Copyright 2009 by Matt Christopher Royalties, Inc.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: December 2009

Matt Christopher is a registered trademark of Matt Christopher Royalties, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-09542-6

Most years, December is not an important month for Major League Baseball. The regular season is long over. The World Series has crowned its new champions. Spring training is weeks away.

But December 2007 was different. On Thursday the thirteenth, anyone remotely interested in baseball planned to be near a radio, television, or computer at two oclock. Thats when the findings of a two-year investigation of Major League Baseball were to be announced.

The investigation was aimed at discovering the truth behind rumors that certain professional players were using performance-enhancing drugs to improve their game. The use of such substances was banned by MLB; anyone discovered to be using them would undoubtedly find his reputation forever tarnished.

The investigation was ordered by MLB commissioner Bud Selig and conducted by former senator George Mitchell. Mitchell interviewed players, owners, trainers, and others suspected of using, distributing, or administering the drugs. Then he compiled his findings into a hefty 409-page document known as the Mitchell Report.

Long before the report was published, baseball followers had speculated that some players used the drugs. What they didnt know was who in particular was guilty. The Mitchell Report promised to give them the names of those players.

Throughout the morning of December 13, radio stations, television networks, and Internet sites buzzed with predictions of the names that would appear in the report. No one would know who was on the list for sure, however, until two oclock.

Or would they?

A few hours before the report was to be made public, the television station WNBC in New York City and its Web site, msnbc.com, posted a list of players whose names supposedly appeared in the Mitchell Report. The list was unconfirmed but that didnt stop some in the news media from reporting it as fact.

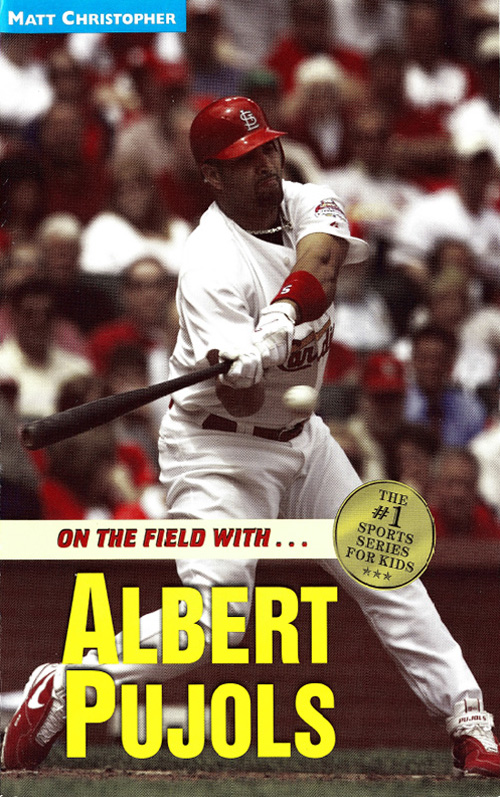

Sadly, many of those names didnt strike people as surprising. But for Missouri baseball fans, one name came as a shock: Albert Pujols, the 27-year-old first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Pujols had been a star slugger for the Cards ever since joining the team in 2001. He had the lean, muscular physique of someone who trained hard year-round. He worked long hours to improve his game; according to many, he spent as much time reviewing videotape of his swing as he did on perfecting its motion. He was also known for his strong religious convictions and his dedication to his family.

But was all that just a sham? Were his abilities really thanks to drugs, not hard work?

People wanting immediate answers to these and other questions would just have to wait. The official Mitchell Report and the truth about Albert Pujols wasnt due to come out until two oclock. Until then, they were left wondering and hoping that their loyalty to their favorite player would be rewarded in the end.

Jose Alberto Pujols, later known simply as Albert, was born on January 16, 1980, in Santo Domingo, capital city of the Dominican Republic. His father, Bienvenido, was a well-known and respected pitcher for one of the Dominicans baseball teams. Bienvenidos job required him to crisscross the small island country playing ball, which meant he could not care for his son himself.

Baby Albert was in good hands, however. His grandmother, America, raised him along with Bienvenidos eleven brothers and sisters. These children were Alberts aunts and uncles, but because of their close upbringing, they were more like his own siblings.

Santo Domingo, like many large cities, had its share of poverty and crime. The Pujols werent rich; indeed, by some standards, they were quite poor. But they made do with what they had and rarely experienced want of anything essential. America also made sure Albert and the other children understood the difference between right and wrong. Her strong religious beliefs helped her raise them to be good, moral people who understood that taking to a life of crime was not a solution to ones problems.

As Albert grew, he did what many young boys in the Dominican Republic did. He went to school. He did chores. He roughhoused and played with his friends.

I played video games when I was a little boy, but not that much, he once said in an interview. I was more interested in being outside, and playing baseball. I learned to play on the streets in the Dominican Republic when I was eight years old.

Albert wasnt the only young boy playing baseball. The Dominican Republic has a long and colorful baseball history. Researchers believe the game itself was first introduced to the island about a century and a half ago by people from Cuba, who themselves had learned it from Americans.

The game took root in the Republic almost immediately, thanks in large part to sugar plantation owners who encouraged their workers to play in the months after the harvest. They helped organize teams and create fields, paid for players to practice, and arranged games.

From the plantations, the sport spread throughout the country. By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, four official teams had been formed. That number grew with the sports popularity, not only in the Dominican Republic but in surrounding Caribbean nations, too. The 1920s and 1930s saw fierce competition among teams from these different countries.

Players from the United States, including members of the Negro League such as Satchel Paige, also participated in competition in the Dominican Republic. They soon realized how talented many players from the tropical islands were. When they returned home, they brought stories and information about these players with them.

Major League Baseball didnt hurry to recruit Dominicans, however. In those days, professional baseball players came in only one color: white. In fact, it was an unspoken rule among team owners that no player of African, Hispanic, or Asian descent was to be allowed on to play in the major leagues.

That all changed in 1947, when Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, offered Jackie Robinson a spot on his team. Robinsons admittance to the major leagues opened the door for other players of color. One of those players was Ozzie Virgil, who in 1956 became the first Dominican to play professional baseball in the United States.

He was not the last. In the decades that followed, many talented ballplayers from the Dominican Republic had successful careers in the major leagues. Theres pitcher Juan Marichal, who would later become the first Dominican elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Felipe, Jesus, and Matty Alou made history by becoming the first set of brothers to play together on the same team at the same time. And Manny Mota pinch-hit his way into the record books.