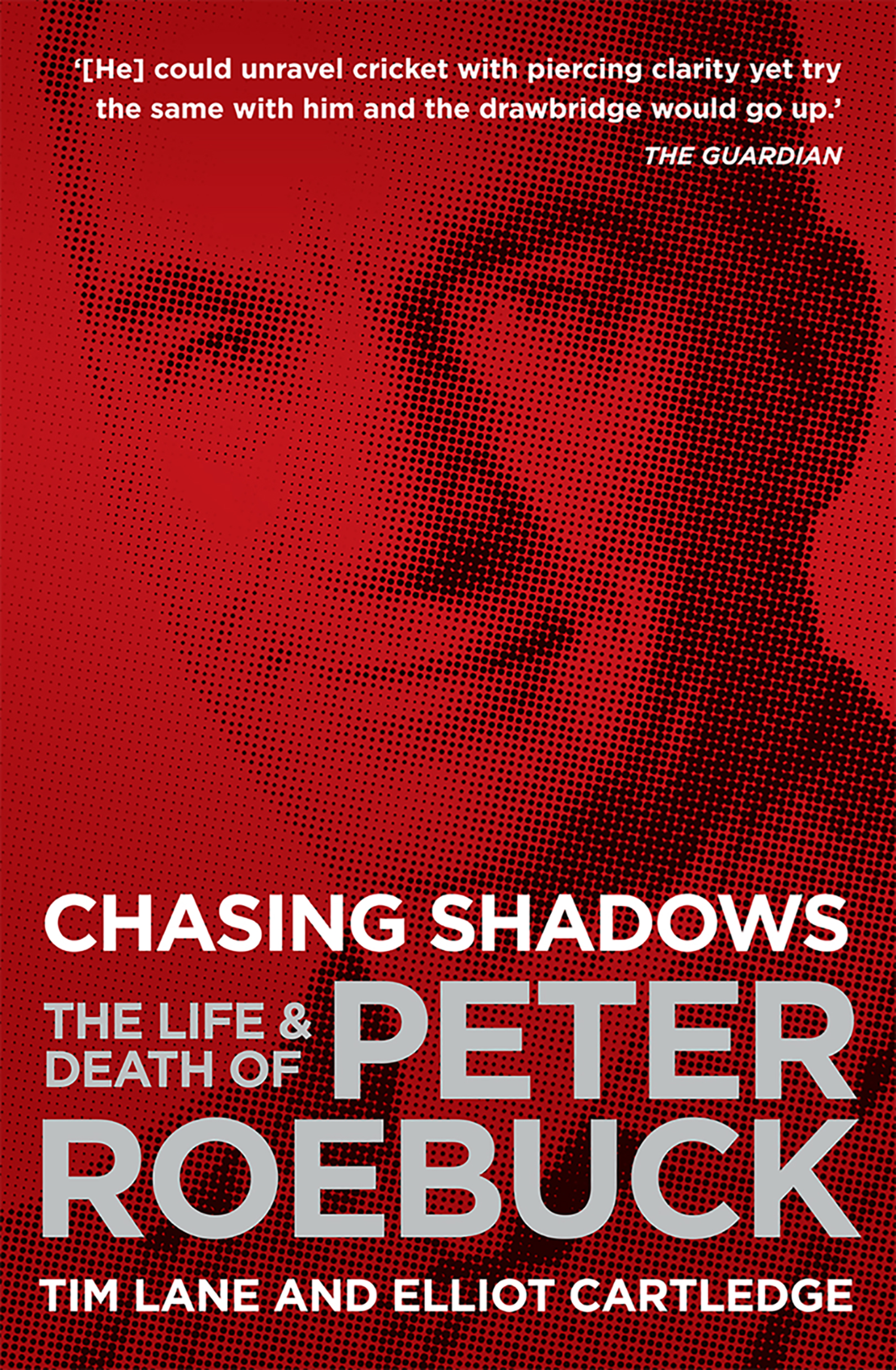

Peter Roebucks final column, 13 November 2011

Friday, 11 November 2011

Newlands, Cape Town

At one of the worlds most picturesque sporting grounds a strange cricket match has been unfolding. Twenty-three wickets fell on day two, a Thursday. Fans back home in Australia, waking up to the score, thought they had missed a day. First South Africa crumbled for 96, to trail by 188 runs on first innings. Then Australia were reduced to a calamitous 9 for 21, on their way to an eventual 47, Vernon Philander on debut displaying a nerveless mastery of conditions to claim 5 cheap wickets. The turnaround was stunning. By 11.11 next morning, on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 2011, South Africa required 111 to win. They got them by lunchtime, captain Graeme Smith bringing up his own hundred one over and the winning run, a clip through midwicket, an over later. Cock-a-hoop twenty-four hours earlier, the Australians were in a state of disbelief. No Test cricket on the weekend for the Capetonians, tweeted former South African fast bowler Shaun Pollock, they will have to head for the beach!

Tickets for Saturday and Sunday, the scheduled days four and five, had been selling well, making the premature end a disaster for vendors, caterers and the grounds custodian, the Western Province Cricket Association. For the travelling media, however, it was a rare opportunity for free time on a weekend. Members of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation commentary team were staying at the nearby Southern Sun Hotel. Somewhat unusually, Peter Roebuck was with them. Well known for his eccentrically private ways, Roebuck had been inclined over the years to stay at lesser establishments of his own choosing. As his Fairfax newspaper colleague Greg Baum puts it, Even in more lavish times for Fairfax, when we were nearly always staying in the team hotel, he would stay in a two-star hotel somewhere else and eat at a ten-dollar diner around the corner.

Inside that cheap diner, Roebuck would most likely be found with his nose buried in a book. How he found time to refresh his knowledge stores with new material and to be abreast of so much was a constant source of mystery to his various friends and admirers in the media; the fact that he generally steered clear of the after-hours pockets of journalists as they dined and wined was no doubt part of his secret.

Years earlier, in Peshawar, where Mark Taylor was busy making a triple century, all but one of the ABC team were staying in and enjoying the relative opulence of the Pearl Continental. Roebuck joked daily that he was lodging at a place called Greens. The establishment is still operating today, a decidedly no-frills option. That was more Roebucks style.

Unusually for one whose spirits vacillated, he had appeared in fine fettle this whole Cape Town Test. Baum arrived at the ground early on Friday. He noticed Roebuck discussing player matters with Tony Irish, CEO of the South African Players Association. Allan Border was there and Roebuck talked to him too. It did strike me at the time, says Baum, that he was particularly jovial. He could be excessively that, and then excessively morose too, but it did seem like he was in a good place.

Much of the press pack was in a similar good place. It is an ongoing sore point for newspaper reporters, as opposed to those who inhabit the supposedly cushy TV and radio boxes, that when the match is over their work goes on, sometimes increasing in volume and intensity. Roebuck worked on both sides. A weekend of no cricket in one of the worlds more scenic cities was a rare luxury. Some put their feet up and thought about the next match. Or golf. There were wineries, restaurants, beaches, trips to Robben Island and the top of Table Mountain to consider.

Friends were contacted, bookings made, plans set.

Saturday, 12 November 2011

Southern Sun Hotel

Given his penchant for less sophisticated digs, it was rare for this elusive pimpernel of a colleague to be just down the hallway, and equally unusual for him to be sharing breakfast with them. Roebuck was as happy as some had ever seen him. Part of the reason for his contentment at breakfast that Saturday was tangible, for he wasnt unaccompanied. Sitting at a table adjacent to fellow ABC commentator Drew Morphett, he introduced his companion with obvious pride. Im really excited, he told Morphett. Id like to introduce you to my future daughter-in-law.

The woman was to marry one of the young Zimbabwean men who lived at Roebucks home in Pietermaritzburg, on the other side of the country, and studied at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He regarded the members of this community as his adopted sons and they referred to him as Dad.

Another ABC commentator, former fast bowler Geoff Lawson, also recalls Roebucks demeanour that morning as unusually buoyant as effusive and alive and aware as youve ever seen him. One of us said, Youre in a good mood today, and he said, Im going to see my boys. Its Saturday and I get to see them play cricket. While the cricket he planned to watch would not be Test cricket, and the ground on which it was to be played was not a Test ground, its likely the occasion meant more to Roebuck than the match he had sat witness to the previous three days. He told Morphett and Lawson he was heading to Basil DOliveira Oval and Basils grandson would be playing.

The name Basil DOliveira is inextricably bound to the struggle of cricket and sport on its way to multiracial equality in South Africa. Born in Cape Town of Indian and Portuguese descent, and thus classed under South African law as coloured, DOliveira was an all-round cricketer of rich and obvious talent who had no hope of representing his country so long as apartheid flourished. In 1960, aged twenty-eight, he emigrated to England to further his career, and by scoring 158 in the Oval Test of 1968 he played what venerated sportswriter Ian Wooldridge described as probably the most significant modern Test innings.

His form commanded selection for Englands forthcoming tour to South Africa. DOliveira was overlooked. It was patently obvious why. He was coloured, and his selection would have triggered the tours cancellation; South Africas prime minister, B.J. Vorster, had stated DOliveiras inclusion would not be acceptable to the ruling regime. But his omission caused uproar in England. When seam bowler Tom Cartwright was subsequently injured, DOliveira was his replacement to no avail, as despite eleventh-hour negotiations, the tour was scrapped. Already barred from the Olympics and international soccer, South Africas home series against Australia in 196970 would be their last exposure to sanctioned international cricket until the fall of apartheid.

Of all the issues on which Peter Roebuck would write over a thirty-year period, there was none he was more passionate about than race. He had staunchly opposed sporting links with South Africa during the boycott years, and when apartheid fell and South Africas cricket team returned to the stage, he declared that he regarded the nations previous history in the sport as null and void.

Roebucks views on race and racial discrimination extended well beyond southern Africa. To the consternation of certain media peers, he argued vehemently that crickets non-white nations were unjustly targeted in regard to suspect bowling actions. He was seen to back teams from the subcontinent on issues such as on-field behaviour. His dedication to the cause of racial equality obscured, in the opinion of some, his better judgement. Unquestionably, though, he put his money and his endeavour where his mouth was, his commitment to those disadvantaged by decades of disenfranchisement extending to the way he lived his life and where he lived it. Although a dual British and Australian citizen, he bought a house in Pietermaritzburg and there provided for the upkeep and education of a small community of young men, mostly plucked from St Josephs orphanage in Harare.