To those who saw through the masquerades of tyranny and fought.

Foreword

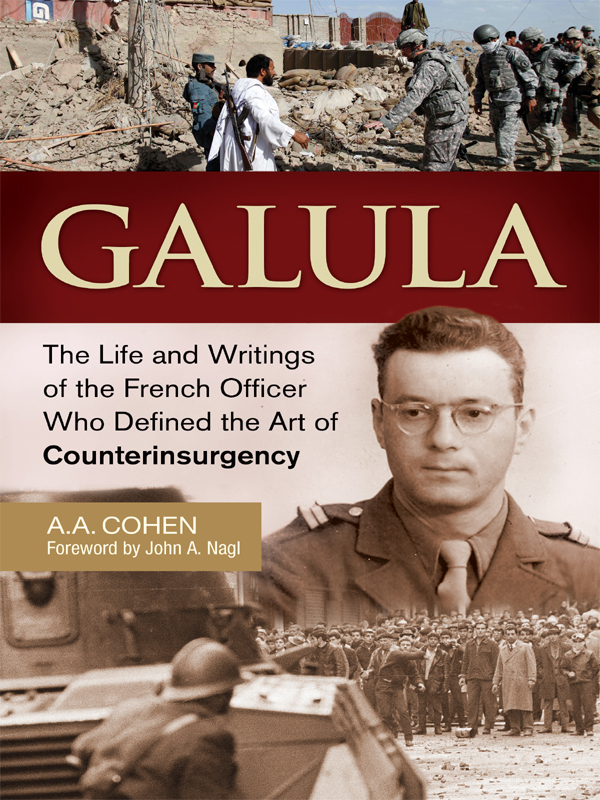

John A. Nagl

John A. Nagl is a retired U.S. Army officer who fought in both wars in Iraq and now teaches at the U.S. Naval Academy. He wrote the Foreword to a 2006 Praeger edition of Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice and, with General David Petraeus, to the first ever French translation of the same work in 2009.

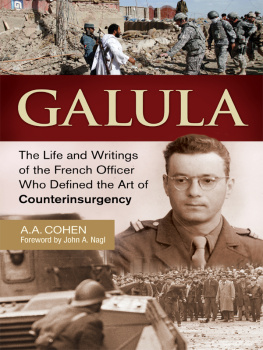

In the book of Mark, we learn that A prophet is honored everywhere except in his own hometown and among his relatives and his own family. Jesus of Nazareth could have added and in his own time to make the verse even more applicable, not just to himself, but also to Lieutenant Colonel David Galula. Galula was a French officer who did his most important fighting in Algeria, his most significant writing in the United States, and had the most influence he would ever enjoy forty years after his untimely demise in 1967. He was so without honor at home that his most important book, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, was not translated into his native French language until 2008. His ideas took more than forty years to make the voyage home, but when they did, they had been endorsed by American General David Petraeus and heavily influenced U.S. Army and Marine Corps counterinsurgency doctrine as well as the conduct of the two biggest wars of the early twenty-first century.

How this unlikely series of events came to pass is the story of this overdue biography, penned by Canadian Army Major A. A. Cohen. Like the subject of his work, Cohen is a young, bilingual army officer who benefits from both practical experience in the field and a passion for a series of ideas that can, and now have, changed the course of wars and of history. Cohens work benefits from the compassion of one soldier for another and from its author having lived, as his subject did, through a revolution in warfare.

David Galula cut his teeth on revolutionary war. Graduating from Saint Cyr just in time for the fall of France, he fought for the liberation of his country and then was posted to Beijing in time to observe Maos war of the people firsthand. Revolutions were sweeping the globe, populations empowered by new ideas were struggling to overthrow colonial overlords, and Galula saw governments both succeed and fail in attempts to suppress revolutions. He lived through popular uprisings and government attempts to subdue them in Greece, the Philippines, and French Indochina before being given the opportunity to put his learning to the test in Algeria in 1956. Assigned as a company commander with responsibility to pacify a sector, he developed, through trial and error, a system that worked.

Returning to Paris, Galula began lecturing and writing about his experiences in Algeria through the lens of nearly two decades of intensive study of revolutionary war. His ideas found purchase across the Atlantic Ocean, where the United States was struggling to understand the revolutions that were then reshaping Europe and Asia. Galula was encouraged by RANDs Steven Hosmer to write a major analysis of his combat experience, which was titled Pacification in Algeria, 19561958 when published (unfortunately in classified format) in 1963. It was not released to the general public until 2006, when a failing counterinsurgency campaign in Iraq made its lessons painfully relevant and a worthy introduction by Bruce Hoffman put them in context.

Pacification in Algeria is largely a substantial, historical text. It provided the grist from which an elegant and ultimately influential theoretical work was distilled. Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice was published in English in 1964, just as the United States was beginning to immerse itself into counterinsurgency warfare in Vietnam. Carl von Clausewitz observed that theory is most useful when it does not stray too far from the hard soil of practice. Galulas lessonsthat the object of counterinsurgency warfare is the population, that intelligence derived from that population is key to success in this most frustrating kind of war, that areas must be progressively cleared of enemy forces and then held in order to build a secure area that will remain loyal to the governmentwere intensely practical ones. They were also, sadly, not followed during the early years of Americas war in Vietnam. General William Westmoreland took a different path, one focused on searching for and destroying the enemy rather than on protecting the Vietnamese population. This ineffective and ultimately counterproductive strategy might have been avoided had Galula been more widely read, but it was not to be. He died in 1967, before the failings of American strategy in Vietnam became evident, and his ideas vanished beneath the wake of strategically failed counterinsurgency campaigns conducted by France and the United States. Both countries swore that they would never again engage in counterinsurgency, and Galulas ideas moldered on unvisited Staff College library shelves.