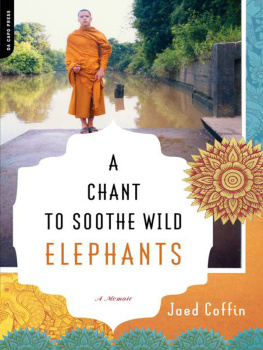

A

Chant

to Soothe

Wild Elephants

A

Chant

to Soothe

Wild Elephants

A Memoir

Jaed Coffin

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Da Capo Press was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters.

Copyright 2008 by Jaed Coffin

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Set in 12-point Goudy by Eclipse Publishing Services

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2008

ISBN-10 0306815265

ISBN-13 9780306815263

eBOOK ISBN: 9780306817311

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 911 10 09 08

For Koondtha and Koonmae

A Chant to Soothe Wild Elephants

Author unknown, Anthology of Asean Literatures, Volume IIa, ASEAN 1979 Translated and adapted from the original Thai by Panee Muncharoen and Jaed Coffin

12

Wild elephants, roped and captured for good purpose

You will be well raised and cared for.

13

May you feel no rage or sorrow Do not wail for your kin.

23

Do not long for sylvan bliss or lush green groves

Or the company of the wilderness.

24

Do not pine for the sweet scent of your mates

Or the fragrance of the nocturnal blossoms.

39

Walk on with resolution until you have come to the palace gates

And do not think to follow your footprints back into the forest.

54

Through the palace flow streams where you can bathe and play

There is red lotus and sweet young grass.

65

Wherever you walk there will be broad and even paths

Lined with coconut and sugar palm trees.

72

Give up your kicking, fighting, and thrashing about

Soothe your vicious temper.

74

Once you are dutiful and valiant in battle

You will be well fed and content.

76

Stirrups will hang from your neck, a rug will be draped over your back,

You will be glorious and graceful as you amble along.

A

Chant

to Soothe

Wild Elephants

Two Roots

W hen I was a boy, my mother used to bring my sister and me to Thailand every other year to visit our family in Panomsarakram, the village where she was born. From our home in Brunswick, Maine, it took us two full days to get there. Since my mother didnt want us to fall behind in school, we always traveled during our Christmas vacations. Along the way, we made stops in Alaska, China, Japan, and Taiwan, where my sister and I liked to wander the mysterious airports to marvel at the crowds of Asian people. When we arrived in Bangkok, I felt as if my world had been turned inside out. The snowy winter of Maine had been replaced by a heavy tropical heat.

Because of the twelve-hour time difference, I was sleepy during the day and awake at night. To my young mind, it just didnt seem possible that two such opposite places could exist on one planet.

Growing up, my mother didnt speak Thai to my sister and me at home, and while I was used to hearing the language and knew a handful of phrases, there was no one in Panomsarakram who I could really talk to. When people called us farang: foreigner, or look-krung: half-white child, I could only glare at them. But the village kids always came to our family housea simple wooden box with a tin roof, raised up on stiltsand invited us to do things that didnt require much talking. We swam naked in the brown water of the canal, made slingshots and climbed coconut trees, and played soccer barefoot with a straw da-graw ball on the red dirt fields of the temple grounds.

One of the first Thai words I learned was koondtha: grandfather. My koondtha was a medicine man. Since my grandmother had died when my mother was a teenager, Koondtha spent most of his time with the monks at the village temple, Wat Takwean, or in the forest, collecting plants for his ointments and medicines. Every morning I sat on the steps of our family house as Koondtha secured a tray of empty glass bottles onto a rack over the back wheel of his purple bicycle. I watched him ride off through the temple grounds, past the bodhi tree and along the canal, until his silhouette vanished into the bustle of the morning market on Panom Street.

When he returned in the late afternoon, the bottles were always full of roots and leaves, and bags of green oranges hung from both ends of his handlebars. Koondtha would park his bicycle, carry the bottles into the family house, and stack them on a high shelf. With a bag of oranges in each hand, hed take a seat next to me on the steps.

We had a system: Koondtha would hand me an orange slice and by the time Id eaten it and held the seeds between my teeth, hed be ready with another one. Id spit the seeds into the palm of his hand and take the next slice. We never said anything, but that didnt matter. I was happy to just eat oranges and contemplate my grandfathers curious features. I admired the wooden shine of his skin, his oiled silver hair, the musty smell of his collarless white shirts, and the thoughtful rhythm of his breathing.

Toward the end of the day, people would come to the steps to have Koondtha treat their wounds, broken bones, and fevers. Once, a young soldier in a military uniform arrived on a motorcycle, driving haphazardly with his right arm lying limp in his lap. He tried to stand and honor Koondtha with a customary wai, but his shoulder was in such pain that he could bring only one of his hands into prayer. I liked the seriousness of the soldiers well-fitted uniform and how the color of his sharply parted hair matched his polished black boots.

The soldier took off his shirt to show Koondtha his dislocated shoulder. The skin was deeply bruised purple and yellow, and was swollen to the height of his ear. Koondtha studied the injury as if it were the page of a book. He nodded to himself, selected a bottle of ointment from the shelf, and began rubbing the ointment onto the swelling. The young soldier gritted his teeth and started to sweat. He exhaled in short, quick breaths and tossed his head from side to side. His perfectly parted hair came undone and fell across his forehead.

Koondtha began chanting in low grumbling tones that I could barely hear. The prayers scared me, but I wanted to listen. As the soldier started crying, I watched the heel of his boot twist itself into the dirt. Koondtha lit what looked like a long cigar and held it under the soldiers armpit so that the smoke drifted into the bruised area. He spoke to the swelling as if telling it a secret. After several minutes, the soldier became calm. The muscles of his face relaxed, and he began to move his arm in ambitious circles. Without speaking, Koondtha capped the bottle of ointment and returned it to the shelf. When the soldier pressed his palms together to