The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

When I was a boy, my father, during our weekly phone conversations, used to tell me stories about the mythical kingdom of Camelot. I am not certain how closely his versions adhered to the canonical legends, but I think he got the basics right: there was King Arthur, an orphaned peasant boy who pulled the magic sword, Excalibur, from a stone; there was the wizard Merlin, Arthurs adviser, and Guinevere, his beautiful queen. And then there were the Knights of the Round Tablea gang of impressive but indistinguishable men who, unhindered by domestic life, upheld the moral order of Camelot and protected it from evil. The most valiant of Arthurs knights, my father told me, was a mysterious figure called Lancelot. He came from nowhere, lived alone, and spent his days wandering the forest looking for someone to fight.

At the time, I was living with my mother and older sister in an unfinished apartment building in downtown Brunswick, Maine; my father lived five hours away, in an old farmhouse called the Birches, in the Champlain Islands of northern Vermont, with a white woman named Martha and her five children. I knew the Birches well: the property stood a few miles down the road from the house where I was born, the same house, just months ago, my mother had left behind to start a new life in Maine.

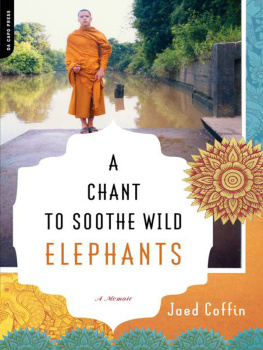

My mother had come to America from a small village in rural Thailandshed met my father, a soldier, on a military base during the Vietnam Warand every year, for about three weeks, she took us back to visit. I knew much less about where my father had come from; the Camelot stories were his way of acquainting me with his cultural origins, origins that, he said, came from a place called Great Britain.

To connect himself with this lost heritage of men, my father had begun taking riding lessons at a local stable. I liked the image of my father atop a horse. Though I knew that he was not a real knight, I understood that hed been a soldier of some kind, and the combination of horsemanship and war made me believe that my father belonged to a special class of men. During one of our phone conversations, my father told me hed recently been thrown by his horsean accident that, he said, could very well have killed him. As I pictured my father soaring through the air, I reminded myself that, despite his recent absence from my life, the sound of his voice was proof that he was alive. So the image of my father falling was replaced by a vision of him rising to his feet, adorned in a suit of armor.

When I told my mother about my fathers fallthinking that she would want to know that a man we both loved had survived a near-death experienceshe paused before responding. I was, by then, used to my mothers delayed comprehension. But the nature of my concern, that my fathera man who had left our family to live in the house of another woman and her five childrenhad been injured while galloping around a stable on a horse, would likely not have made sense to her even in Thai.

My mother dismissed my concerns with the same pragmatic indifference she employed in her work as a psychiatric nurse at the local hospital. Every night at ten oclock, she would leave our apartment for an eight-hour shift, only to return the next morning to relieve a babysitter and deliver my sister and me to school. She slept only two or three hours a day. My sister and I had invented a game called I need to sleep! in which one of us would lie in bed while the other person would tiptoe around it. Any noise and the sleeping mother would explode upright and scream, I need to sleep! and the game would be over.

Somehow I still believed that my mothers fatigue had something to do with a failure to adapt to our American life. Every time she took my sister and me back to Thailand, the twelve hours of time difference cast her past and present worlds in stark opposition. All night, my sister and I lay awake beneath the white drape of a mosquito net, telling each other jokes or listening to the sound of my grandfather snoring, waiting for the first call of a rooster, or the opening bars of the Thai national anthem erupting from public speakers, to signal the arrival of first light. During the day, we wandered around our familys villagea dusty collection of stilt houses gathered along a muddy canalpaying respects to slow-moving old people whose mouths dripped red with betel-nut juice. That these people were introduced to me as blood relations, and that they seemed to know me, expected something from my mother, and always asked after my father, only made the dream of my mothers past more impossible. Whenever we returned to Maine, I always felt less certain about my relationship to that place than when Id left.

By the time I was in second grade, my sister and I began to spend our summers at the Birches. I do not know what emotions my mother put aside before allowing her two children to be cared for by her former best friend; perhaps, finally able to get some sleep, she was glad to see us go. On the days my father arrived, my mother would take extra time to comb my hairLike a prince! she saidand dress me in a button-down flannel shirt with a clip-on necktie. But she often packed my bags full of soiled socks and underwear (a phrase that my sister and I always mimicked as sock and underwears), perhaps to remind my father and his new lover that our dirty laundry was theirs to clean.

During drives to Vermont my father would continue his stories. In his version of the Arthurian legends, few of the knights had children, but he did reveal that Lancelot had a son, whose name, he said, was Galahad. How Lancelot had raised a son while serving his king was a mystery to me, but my father assured me that Galahad was the purest and most righteous of any knight at the Round Table. It was Galahad, after all, who, before ascending to heaven, had been the only knight virtuous enough to behold the Holy Grail.

Whats a Holy Grail? I asked my father.

He nodded solemnly, then held his hands before him as if supporting an invisible ball. Its a big cup. A cup of God.

A cup of God. What color is the cup?

My father paused. Gold.

Yes, I thought. Of course. I looked out my window, at the rolling contours of the Green Mountains scrolling along the highway, until I saw him: a young white knight with a sword at his hip, rising through the clouds in a beam of light, bearing the golden Grail skyward like a sports trophy.

Later, toward nightfall, as we followed Route 2 past hazy glimpses of Lake Champlain, past the swamps and apple orchards and cedar forests of my former life, I felt the silent spell of destiny moving through me. As we turned onto the long gravel driveway, the windows of the old farmhouse glowed with soft candlelight, and the tilting barns rose above fields of cow corn like the walls of a fortress. To be free from the sleepy shadow of my dark-haired mother filled me with a magical sense of power; to be on my own, under the care of my father, told me that manhood was not far off. I knew nothing of what deeper emotions were at work inside me; nothing of the past that would curse my fathers love; nothing of how complicated love could become when woven through a loom of race, culture, and war. Then, I believed only in the truth of what lay before me: that the willow trees bowing to my arrival were the sentinels of my fathers kingdom.